their - The University of Texas at Dallas

their - The University of Texas at Dallas

their - The University of Texas at Dallas

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Here, the word order accords well with th<strong>at</strong> in the<br />

original; in addition, Snyder so deftly employs<br />

punctu<strong>at</strong>ion and space th<strong>at</strong> the visual effect is<br />

stunning. <strong>The</strong> three consecutive dashes transform the<br />

“bo<strong>at</strong>,” the “co<strong>at</strong>,” the “h<strong>at</strong>” and the “old man” into<br />

four frames <strong>of</strong> imagery th<strong>at</strong> appear one after another<br />

in the reader’s vision. After the reader visualizes the<br />

bo<strong>at</strong>, then the co<strong>at</strong>, the h<strong>at</strong>, and eventually the image<br />

<strong>of</strong> the old man, the exclam<strong>at</strong>ion mark would bring a<br />

surprise to him: indeed, it is an old fisherman! In the<br />

second line, between every two words, there are three<br />

typographical spaces, which can draw the reader’s<br />

<strong>at</strong>tention to every single word. Snyder says, “<strong>The</strong><br />

placement <strong>of</strong> the line on the page, the horizontal white<br />

spaces and vertical white spaces are all scoring for<br />

how it is to be read and how it is to be timed” (<strong>The</strong><br />

Real Work 31). This spacing device would slow down<br />

the reading speed considerably; the reader’s focus will<br />

be placed on each word, cre<strong>at</strong>ing a mood <strong>of</strong> isol<strong>at</strong>ion.<br />

This is the only line to which Snyder applies such a<br />

spacing device; the aim is obvious: while the grand,<br />

panoramic landscape is depicted by the two images in<br />

the first two lines, “these thousand peaks” and “all the<br />

trails,” the “old man” line focuses one’s vision on a<br />

single spot in the vastness. As a result, the spacing<br />

device could strengthen the sense <strong>of</strong> desol<strong>at</strong>ion and<br />

the idea <strong>of</strong> the rel<strong>at</strong>ive insignificance <strong>of</strong> humans.<br />

In these transl<strong>at</strong>ions, Snyder adheres more to the<br />

formalistic aspects <strong>of</strong> classical Chinese poetry,<br />

whereas the “Cold Mountain Poems” pay less<br />

<strong>at</strong>tention to the rules and thus read more fluently.<br />

Snyder’s devi<strong>at</strong>ion in the second <strong>of</strong> the “Cold<br />

Mountain Poems” is renowned: “Go tell families with<br />

silverware and cars / ‘Wh<strong>at</strong>’s the use <strong>of</strong> all th<strong>at</strong> noise<br />

and money’” <strong>The</strong> couplet should be rendered: “go<br />

tell the family with bells and caldrons in its dining hall<br />

/ ‘Wh<strong>at</strong> is the use <strong>of</strong> vain fame’” Snyder’s<br />

contemporized version has become a showcase <strong>of</strong><br />

transl<strong>at</strong>ion. <strong>The</strong>re also appears to be a drastic<br />

departure from the rules in the T’ang transl<strong>at</strong>ions,<br />

although it is controversial: his interpret<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> a<br />

word in the “Deer Camp” written by Wang Wei (699–<br />

759) (Snyder, <strong>The</strong> Gary Snyder Reader 539). <strong>The</strong> last<br />

two lines <strong>of</strong> the original qu<strong>at</strong>rain “Lu ch’ai” (Chüan<br />

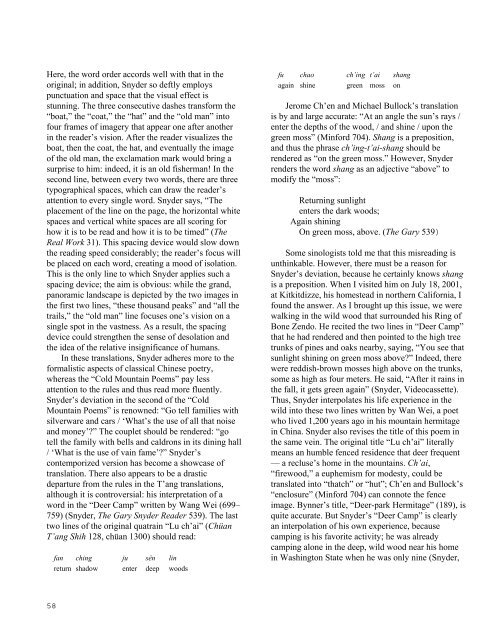

T’ang Shih 128, chüan 1300) should read:<br />

fan ching ju sên lin<br />

return shadow enter deep woods<br />

fu chao ch’ing t’ai shang<br />

again shine green moss on<br />

Jerome Ch’en and Michael Bullock’s transl<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

is by and large accur<strong>at</strong>e: “At an angle the sun’s rays /<br />

enter the depths <strong>of</strong> the wood, / and shine / upon the<br />

green moss” (Minford 704). Shang is a preposition,<br />

and thus the phrase ch’ing-t’ai-shang should be<br />

rendered as “on the green moss.” However, Snyder<br />

renders the word shang as an adjective “above” to<br />

modify the “moss”:<br />

Returning sunlight<br />

enters the dark woods;<br />

Again shining<br />

On green moss, above. (<strong>The</strong> Gary 539)<br />

Some sinologists told me th<strong>at</strong> this misreading is<br />

unthinkable. However, there must be a reason for<br />

Snyder’s devi<strong>at</strong>ion, because he certainly knows shang<br />

is a preposition. When I visited him on July 18, 2001,<br />

<strong>at</strong> Kitkitdizze, his homestead in northern California, I<br />

found the answer. As I brought up this issue, we were<br />

walking in the wild wood th<strong>at</strong> surrounded his Ring <strong>of</strong><br />

Bone Zendo. He recited the two lines in “Deer Camp”<br />

th<strong>at</strong> he had rendered and then pointed to the high tree<br />

trunks <strong>of</strong> pines and oaks nearby, saying, “You see th<strong>at</strong><br />

sunlight shining on green moss above” Indeed, there<br />

were reddish-brown mosses high above on the trunks,<br />

some as high as four meters. He said, “After it rains in<br />

the fall, it gets green again” (Snyder, Videocassette).<br />

Thus, Snyder interpol<strong>at</strong>es his life experience in the<br />

wild into these two lines written by Wan Wei, a poet<br />

who lived 1,200 years ago in his mountain hermitage<br />

in China. Snyder also revises the title <strong>of</strong> this poem in<br />

the same vein. <strong>The</strong> original title “Lu ch’ai” literally<br />

means an humble fenced residence th<strong>at</strong> deer frequent<br />

— a recluse’s home in the mountains. Ch’ai,<br />

“firewood,” a euphemism for modesty, could be<br />

transl<strong>at</strong>ed into “th<strong>at</strong>ch” or “hut”; Ch’en and Bullock’s<br />

“enclosure” (Minford 704) can connote the fence<br />

image. Bynner’s title, “Deer-park Hermitage” (189), is<br />

quite accur<strong>at</strong>e. But Snyder’s “Deer Camp” is clearly<br />

an interpol<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> his own experience, because<br />

camping is his favorite activity; he was already<br />

camping alone in the deep, wild wood near his home<br />

in Washington St<strong>at</strong>e when he was only nine (Snyder,<br />

58