A Basic Course in Anthropological Linguistics (Studies in Linguistic ...

A Basic Course in Anthropological Linguistics (Studies in Linguistic ...

A Basic Course in Anthropological Linguistics (Studies in Linguistic ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

78 A BASIC COURSE IN ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS<br />

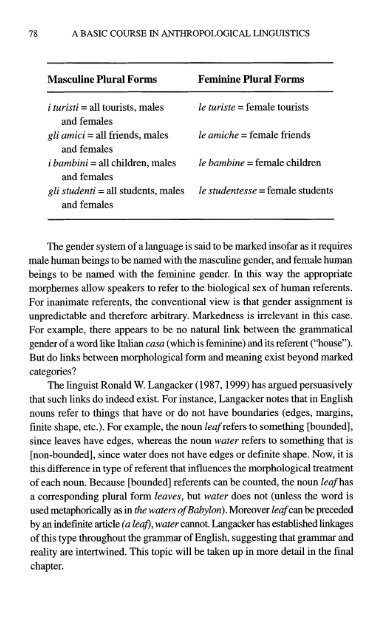

Mascul<strong>in</strong>e Plural Forms Fem<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e Plural Forms<br />

i turisti = all tourists, males<br />

and females<br />

gli amici = all friends, males<br />

and females<br />

i bamb<strong>in</strong>i = all children, males<br />

and females<br />

gli studenti = all students, males<br />

and females<br />

le turiste = female tourists<br />

le amiche = female friends<br />

le bamb<strong>in</strong>e = female children<br />

le studentesse = female students<br />

The gender system of a language is said to be marked <strong>in</strong>sofar as it requires<br />

male human be<strong>in</strong>gs to be named with the mascul<strong>in</strong>e gender, and female human<br />

be<strong>in</strong>gs to be named with the fem<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e gender. In this way the appropriate<br />

morphemes allow speakers to refer to the biological sex of human referents.<br />

For <strong>in</strong>animate referents, the conventional view is that gender assignment is<br />

unpredictable and therefore arbitrary. Markedness is irrelevant <strong>in</strong> this case.<br />

For example, there appears to be no natural l<strong>in</strong>k between the grammatical<br />

gender of a word like Italian casa (which is fem<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e) and its referent (“house”).<br />

But do l<strong>in</strong>ks between morphological form and mean<strong>in</strong>g exist beyond marked<br />

categories?<br />

The l<strong>in</strong>guist Ronald W. Langacker (1987,1999) has argued persuasively<br />

that such l<strong>in</strong>ks do <strong>in</strong>deed exist. For <strong>in</strong>stance, Langacker notes that <strong>in</strong> English<br />

nouns refer to th<strong>in</strong>gs that have or do not have boundaries (edges, marg<strong>in</strong>s,<br />

f<strong>in</strong>ite shape, etc.). For example, the noun leafrefers to someth<strong>in</strong>g [bounded],<br />

s<strong>in</strong>ce leaves have edges, whereas the noun water refers to someth<strong>in</strong>g that is<br />

[non-bounded], s<strong>in</strong>ce water does not have edges or def<strong>in</strong>ite shape. Now, it is<br />

this difference <strong>in</strong> type of referent that <strong>in</strong>fluences the morphological treatment<br />

of each noun. Because [bounded] referents can be counted, the noun leafhas<br />

a correspond<strong>in</strong>g plural form leaves, but water does not (unless the word is<br />

used metaphorically as <strong>in</strong> the waters of Babylon). Moreover leafcan be preceded<br />

by an <strong>in</strong>def<strong>in</strong>ite article (a leafl, water cannot. Langacker has established l<strong>in</strong>kages<br />

of ths type throughout the grammar of English, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that grammar and<br />

reality are <strong>in</strong>tertw<strong>in</strong>ed. This topic will be taken up <strong>in</strong> more detail <strong>in</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>al<br />

chapter.