George w. casey jr. - Federation of American Scientists

George w. casey jr. - Federation of American Scientists

George w. casey jr. - Federation of American Scientists

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Naqib. In fact, one recently released first-hand account<br />

from a former Taliban fighter refers to Naqib<br />

not as “general,” but as “mullah.” That is, the<br />

Taliban radically redefined battlefield force distribution<br />

by turning potential adversaries into allies. 7<br />

Moreover, while Naqib may have been the most<br />

powerful warlord that the Taliban co-opted, he<br />

certainly was not the only one. The Taliban developed<br />

numerous relationships with other Kandahar<br />

strongmen, including Keshkinakhud administrator<br />

Hajji Bashar and Argestan religious leader Mullah<br />

Rabbani Akhund. 8 Indeed, the decisive victory in<br />

Kandahar seems to have come–not on the battlefield–but<br />

during a meeting in Panjwayi, in which<br />

six Taliban leaders forged an informal agreement to<br />

coordinate efforts against the last remaining warlord,<br />

Ustaz Abdul Haleem.<br />

After the removal <strong>of</strong> Ustaz,<br />

the Taliban quickly gained<br />

control <strong>of</strong> the capital, with<br />

only a minimal number <strong>of</strong><br />

governor Gul Agha Sherzai’s<br />

troops resisting. 9<br />

The Taliban’s ability to mobilize<br />

previously existing political-military<br />

networks in<br />

order to alter battlefield dynamics<br />

highlights a broader<br />

trend in their campaign to<br />

control Afghanistan. Indeed,<br />

the Taliban established a<br />

unique set <strong>of</strong> tactics, techniques and procedures<br />

that differed significantly from the mujahedeen era<br />

hit-and-run tactics. Instead <strong>of</strong> relying on insurgent<br />

advantages in guerilla warfare, the Taliban adopted<br />

a dynamic, mobile, and aggressive operational<br />

tempo.<br />

While Taliban propaganda suggests that success<br />

in employing such tactics stemmed from the movement’s<br />

popular support and Taliban combatants’<br />

ideological zeal, Anthony Davis argues that Taliban<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>iciency in mobile warfare instead resulted from<br />

successfully integrating networks <strong>of</strong> former soldiers,<br />

who had been trained during the Soviet occupation<br />

in the employment <strong>of</strong> air, artillery, mortar and armor<br />

assets. The most notable <strong>of</strong> these networks was<br />

that <strong>of</strong> Defense Minister General Shahnawaz Tanai,<br />

who mobilized and persuaded former colleagues<br />

to assist in Taliban military operations. In fact,<br />

one source estimated that 1,600 <strong>of</strong>ficers from the<br />

People’s Democratic Party <strong>of</strong> Afghanistan (PDPA) regime<br />

were serving with the Taliban by 1995. 10<br />

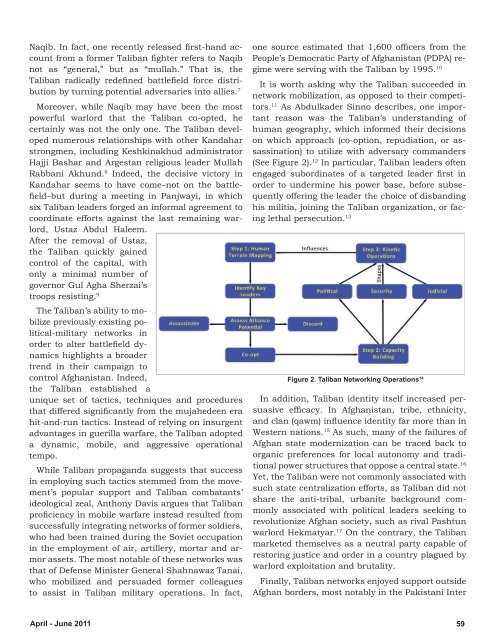

It is worth asking why the Taliban succeeded in<br />

network mobilization, as opposed to their competitors.<br />

11 As Abdulkader Sinno describes, one important<br />

reason was the Taliban’s understanding <strong>of</strong><br />

human geography, which informed their decisions<br />

on which approach (co-option, repudiation, or assassination)<br />

to utilize with adversary commanders<br />

(See Figure 2). 12 In particular, Taliban leaders <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

engaged subordinates <strong>of</strong> a targeted leader first in<br />

order to undermine his power base, before subsequently<br />

<strong>of</strong>fering the leader the choice <strong>of</strong> disbanding<br />

his militia, joining the Taliban organization, or facing<br />

lethal persecution. 13<br />

Figure 2. Taliban Networking Operations 14<br />

In addition, Taliban identity itself increased persuasive<br />

efficacy. In Afghanistan, tribe, ethnicity,<br />

and clan (qawm) influence identity far more than in<br />

Western nations. 15 As such, many <strong>of</strong> the failures <strong>of</strong><br />

Afghan state modernization can be traced back to<br />

organic preferences for local autonomy and traditional<br />

power structures that oppose a central state. 16<br />

Yet, the Taliban were not commonly associated with<br />

such state centralization efforts, as Taliban did not<br />

share the anti-tribal, urbanite background commonly<br />

associated with political leaders seeking to<br />

revolutionize Afghan society, such as rival Pashtun<br />

warlord Hekmatyar. 17 On the contrary, the Taliban<br />

marketed themselves as a neutral party capable <strong>of</strong><br />

restoring justice and order in a country plagued by<br />

warlord exploitation and brutality.<br />

Finally, Taliban networks enjoyed support outside<br />

Afghan borders, most notably in the Pakistani Inter<br />

April - June 2011 59