equity implications of health sector user fees in tanzania

equity implications of health sector user fees in tanzania

equity implications of health sector user fees in tanzania

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

An <strong>in</strong>dication <strong>of</strong> actual charges and additional costs to be paid by people <strong>in</strong> public PHC facilities is<br />

provided <strong>in</strong> Table 6.1. The table shows that the additional costs to be paid can be even 15 to 80 times<br />

more (or higher) than the formal fee implies! Poor people <strong>in</strong> a Lushoto <strong>health</strong> facility paid for an<br />

episode <strong>of</strong> illness on average 80% for drugs and other <strong>fees</strong>, 10% on transport, food and<br />

accommodation and 10% on <strong>in</strong>formal charges (Mamdami, 2003). In the PSSS, people expressed<br />

views on improvements and detoriation <strong>of</strong> costs and services. While 19% thought that the cost <strong>of</strong><br />

treatment had decl<strong>in</strong>ed, 39% thought it had <strong>in</strong>creased. While the availability <strong>of</strong> drugs <strong>in</strong>creased for<br />

nearly 30%, it deteriorated for 23% <strong>of</strong> the respondents (PSSS 2003:24-27, TzPPA 2003:97-98, SDC<br />

2003:31-33, Mamdami 2003:8-10; Msuya, 2003; Munga, 2003; Khan, 2003; Ewald et al, 2004).<br />

People’s ability to pay is not only determ<strong>in</strong>ed by treatment costs but also depends on <strong>in</strong>flexible<br />

payment modalities. Traditional healers are <strong>in</strong> that sense much more flexible than <strong>health</strong> facilities<br />

(Muela et al 2000:301). It has been estimated that <strong>in</strong> hospitals and dispensaries, 70% and 40% <strong>of</strong> the<br />

clients respectively, have difficulty to make the full payment for <strong>health</strong> services provided (Dercon<br />

2000:56).<br />

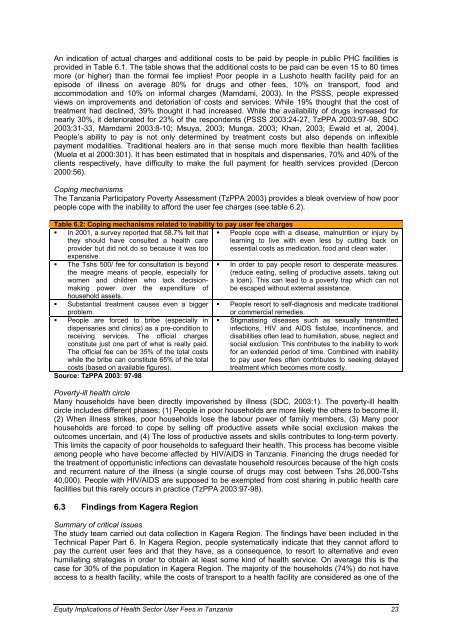

Cop<strong>in</strong>g mechanisms<br />

The Tanzania Participatory Poverty Assessment (TzPPA 2003) provides a bleak overview <strong>of</strong> how poor<br />

people cope with the <strong>in</strong>ability to afford the <strong>user</strong> fee charges (see table 6.2).<br />

Table 6.2: Cop<strong>in</strong>g mechanisms related to <strong>in</strong>ability to pay <strong>user</strong> fee charges<br />

� In 2001, a survey reported that 58.7% felt that<br />

they should have consulted a <strong>health</strong> care<br />

provider but did not do so because it was too<br />

expensive.<br />

� The Tshs 500/ fee for consultation is beyond<br />

the meagre means <strong>of</strong> people, especially for<br />

women and children who lack decisionmak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

power over the expenditure <strong>of</strong><br />

�<br />

household assets.<br />

Substantial treatment causes even a bigger<br />

problem.<br />

� People are forced to bribe (especially <strong>in</strong><br />

dispensaries and cl<strong>in</strong>ics) as a pre-condition to<br />

receiv<strong>in</strong>g services. The <strong>of</strong>ficial charges<br />

constitute just one part <strong>of</strong> what is really paid.<br />

The <strong>of</strong>ficial fee can be 35% <strong>of</strong> the total costs<br />

while the bribe can constitute 65% <strong>of</strong> the total<br />

costs (based on available figures).<br />

Source: TzPPA 2003: 97-98<br />

� People cope with a disease, malnutrition or <strong>in</strong>jury by<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g to live with even less by cutt<strong>in</strong>g back on<br />

essential costs as medication, food and clean water.<br />

� In order to pay people resort to desperate measures.<br />

(reduce eat<strong>in</strong>g, sell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> productive assets, tak<strong>in</strong>g out<br />

a loan). This can lead to a poverty trap which can not<br />

be escaped without external assistance.<br />

� People resort to self-diagnosis and medicate traditional<br />

or commercial remedies.<br />

� Stigmatis<strong>in</strong>g diseases such as sexually transmitted<br />

<strong>in</strong>fections, HIV and AIDS fistulae, <strong>in</strong>cont<strong>in</strong>ence, and<br />

disabilities <strong>of</strong>ten lead to humiliation, abuse, neglect and<br />

social exclusion. This contributes to the <strong>in</strong>ability to work<br />

for an extended period <strong>of</strong> time. Comb<strong>in</strong>ed with <strong>in</strong>ability<br />

to pay <strong>user</strong> <strong>fees</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten contributes to seek<strong>in</strong>g delayed<br />

treatment which becomes more costly.<br />

Poverty-ill <strong>health</strong> circle<br />

Many households have been directly impoverished by illness (SDC, 2003:1). The poverty-ill <strong>health</strong><br />

circle <strong>in</strong>cludes different phases; (1) People <strong>in</strong> poor households are more likely the others to become ill,<br />

(2) When illness strikes, poor households lose the labour power <strong>of</strong> family members, (3) Many poor<br />

households are forced to cope by sell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong>f productive assets while social exclusion makes the<br />

outcomes uncerta<strong>in</strong>, and (4) The loss <strong>of</strong> productive assets and skills contributes to long-term poverty.<br />

This limits the capacity <strong>of</strong> poor households to safeguard their <strong>health</strong>. This process has become visible<br />

among people who have become affected by HIV/AIDS <strong>in</strong> Tanzania. F<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g the drugs needed for<br />

the treatment <strong>of</strong> opportunistic <strong>in</strong>fections can devastate household resources because <strong>of</strong> the high costs<br />

and recurrent nature <strong>of</strong> the illness (a s<strong>in</strong>gle course <strong>of</strong> drugs may cost between Tshs 26,000-Tshs<br />

40,000). People with HIV/AIDS are supposed to be exempted from cost shar<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> public <strong>health</strong> care<br />

facilities but this rarely occurs <strong>in</strong> practice (TzPPA 2003:97-98).<br />

6.3 F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from Kagera Region<br />

Summary <strong>of</strong> critical issues<br />

The study team carried out data collection <strong>in</strong> Kagera Region. The f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs have been <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the<br />

Technical Paper Part 6. In Kagera Region, people systematically <strong>in</strong>dicate that they cannot afford to<br />

pay the current <strong>user</strong> <strong>fees</strong> and that they have, as a consequence, to resort to alternative and even<br />

humiliat<strong>in</strong>g strategies <strong>in</strong> order to obta<strong>in</strong> at least some k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> <strong>health</strong> service. On average this is the<br />

case for 30% <strong>of</strong> the population <strong>in</strong> Kagera Region. The majority <strong>of</strong> the households (74%) do not have<br />

access to a <strong>health</strong> facility, while the costs <strong>of</strong> transport to a <strong>health</strong> facility are considered as one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Equity Implications <strong>of</strong> Health Sector User Fees <strong>in</strong> Tanzania 23