their - The University of Texas at Dallas

their - The University of Texas at Dallas

their - The University of Texas at Dallas

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

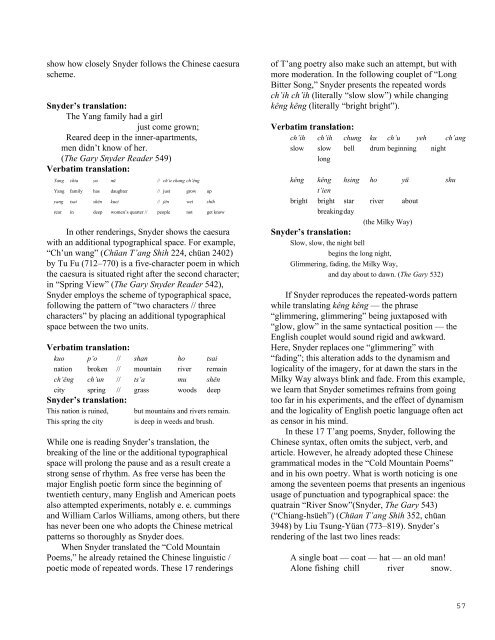

show how closely Snyder follows the Chinese caesura<br />

scheme.<br />

Snyder’s transl<strong>at</strong>ion:<br />

<strong>The</strong> Yang family had a girl<br />

just come grown;<br />

Reared deep in the inner-apartments,<br />

men didn’t know <strong>of</strong> her.<br />

(<strong>The</strong> Gary Snyder Reader 549)<br />

Verb<strong>at</strong>im transl<strong>at</strong>ion:<br />

Yang chia yu nü // ch’u chang ch’êng<br />

Yang family has daughter // just grow up<br />

yang tsai shên kuei // jên wei shih<br />

rear in deep women’s quarter // people not get know<br />

In other renderings, Snyder shows the caesura<br />

with an additional typographical space. For example,<br />

“Ch’un wang” (Chüan T’ang Shih 224, chüan 2402)<br />

by Tu Fu (712–770) is a five-character poem in which<br />

the caesura is situ<strong>at</strong>ed right after the second character;<br />

in “Spring View” (<strong>The</strong> Gary Snyder Reader 542),<br />

Snyder employs the scheme <strong>of</strong> typographical space,<br />

following the p<strong>at</strong>tern <strong>of</strong> “two characters // three<br />

characters” by placing an additional typographical<br />

space between the two units.<br />

Verb<strong>at</strong>im transl<strong>at</strong>ion:<br />

kuo p’o // shan ho tsai<br />

n<strong>at</strong>ion broken // mountain river remain<br />

ch’êng ch’un // ts’a mu shên<br />

city spring // grass woods deep<br />

Snyder’s transl<strong>at</strong>ion:<br />

This n<strong>at</strong>ion is ruined, but mountains and rivers remain.<br />

This spring the city is deep in weeds and brush.<br />

While one is reading Snyder’s transl<strong>at</strong>ion, the<br />

breaking <strong>of</strong> the line or the additional typographical<br />

space will prolong the pause and as a result cre<strong>at</strong>e a<br />

strong sense <strong>of</strong> rhythm. As free verse has been the<br />

major English poetic form since the beginning <strong>of</strong><br />

twentieth century, many English and American poets<br />

also <strong>at</strong>tempted experiments, notably e. e. cummings<br />

and William Carlos Williams, among others, but there<br />

has never been one who adopts the Chinese metrical<br />

p<strong>at</strong>terns so thoroughly as Snyder does.<br />

When Snyder transl<strong>at</strong>ed the “Cold Mountain<br />

Poems,” he already retained the Chinese linguistic /<br />

poetic mode <strong>of</strong> repe<strong>at</strong>ed words. <strong>The</strong>se 17 renderings<br />

<strong>of</strong> T’ang poetry also make such an <strong>at</strong>tempt, but with<br />

more moder<strong>at</strong>ion. In the following couplet <strong>of</strong> “Long<br />

Bitter Song,” Snyder presents the repe<strong>at</strong>ed words<br />

ch’ih ch’ih (literally “slow slow”) while changing<br />

kêng kêng (literally “bright bright”).<br />

Verb<strong>at</strong>im transl<strong>at</strong>ion:<br />

ch’ih ch’ih chung ku ch’u yeh ch’ang<br />

slow slow bell drum beginning night<br />

long<br />

kêng kêng hsing ho yü shu<br />

t’ien<br />

bright bright star river about<br />

breaking day<br />

(the Milky Way)<br />

Snyder’s transl<strong>at</strong>ion:<br />

Slow, slow, the night bell<br />

begins the long night,<br />

Glimmering, fading, the Milky Way,<br />

and day about to dawn. (<strong>The</strong> Gary 532)<br />

If Snyder reproduces the repe<strong>at</strong>ed-words p<strong>at</strong>tern<br />

while transl<strong>at</strong>ing kêng kêng — the phrase<br />

“glimmering, glimmering” being juxtaposed with<br />

“glow, glow” in the same syntactical position — the<br />

English couplet would sound rigid and awkward.<br />

Here, Snyder replaces one “glimmering” with<br />

“fading”; this alter<strong>at</strong>ion adds to the dynamism and<br />

logicality <strong>of</strong> the imagery, for <strong>at</strong> dawn the stars in the<br />

Milky Way always blink and fade. From this example,<br />

we learn th<strong>at</strong> Snyder sometimes refrains from going<br />

too far in his experiments, and the effect <strong>of</strong> dynamism<br />

and the logicality <strong>of</strong> English poetic language <strong>of</strong>ten act<br />

as censor in his mind.<br />

In these 17 T’ang poems, Snyder, following the<br />

Chinese syntax, <strong>of</strong>ten omits the subject, verb, and<br />

article. However, he already adopted these Chinese<br />

gramm<strong>at</strong>ical modes in the “Cold Mountain Poems”<br />

and in his own poetry. Wh<strong>at</strong> is worth noticing is one<br />

among the seventeen poems th<strong>at</strong> presents an ingenious<br />

usage <strong>of</strong> punctu<strong>at</strong>ion and typographical space: the<br />

qu<strong>at</strong>rain “River Snow”(Snyder, <strong>The</strong> Gary 543)<br />

(“Chiang-hsüeh”) (Chüan T’ang Shih 352, chüan<br />

3948) by Liu Tsung-Yüan (773–819). Snyder’s<br />

rendering <strong>of</strong> the last two lines reads:<br />

A single bo<strong>at</strong> — co<strong>at</strong> — h<strong>at</strong> — an old man!<br />

Alone fishing chill river snow.<br />

57