equity implications of health sector user fees in tanzania

equity implications of health sector user fees in tanzania

equity implications of health sector user fees in tanzania

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

VI IMPACT OF USER FEES IN TANZANIA<br />

6.1 User Fee charges<br />

Actual charges and proposed charges at PHC level<br />

It was difficult to obta<strong>in</strong> differentiated quantitative data on the actual <strong>user</strong> <strong>fees</strong> currently charged <strong>in</strong> the<br />

public and private <strong>sector</strong> (non-pr<strong>of</strong>it and for-pr<strong>of</strong>it) at <strong>health</strong> centre and dispensary level. Cost<strong>in</strong>g<br />

studies (HERA, 1999) reflect the actual costs <strong>of</strong> <strong>health</strong> services at <strong>health</strong> centre and dispensary level<br />

and relate this to the required <strong>in</strong>come for <strong>health</strong> facilities at PHC level, but do not <strong>in</strong>dicate the actual<br />

<strong>fees</strong> charged. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to MOH representatives <strong>in</strong> Kagera Region, the PHC facilities are suggested<br />

to follow the formal <strong>user</strong> fee charges given for District hospitals.<br />

The Health and Education F<strong>in</strong>ancial Track<strong>in</strong>g Study (1999) found that non-governmental <strong>health</strong><br />

facilities <strong>in</strong> most cases charge higher <strong>user</strong> <strong>fees</strong> than government facilities. This was also confirmed <strong>in</strong><br />

Kagera Region (see Technical Paper Part 5). Information that is available on <strong>user</strong> charges <strong>in</strong> the<br />

public facilities never <strong>in</strong>cludes the additional costs that people have to <strong>in</strong>cur for transport, purchase <strong>of</strong><br />

drugs or items that are supposed to be free <strong>of</strong> charge, un<strong>of</strong>ficial <strong>fees</strong>, etc. Table 6.1 <strong>in</strong>dicates that<br />

people <strong>of</strong>ten have to <strong>in</strong>cur substantial extra costs on top <strong>of</strong> the formal <strong>user</strong> fee charges.<br />

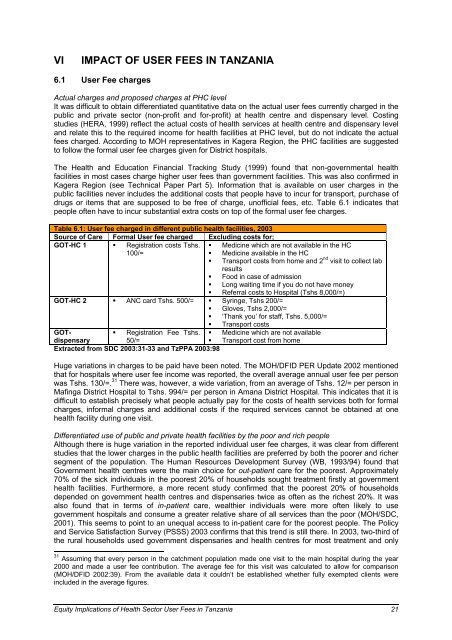

Table 6.1: User fee charged <strong>in</strong> different public <strong>health</strong> facilities, 2003<br />

Source <strong>of</strong> Care Formal User fee charged Exclud<strong>in</strong>g costs for;<br />

GOT-HC 1 � Registration costs Tshs. � Medic<strong>in</strong>e which are not available <strong>in</strong> the HC<br />

100/=<br />

�<br />

�<br />

Medic<strong>in</strong>e available <strong>in</strong> the HC<br />

Transport costs from home and 2 nd visit to collect lab<br />

results<br />

� Food <strong>in</strong> case <strong>of</strong> admission<br />

� Long wait<strong>in</strong>g time if you do not have money<br />

� Referral costs to Hospital (Tshs 8,000/=)<br />

GOT-HC 2 � ANC card Tshs. 500/= � Syr<strong>in</strong>ge, Tshs 200/=<br />

� Gloves, Tshs 2,000/=<br />

� ‘Thank you’ for staff, Tshs. 5,000/=<br />

� Transport costs<br />

GOT-<br />

� Registration Fee Tshs. � Medic<strong>in</strong>e which are not available<br />

dispensary<br />

50/=<br />

� Transport cost from home<br />

Extracted from SDC 2003:31-33 and TzPPA 2003:98<br />

Huge variations <strong>in</strong> charges to be paid have been noted. The MOH/DFID PER Update 2002 mentioned<br />

that for hospitals where <strong>user</strong> fee <strong>in</strong>come was reported, the overall average annual <strong>user</strong> fee per person<br />

was Tshs. 130/=. 31 There was, however, a wide variation, from an average <strong>of</strong> Tshs. 12/= per person <strong>in</strong><br />

Maf<strong>in</strong>ga District Hospital to Tshs. 994/= per person <strong>in</strong> Amana District Hospital. This <strong>in</strong>dicates that it is<br />

difficult to establish precisely what people actually pay for the costs <strong>of</strong> <strong>health</strong> services both for formal<br />

charges, <strong>in</strong>formal charges and additional costs if the required services cannot be obta<strong>in</strong>ed at one<br />

<strong>health</strong> facility dur<strong>in</strong>g one visit.<br />

Differentiated use <strong>of</strong> public and private <strong>health</strong> facilities by the poor and rich people<br />

Although there is huge variation <strong>in</strong> the reported <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>user</strong> fee charges, it was clear from different<br />

studies that the lower charges <strong>in</strong> the public <strong>health</strong> facilities are preferred by both the poorer and richer<br />

segment <strong>of</strong> the population. The Human Resources Development Survey (WB, 1993/94) found that<br />

Government <strong>health</strong> centres were the ma<strong>in</strong> choice for out-patient care for the poorest. Approximately<br />

70% <strong>of</strong> the sick <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong> the poorest 20% <strong>of</strong> households sought treatment firstly at government<br />

<strong>health</strong> facilities. Furthermore, a more recent study confirmed that the poorest 20% <strong>of</strong> households<br />

depended on government <strong>health</strong> centres and dispensaries twice as <strong>of</strong>ten as the richest 20%. It was<br />

also found that <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-patient care, wealthier <strong>in</strong>dividuals were more <strong>of</strong>ten likely to use<br />

government hospitals and consume a greater relative share <strong>of</strong> all services than the poor (MOH/SDC,<br />

2001). This seems to po<strong>in</strong>t to an unequal access to <strong>in</strong>-patient care for the poorest people. The Policy<br />

and Service Satisfaction Survey (PSSS) 2003 confirms that this trend is still there. In 2003, two-third <strong>of</strong><br />

the rural households used government dispensaries and <strong>health</strong> centres for most treatment and only<br />

31 Assum<strong>in</strong>g that every person <strong>in</strong> the catchment population made one visit to the ma<strong>in</strong> hospital dur<strong>in</strong>g the year<br />

2000 and made a <strong>user</strong> fee contribution. The average fee for this visit was calculated to allow for comparison<br />

(MOH/DFID 2002:39). From the available data it couldn’t be established whether fully exempted clients were<br />

<strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the average figures.<br />

Equity Implications <strong>of</strong> Health Sector User Fees <strong>in</strong> Tanzania 21