Market Economics | Interest Rate Strategy - BNP PARIBAS ...

Market Economics | Interest Rate Strategy - BNP PARIBAS ...

Market Economics | Interest Rate Strategy - BNP PARIBAS ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

• Credibility. Spain’s record in terms of public<br />

finances is one of the strongest within the<br />

eurozone while Portugal has achieved significant<br />

adjustments in the past. Greece, with a record of<br />

having published incorrect figures on more than<br />

one occasion, has much less credibility; and<br />

• Last but not least, social tolerance. Portugal’s<br />

past adjustment has shown a high degree of<br />

social tolerance. The ability of Greek society to<br />

withstand the needed fiscal adjustment is one of<br />

the market’s primary reasons for concern.<br />

Yesterday’s tragic events were a harsh reminder<br />

of the difficulties lying ahead for the Greek<br />

government.<br />

That said, peripheral economies share a number of<br />

weaknesses that, in the absence of a quick and<br />

credible adjustment, make them vulnerable to further<br />

market tensions.<br />

More specifically, Portugal and Greece share a key<br />

feature: a lack of competitiveness associated with a<br />

low rate of national savings. This implies they rely on<br />

inflows of capital to finance consumption.<br />

Conversely, in Spain and Ireland, private debt and<br />

the state of the financial system are the core of the<br />

problem. Both economies are undergoing a<br />

significant adjustment in the housing sector which is<br />

heavily weighing on growth, with negative<br />

implications for the banking sector. Italy is in a group<br />

of its own. Both internal and external imbalances are<br />

less of an issue than for other peripheral economies<br />

but the high level of public debt is a persistent risk<br />

factor.<br />

Portugal<br />

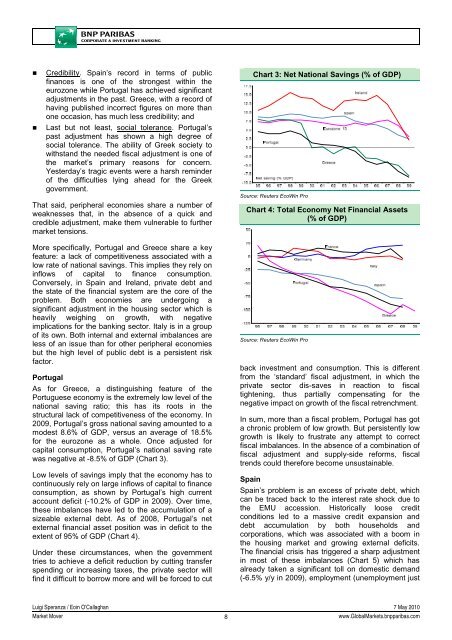

As for Greece, a distinguishing feature of the<br />

Portuguese economy is the extremely low level of the<br />

national saving ratio; this has its roots in the<br />

structural lack of competitiveness of the economy. In<br />

2009, Portugal’s gross national saving amounted to a<br />

modest 8.6% of GDP, versus an average of 18.5%<br />

for the eurozone as a whole. Once adjusted for<br />

capital consumption, Portugal’s national saving rate<br />

was negative at -8.5% of GDP (Chart 3).<br />

Low levels of savings imply that the economy has to<br />

continuously rely on large inflows of capital to finance<br />

consumption, as shown by Portugal’s high current<br />

account deficit (-10.2% of GDP in 2009). Over time,<br />

these imbalances have led to the accumulation of a<br />

sizeable external debt. As of 2008, Portugal’s net<br />

external financial asset position was in deficit to the<br />

extent of 95% of GDP (Chart 4).<br />

Under these circumstances, when the government<br />

tries to achieve a deficit reduction by cutting transfer<br />

spending or increasing taxes, the private sector will<br />

find it difficult to borrow more and will be forced to cut<br />

Chart 3: Net National Savings (% of GDP)<br />

Source: Reuters EcoWin Pro<br />

Chart 4: Total Economy Net Financial Assets<br />

(% of GDP)<br />

Source: Reuters EcoWin Pro<br />

back investment and consumption. This is different<br />

from the ‘standard’ fiscal adjustment, in which the<br />

private sector dis-saves in reaction to fiscal<br />

tightening, thus partially compensating for the<br />

negative impact on growth of the fiscal retrenchment.<br />

In sum, more than a fiscal problem, Portugal has got<br />

a chronic problem of low growth. But persistently low<br />

growth is likely to frustrate any attempt to correct<br />

fiscal imbalances. In the absence of a combination of<br />

fiscal adjustment and supply-side reforms, fiscal<br />

trends could therefore become unsustainable.<br />

Spain<br />

Spain’s problem is an excess of private debt, which<br />

can be traced back to the interest rate shock due to<br />

the EMU accession. Historically loose credit<br />

conditions led to a massive credit expansion and<br />

debt accumulation by both households and<br />

corporations, which was associated with a boom in<br />

the housing market and growing external deficits.<br />

The financial crisis has triggered a sharp adjustment<br />

in most of these imbalances (Chart 5) which has<br />

already taken a significant toll on domestic demand<br />

(-6.5% y/y in 2009), employment (unemployment just<br />

Luigi Speranza / Eoin O’Callaghan 7 May 2010<br />

<strong>Market</strong> Mover<br />

8<br />

www.Global<strong>Market</strong>s.bnpparibas.com