- Page 2 and 3:

780.9 N532 v.2 5^5385 780.9 1532 T2

- Page 7 and 8:

NEW OXFORD HISTORY OF MUSIC VOLUME

- Page 10 and 11:

SACRED AND PROFANE MUSIC (St. John'

- Page 12 and 13:

Oxford University Press, Amen House

- Page 14 and 15:

vi GENERAL INTRODUCTION music is no

- Page 17 and 18:

CONTENTS GENERAL INTRODUCTION V INT

- Page 19 and 20:

CONTENTS xi The Easter Sepulchre Dr

- Page 21:

ILLUSTRATIONS SACRED AND PROFANE MU

- Page 24 and 25:

xvi INTRODUCTION TO VOLUME II indee

- Page 26 and 27:

xviii INTRODUCTION TO VOLUME II Cor

- Page 28 and 29:

2 EARLY CHRISTIAN MUSIC so that the

- Page 30 and 31:

4 EARLY CHRISTIAN MUSIC c. 430); bu

- Page 32 and 33:

6 EARLY CHRISTIAN MUSIC liturgical

- Page 34 and 35:

8 EARLY CHRISTIAN MUSIC (Assyrians)

- Page 36 and 37:

10 EARLY CHRISTIAN MUSIC The Syriac

- Page 38 and 39:

12 EARLY CHRISTIAN MUSIC hymns were

- Page 40 and 41:

II (a) MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHE

- Page 42 and 43:

16 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES th

- Page 44 and 45:

18 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES st

- Page 46 and 47:

20 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES Ch

- Page 48 and 49:

22 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES ro

- Page 50 and 51:

24 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES mo

- Page 52 and 53:

26 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES (M

- Page 54 and 55:

28 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES Th

- Page 56 and 57:

30 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES tw

- Page 58 and 59:

32 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES O)

- Page 60 and 61:

34 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES We

- Page 62 and 63:

36 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES Ow

- Page 64 and 65:

38 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES Th

- Page 66 and 67:

40 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES Th

- Page 68 and 69:

42 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES Mo

- Page 70 and 71:

44 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES of

- Page 72 and 73:

46 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES Mo

- Page 74 and 75:

48 MUSIC OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES we

- Page 77 and 78:

ETHIOPIAN MUSIC 49 tion where they

- Page 79 and 80:

ARMENIAN MUSIC 51 Armenian liturgy

- Page 81:

AN ARMENIAN HYMN BOOK WITH NEUMS Wr

- Page 84 and 85:

54 RUSSIAN CHANT it is therefore im

- Page 87 and 88:

DEVELOPMENT AND DECLINE 55 them the

- Page 89 and 90:

MANNER OF PERFORMANCE MANNER OF PER

- Page 91 and 92:

EARLIEST TRACES 59 used to pray and

- Page 93 and 94:

AMBROSIAN CHANT 61 other hand, Pete

- Page 95 and 96:

AMBROSIAN CHANT 63 contains the par

- Page 97 and 98:

; AMBROSIAN CHANT /Con-fi-te mUni D

- Page 99 and 100:

Ex. 17 (b) Antiphon AMBROSIAN CHANT

- Page 101 and 102:

AMBROSIAN CHANT 69 Lae- tis ca-na-m

- Page 103 and 104:

AMBROSIAN CHANT 71 antiphon, Sunol

- Page 105 and 106:

GALLICAN CHANT 73 was divided, litu

- Page 107 and 108:

GALLICAN CHANT 75 serving as a star

- Page 109 and 110:

GALLICAN CHANT 77 phons, which were

- Page 111 and 112:

GALLICAN CHANT 79 10. Antiphon of t

- Page 113 and 114:

GALLICAN CHANT 81 with the oriental

- Page 115 and 116:

MOZARABIC CHANT 83 (Our Father, who

- Page 117 and 118:

E Ex. 31 (b) MOZARABIC CHANT 85 te

- Page 119 and 120:

MOZARABIC CHANT 87 parce', &c.). Th

- Page 121 and 122:

Dei unigenitum, et ex Patre natum E

- Page 123 and 124:

MOZARABIC CHANT 91 to its close rel

- Page 125 and 126:

MUSICAL VALUE AND PRINCIPAL FEATURE

- Page 127 and 128:

FORMATION OF ROMAN LITURGICAL CHANT

- Page 129 and 130:

PERFECTION OF GREGORIAN CHANT 97 ve

- Page 131 and 132:

PERFECTION OF GREGORIAN CHANT 99 to

- Page 133 and 134:

DIFFUSION AND DECAY 101 its metrica

- Page 135 and 136:

MODERN RESTORATION 103 chief work o

- Page 137 and 138:

MODERN RESTORATION 105 of the Gradu

- Page 139 and 140:

SOURCES AND NOTATION 107 read, a si

- Page 142 and 143:

FAMILIES OF NEUMATIC NOTATIONS 1. N

- Page 144 and 145:

110 GREGORIAN CHANT as the forerunn

- Page 146 and 147:

112 GREGORIAN CHANT Final Range Dom

- Page 148 and 149:

114 GREGORIAN CHANT artistic resour

- Page 150 and 151:

116 GREGORIAN CHANT occurs it is de

- Page 152 and 153:

118 GREGORIAN CHANT o su - os, no l

- Page 154 and 155:

120 GREGORIAN CHANT florid, retains

- Page 156 and 157:

122 GREGORIAN CHANT r, %. a , me -

- Page 158 and 159:

124 GREGORIAN CHANT jubilus, or flo

- Page 160 and 161:

126 GREGORIAN CHANT etbe-ne-di- ctu

- Page 162 and 163:

V TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS TE

- Page 164 and 165:

130 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 166 and 167:

132 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 168 and 169:

134 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 170 and 171:

136 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 172 and 173:

138 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 174 and 175:

140 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 176 and 177:

142 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 178 and 179:

Ex. 47 contd. (Repetendd? et im - p

- Page 180 and 181:

146 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 182 and 183:

148 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 184 and 185:

150 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 186 and 187:

152 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 188 and 189:

154 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 190 and 191:

156 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 192 and 193:

158 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 194 and 195:

160 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 196 and 197:

162 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 198 and 199:

or nos di - nes sup-plan te tuser-

- Page 200 and 201:

166 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 202 and 203:

168 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 204 and 205:

170 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 206 and 207:

172 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 208 and 209:

174 TROPE, SEQUENCE, AND CONDUCTUS

- Page 210 and 211:

176 LITURGICAL DRAMA twenty-two exa

- Page 212 and 213:

178 LITURGICAL DRAMA From the two o

- Page 215 and 216:

vr**- THE EASTER SEPULCHRE DRAMA 17

- Page 217 and 218:

Ci- to e - un - -re-xit Do -mi - nu

- Page 219 and 220:

a note. The first part is lyrical T

- Page 221 and 222:

THE EASTER SEPULCHRE DRAMA 185 and

- Page 223 and 224:

Ex. 64 CO) UuT THE EASTER SEPULCHRE

- Page 225 and 226:

THE EASTER SEPULCHRE DRAMA 189 the

- Page 227 and 228:

Ex. 65 a) 6- e a V. PEREGRINUS PLAY

- Page 229 and 230:

PEREGR1NUS PLAYS 193 incredulity an

- Page 231 and 232:

PASSION PLAYS 195 in metrical form,

- Page 233 and 234:

CHRISTMAS PLAYS 197 manger, a tradi

- Page 235 and 236:

CHRISTMAS PLAYS 199 other extant Of

- Page 237 and 238:

CHRISTMAS PLAYS 201 Finally the Off

- Page 239 and 240:

CHRISTMAS PLAYS 203 main altar to t

- Page 241 and 242:

CHRISTMAS PLAYS 205 so long and unw

- Page 243 and 244:

SUNDRY RELIGIOUS PLAYS 207 Abelard,

- Page 245 and 246:

SUNDRY RELIGIOUS PLAYS 209 (Let us,

- Page 247 and 248:

SUNDRY RELIGIOUS PLAYS 211 these st

- Page 249 and 250:

Ex. 77 &0 ^ ^3F SUNDRY RELIGIOUS PL

- Page 251 and 252:

THE DANIEL PLAYS 215 or Darius, is

- Page 253 and 254:

THE DANIEL PLAYS 217 returns wholly

- Page 255 and 256:

Ex. 85 CO &- Et.8 5 (ii) THE DANIEL

- Page 258 and 259:

4|4rri "'" ift.'i. 1 Lfe'' ,'^iiiC,

- Page 260 and 261:

222 MEDIEVAL SONG express moral sen

- Page 262 and 263:

224 MEDIEVAL SONG narrative alterna

- Page 264 and 265:

226 MEDIEVAL SONG that the music is

- Page 266 and 267:

228 MEDIEVAL SONG and perfect notes

- Page 268 and 269:

230 MEDIEVAL SONG *J fliJ ^ son. Oi

- Page 270 and 271:

232 MEDIEVAL SONG (All my desire an

- Page 272 and 273:

234 MEDIEVAL SONG (la the year when

- Page 274 and 275:

236 MEDIEVAL SONG m i ^ Et la gen -

- Page 276 and 277:

238 Ex. roc 1 (PEDES) MEDIEVAL SONG

- Page 278 and 279:

(If by the power of mercy true love

- Page 280 and 281:

242 MEDIEVAL SONG E - y - a, 'E pir

- Page 282 and 283:

244 MEDIEVAL SONG (Clap your hands,

- Page 284 and 285:

246 MEDIEVAL SONG -a - mou-rat. Que

- Page 286 and 287:

248 MEDIEVAL SONG so good to hear a

- Page 288 and 289:

250 MEDIEVAL SONG that the Middle A

- Page 290 and 291:

252 MEDIEVAL SONG (The world's joy

- Page 292 and 293:

254 MEDIEVAL SONG dich be - hu - te

- Page 294 and 295:

256 MEDIEVAL SONG was ghe - stalt.

- Page 296 and 297:

258 MEDIEVAL SONG Ex. uo l Ey ichsa

- Page 298 and 299:

260 MEDIEVAL SONG structure by the

- Page 300 and 301:

262 EX. I2Q 1 J-. Ji J' J MEDIEVAL

- Page 302 and 303:

MEDIEVAL SONG Et du - rou as - si c

- Page 304 and 305:

266 MEDIEVAL SONG The tritone (F to

- Page 306 and 307:

268 MEDIEVAL SONG Ex.135 1 di - m -

- Page 308 and 309:

VIII THE BIRTH OF POLYPHONY By DOM

- Page 310 and 311:

272 THE BIRTH OF POLYPHONY prosody

- Page 312 and 313:

274 THE BIRTH OF POLYPHONY some of

- Page 314 and 315:

276 THE BIRTH OF POLYPHONY cymbals

- Page 316 and 317:

278 THE BIRTH OF POLYPHONY works ma

- Page 318 and 319:

280 THE BIRTH OF POLYPHONY occurred

- Page 320 and 321:

282 THE BIRTH OF POLYPHONY entire c

- Page 322 and 323:

284 THE BIRTH OF POLYPHONY 'i n i i

- Page 324 and 325:

286 THE BIRTH OF POLYPHONY instruct

- Page 326 and 327:

288 MUSIC IN THE TWELFTH CENTURY of

- Page 328 and 329:

290 MUSIC IN THE TWELFTH CENTURY gi

- Page 330 and 331:

292 MUSIC IN THE TWELFTH CENTURY Ne

- Page 332 and 333:

294 MUSIC IN THE TWELFTH CENTURY It

- Page 334 and 335:

296 MUSIC IN THE TWELFTH CENTURY TH

- Page 336 and 337:

298 MUSIC IN THE TWELFTH CENTURY th

- Page 338 and 339:

MUSIC IN THE TWELFTH CENTURY Rex im

- Page 340:

302 MUSIC IN THE TWELFTH CENTURY pa

- Page 343 and 344:

THREE-PART WRITING 303 Patrishumana

- Page 345 and 346:

THREE-PART WRITING 305 with six thi

- Page 347 and 348:

THREE-PART WRITING 307 One short ex

- Page 349 and 350:

*UT TUO PROPITIATUS pec - ca - tis

- Page 351 and 352:

X MUSIC IN FIXED RHYTHM By DOM ANSE

- Page 353 and 354:

PRELIMINARY REMARKS ON DATES AND DA

- Page 355 and 356:

THE GENERAL PICTURE 315 from which

- Page 357 and 358:

THE GENERAL PICTURE 317 key'. 1 Els

- Page 359 and 360:

THE RHYTHMIC MODES 319 are based fa

- Page 361 and 362: THE RHYTHMIC MODES 321 The lower vo

- Page 363 and 364: THE RHYTHMIC MODES 323 values were

- Page 365 and 366: THE RHYTHMIC MODES 325 The falling

- Page 367 and 368: THE CONDUCTUS 327 appears at the en

- Page 369 and 370: THE CONDUCTUS 329 reality. The same

- Page 371 and 372: Tort contd. THE CONDUCTUS 331

- Page 373 and 374: THE CONDUCTUS 333 (Under the type o

- Page 375 and 376: THE CONDUCTUS 335 Another tune, whe

- Page 377 and 378: DANCE MUSIC THE CONDUCTUS There are

- Page 379 and 380: DANCE MUSIC 339 Its position in the

- Page 381 and 382: THE RELATIONSHIP OF THE INDIVIDUAL

- Page 383 and 384: ^ EARLY ENGLISH PART-SONGS s Je flo

- Page 385 and 386: ORGANUM The appoggiatura formation

- Page 387 and 388: ORGANUM 347 Perotin comes from Anon

- Page 389 and 390: CLAUSULAE 349 also combinations of

- Page 391 and 392: 'ENGLISH DESCANT* 351 years no conf

- Page 393 and 394: XI THE MOTET AND ALLIED FORMS By DO

- Page 395 and 396: GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS 355 an inst

- Page 397 and 398: THE ORIGINAL STRUCTURE OF THE MOTET

- Page 399 and 400: TENOR THEMES 359 tions of the Grego

- Page 401 and 402: 'MANERE' the Gradual for the feast,

- Page 403 and 404: 'MANERE' 363 From the verse of the

- Page 405 and 406: 'MANERE' 365 The tenor melody is re

- Page 407 and 408: -ri - a, ma-ter pi - a, stel - la m

- Page 409 and 410: NOTATION 369 diamond shape for the

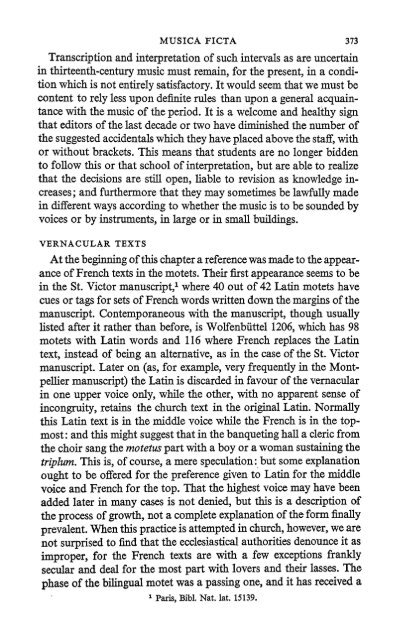

- Page 411: MUSICA FICTA 371 scientific, and in

- Page 415 and 416: INTERCHANGE AND IMITATION 375 - am.

- Page 417 and 418: INTERCHANGE AND IMITATION gnificat]

- Page 419 and 420: LATER ARS ANTIQUA 379 evolving the

- Page 421 and 422: MENSURAL NOTATION 381 tempus (later

- Page 423 and 424: MENSURAL NOTATION 383 four or more

- Page 425 and 426: TECHNICAL DEVELOPMENTS 385 ( x ) Te

- Page 427 and 428: TECHNICAL DEVELOPMENTS 387 while th

- Page 429 and 430: A doubt has been cast 1 HARMONY 389

- Page 431 and 432: 5-F In MS. ISORHYTHM 391 32 ^ m -bi

- Page 433 and 434: Ex. 216 Veritatem ISORHYTHM 393 s ^

- Page 435 and 436: ISORHYTHM 395 (Triplum: O Mary, vir

- Page 437 and 438: ENGLISH MOTETS FOR FOUR VOICES * D

- Page 439 and 440: HOCKET in va - cu- m is al-mis pre

- Page 441 and 442: DUPLE TIME 401 val of nearly fifty

- Page 443 and 444: 'SUMER IS ICUMEN IN' 403 it is also

- Page 445 and 446: BIBLIOGRAPHY GENERAL ADLER, GUIDO:

- Page 447 and 448: BIBLIOGRAPHY 407 KIRCHHOFF, K.: Die

- Page 449 and 450: BIBLIOGRAPHY PaUographie musicale,

- Page 451 and 452: BIBLIOGRAPHY 411 MOBERG, C. A, : Vb

- Page 453 and 454: (ii) Books and Articles BIBLIOGRAPH

- Page 455 and 456: SOWA, HEINRICH: TextvariationenzurM

- Page 457 and 458: BIBLIOGRAPHY 417 WOLF, JOHANNES: 'D

- Page 459 and 460: Aristotle, 325, 372. Aries, 73, 74.

- Page 461 and 462: Contakion, see Kontakion. Contrary

- Page 463 and 464:

Gnostics, 8. Godric, St., 251. Goli

- Page 465 and 466:

Leo the Great, Pope, 95, 119. Leo I

- Page 467 and 468:

Rome, Vatican Libr., Archives of St

- Page 469 and 470:

Pitch, 287, 293. Plainsong, 105. Ru

- Page 471 and 472:

Reinach, T., 5 nl . Reinmar von Zwe

- Page 473 and 474:

Timocles, 19. Tintern, 314. Tischle

- Page 475:

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN AT THE UNI