Analysis of Sales Promotion Effects on Household Purchase Behavior

Analysis of Sales Promotion Effects on Household Purchase Behavior

Analysis of Sales Promotion Effects on Household Purchase Behavior

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

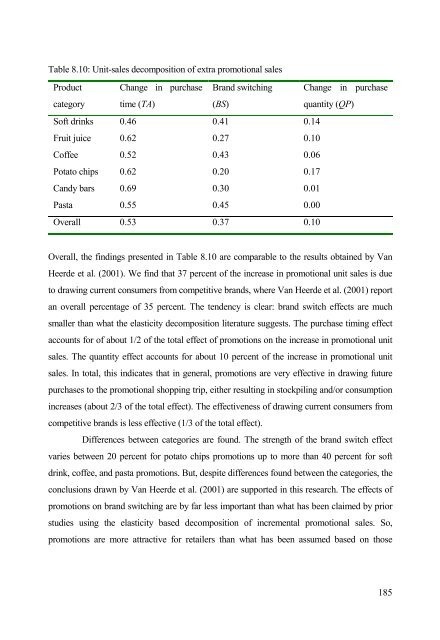

Table 8.10: Unit-sales decompositi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> extra promoti<strong>on</strong>al sales<br />

Product<br />

category<br />

Change in purchase<br />

time (TA)<br />

Brand switching<br />

(BS)<br />

S<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>t drinks 0.46 0.41 0.14<br />

Fruit juice 0.62 0.27 0.10<br />

C<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fee 0.52 0.43 0.06<br />

Potato chips 0.62 0.20 0.17<br />

Candy bars 0.69 0.30 0.01<br />

Pasta 0.55 0.45 0.00<br />

Overall 0.53 0.37 0.10<br />

Change in purchase<br />

quantity (QP)<br />

Overall, the findings presented in Table 8.10 are comparable to the results obtained by Van<br />

Heerde et al. (2001). We find that 37 percent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the increase in promoti<strong>on</strong>al unit sales is due<br />

to drawing current c<strong>on</strong>sumers from competitive brands, where Van Heerde et al. (2001) report<br />

an overall percentage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 35 percent. The tendency is clear: brand switch effects are much<br />

smaller than what the elasticity decompositi<strong>on</strong> literature suggests. The purchase timing effect<br />

accounts for <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> about 1/2 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the total effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> promoti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> the increase in promoti<strong>on</strong>al unit<br />

sales. The quantity effect accounts for about 10 percent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the increase in promoti<strong>on</strong>al unit<br />

sales. In total, this indicates that in general, promoti<strong>on</strong>s are very effective in drawing future<br />

purchases to the promoti<strong>on</strong>al shopping trip, either resulting in stockpiling and/or c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong><br />

increases (about 2/3 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the total effect). The effectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> drawing current c<strong>on</strong>sumers from<br />

competitive brands is less effective (1/3 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the total effect).<br />

Differences between categories are found. The strength <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the brand switch effect<br />

varies between 20 percent for potato chips promoti<strong>on</strong>s up to more than 40 percent for s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>t<br />

drink, c<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fee, and pasta promoti<strong>on</strong>s. But, despite differences found between the categories, the<br />

c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s drawn by Van Heerde et al. (2001) are supported in this research. The effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

promoti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> brand switching are by far less important than what has been claimed by prior<br />

studies using the elasticity based decompositi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> incremental promoti<strong>on</strong>al sales. So,<br />

promoti<strong>on</strong>s are more attractive for retailers than what has been assumed based <strong>on</strong> those<br />

185