IJUP08 - Universidade do Porto

IJUP08 - Universidade do Porto

IJUP08 - Universidade do Porto

- TAGS

- universidade

- porto

- ijup.up.pt

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Geometry and Space Conception the importance of the processes<br />

of representation to Architecture<br />

Bruno Russo 1 and João Pedro Xavier 2<br />

1 Faculty of Architecture, University of <strong>Porto</strong>, Portugal.<br />

2 Doctor, Professor of Geometry, Faculty of Architecture, University of <strong>Porto</strong>, Portugal.<br />

What is the nature of space? What is our concept of space? Has it been unchangeable over<br />

time? And how <strong>do</strong> the architects use this concept, or concepts, in order to create<br />

architecture, the organization of space? The search for the idea of space starts at the<br />

crossroads of Geometry and Architecture. If the latter is its organization and management,<br />

the first, more than the science that studies space, is its very language, the ultimate tool for<br />

the architect, even if sometimes he’s not aware of it. Geometry and Architecture have<br />

evolved through time and their paths have often crossed, causing echoes on the individual<br />

development of each.<br />

Starting at Euclid’s Elements, the cornerstone of the western knowledge on geometry, and<br />

following the major breakthroughs of this science of space, we try to understand the<br />

influence they set on architectural production. On the other hand, by identifying turning<br />

points on Architecture’s theory and/or practice we’ll search for reverberations on the<br />

representation processes in particular, and on Geometry in general.<br />

Architecture owes Geometry what Vitruvius called dispositio – the representation<br />

processes. And since the ancient Greeks those processes have evolved: Euclid thought of<br />

an infinite and plane space (Euclidean Space), Brunelleschi, Alberti and Piero della<br />

Francesca invented the Perspectiva Artificialis, Desargues and Poncelet developed the<br />

Projective Geometry, Monge codified a <strong>do</strong>uble-projection system, Lobachevsky, Bolyai<br />

and others discovered the non-euclidean geometries, used by Einstein to re-design our<br />

model of the Universe and finally, at the turn of the millennium, the computer-based<br />

design knows mass use and becomes the only tool for many young architects.<br />

The architects used the tools Geometry provided them, and “tuned” them. We cannot sever<br />

perspective or Monge’s system from Architecture, and certainly can’t dissociate the<br />

classical orders from Pythagoras’ view of the World. Nowadays we get entangled in an<br />

overwhelming variety of forms and geometries, in a lack of “order” for the architect to<br />

follow. Architecture pursued geometric values on the search of beauty and order for many<br />

centuries, but now it seems these values have changed. Or have they not?<br />

We think that the relationship between Architecture and Geometry is a symbiosis that can’t<br />

be easily broken. We believe that the study of the history of Geometry can help us<br />

understand the history of Architecture. Today we have more knowledge, more technology,<br />

advanced engineering and higher levels of education. We need to know better the tools at<br />

our disposal in order to produce better architecture. Geometry has always been our<br />

premium tool but now, with the automation of the processes brought to light by the<br />

personal computer, we tend to distance ourselves from the geometric definition of space<br />

and form. And this can lead to a poorer comprehension of space, preventing Architecture<br />

from achieving higher goals.<br />

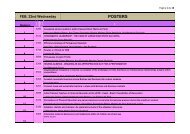

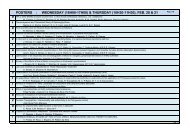

158