Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film

Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film

Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Chile<br />

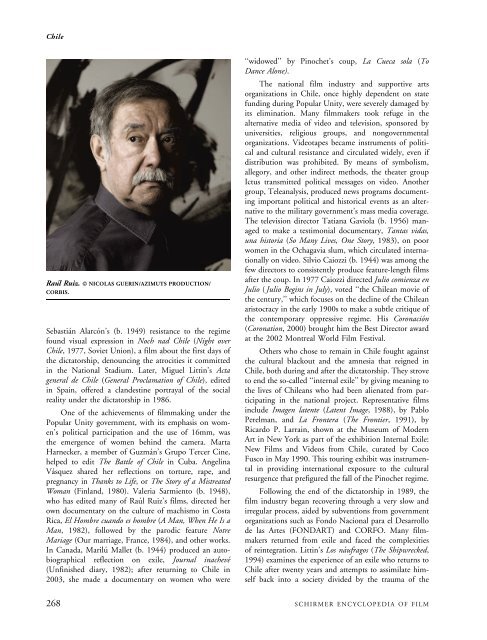

Raúl Ruiz. Ó NICOLASGUERIN/AZIMUTSPRODUCTION/<br />

CORBIS.<br />

Sebastián Alarcón’s (b. 1949) resistance to the regime<br />

found visual expression in Noch nad Chile (Night over<br />

Chile, 1977, Soviet Union), a film about the first days <strong>of</strong><br />

the dictatorship, denouncing the atrocities it committed<br />

in the National Stadium. Later, Miguel Littin’s Acta<br />

general de Chile (General Proclamation <strong>of</strong> Chile), edited<br />

in Spain, <strong>of</strong>fered a clandestine portrayal <strong>of</strong> the social<br />

reality under the dictatorship in 1986.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the achievements <strong>of</strong> filmmaking under the<br />

Popular Unity government, with its emphasis on women’s<br />

political participation and the use <strong>of</strong> 16mm, was<br />

the emergence <strong>of</strong> women behind the camera. Marta<br />

Harnecker, a member <strong>of</strong> Guzmán’s Grupo Tercer Cine,<br />

helped to edit The Battle <strong>of</strong> Chile in Cuba. Angelina<br />

Vásquez shared her reflections on torture, rape, and<br />

pregnancy in Thanks to Life, orThe Story <strong>of</strong> a Mistreated<br />

Woman (Finland, 1980). Valeria Sarmiento (b. 1948),<br />

who has edited many <strong>of</strong> Raúl Ruiz’s films, directed her<br />

own documentary on the culture <strong>of</strong> machismo in Costa<br />

Rica, El Hombre cuando es hombre (A Man, When He Is a<br />

Man, 1982), followed by the parodic feature Notre<br />

Mariage (Our marriage, France, 1984), and other works.<br />

In Canada, Marilú Mallet (b. 1944) produced an autobiographical<br />

reflection on exile, Journal inachevé<br />

(Unfinished diary, 1982); after returning to Chile in<br />

2003, she made a documentary on women who were<br />

‘‘widowed’’ by Pinochet’s coup, La Cueca sola (To<br />

Dance Alone).<br />

The national film industry and supportive arts<br />

organizations in Chile, once highly dependent on state<br />

funding during Popular Unity, were severely damaged by<br />

its elimination. Many filmmakers took refuge in the<br />

alternative media <strong>of</strong> video and television, sponsored by<br />

universities, religious groups, and nongovernmental<br />

organizations. Videotapes became instruments <strong>of</strong> political<br />

and cultural resistance and circulated widely, even if<br />

distribution was prohibited. By means <strong>of</strong> symbolism,<br />

allegory, and other indirect methods, the theater group<br />

Ictus transmitted political messages on video. Another<br />

group, Teleanalysis, produced news programs documenting<br />

important political and historical events as an alternative<br />

to the military government’s mass media coverage.<br />

The television director Tatiana Gaviola (b. 1956) managed<br />

to make a testimonial documentary, Tantas vidas,<br />

una historia (So Many Lives, One Story, 1983), on poor<br />

women in the Ochagavia slum, which circulated internationally<br />

on video. Silvio Caiozzi (b. 1944) was among the<br />

few directors to consistently produce feature-length films<br />

after the coup. In 1977 Caiozzi directed Julio comienza en<br />

Julio ( Julio Begins in July), voted ‘‘the Chilean movie <strong>of</strong><br />

the century,’’ which focuses on the decline <strong>of</strong> the Chilean<br />

aristocracy in the early 1900s to make a subtle critique <strong>of</strong><br />

the contemporary oppressive regime. His Coronación<br />

(Coronation, 2000) brought him the Best Director award<br />

at the 2002 Montreal World <strong>Film</strong> Festival.<br />

Others who chose to remain in Chile fought against<br />

the cultural blackout and the amnesia that reigned in<br />

Chile, both during and after the dictatorship. They strove<br />

to end the so-called ‘‘internal exile’’ by giving meaning to<br />

the lives <strong>of</strong> Chileans who had been alienated from participating<br />

in the national project. Representative films<br />

include Imagen latente (Latent Image, 1988), by Pablo<br />

Perelman, and La Frontera (The Frontier, 1991), by<br />

Ricardo P. Larrain, shown at the Museum <strong>of</strong> Modern<br />

Art in New York as part <strong>of</strong> the exhibition Internal Exile:<br />

New <strong>Film</strong>s and Videos from Chile, curated by Coco<br />

Fusco in May 1990. This touring exhibit was instrumental<br />

in providing international exposure to the cultural<br />

resurgence that prefigured the fall <strong>of</strong> the Pinochet regime.<br />

Following the end <strong>of</strong> the dictatorship in 1989, the<br />

film industry began recovering through a very slow and<br />

irregular process, aided by subventions from government<br />

organizations such as Fondo Nacional para el Desarrollo<br />

de las Artes (FONDART) and CORFO. Many filmmakers<br />

returned from exile and faced the complexities<br />

<strong>of</strong> reintegration. Littin’s Los náufragos (The Shipwrecked,<br />

1994) examines the experience <strong>of</strong> an exile who returns to<br />

Chile after twenty years and attempts to assimilate himself<br />

back into a society divided by the trauma <strong>of</strong> the<br />

268 SCHIRMER ENCYCLOPEDIA OF FILM