stonehenge - English Heritage

stonehenge - English Heritage

stonehenge - English Heritage

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

047-120 section 2.qxd 6/21/05 4:18 PM Page 42<br />

Stonehenge Landscape (Illustration 24). Small-scale<br />

excavations in 1956 confirmed the identification of the<br />

earthworks as a causewayed enclosure of fourth-millennium<br />

BC date (Thomas 1964; Oswald et al. 2001, 157; McOmish et<br />

al. 2002, 31–5), but no more precise information about the<br />

chronology of the site is available. Morphologically, the site<br />

has two roughly concentric ditch circuits. The inner circuit is<br />

sub-circular, the outer circuit pentagonal in plan with the<br />

flat base to the southeast (Oswald et al. 2001, 5). The<br />

entrance in the inner circuit opens to the southeast. Surface<br />

evidence suggests complex patterns of ditch recutting and<br />

changes to the alignment of individual ditch segments.<br />

Despite the generally high level of aerial reconnaissance<br />

in the region, Robin Hood’s Ball seems to be a fairly isolated<br />

enclosure spatially associated with a relatively discrete<br />

cluster of long barrows and oval barrows fitting well with a<br />

dispersed pattern of middle Neolithic enclosures across<br />

central southern Britain (Ashbee 1984b, figure 6; Oswald et<br />

al. 2001, 80). This pattern was interpreted by Colin Renfrew<br />

(1973a, 549) in terms of emergent chiefdoms, with the long<br />

barrows representative of scattered local communities<br />

whose collective territorial focus was a causewayed<br />

enclosure (and cf. Ashbee 1978b, figure 22).<br />

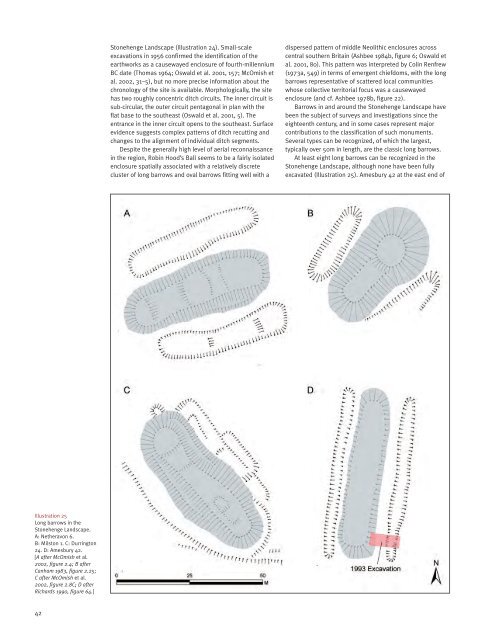

Barrows in and around the Stonehenge Landscape have<br />

been the subject of surveys and investigations since the<br />

eighteenth century, and in some cases represent major<br />

contributions to the classification of such monuments.<br />

Several types can be recognized, of which the largest,<br />

typically over 50m in length, are the classic long barrows.<br />

At least eight long barrows can be recognized in the<br />

Stonehenge Landscape, although none have been fully<br />

excavated (Illustration 25). Amesbury 42 at the east end of<br />

Illustration 25<br />

Long barrows in the<br />

Stonehenge Landscape.<br />

A: Netheravon 6.<br />

B: Milston 1. C: Durrington<br />

24. D: Amesbury 42.<br />

[A after McOmish et al.<br />

2002, figure 2.4; B after<br />

Canham 1983, figure 2.25;<br />

C after McOmish et al.<br />

2002, figure 2.8C; D after<br />

Richards 1990, figure 64.]<br />

42