- Page 1 and 2:

Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film

- Page 3 and 4:

Project Editor Michael J. Tyrkus Ed

- Page 5 and 6:

VOLUME 1 Contents Preface IX List o

- Page 7 and 8:

PREFACE subject in English. In a fe

- Page 9 and 10:

LIST OF ARTICLES CO-PRODUCTIONS Mar

- Page 11 and 12:

LIST OF ARTICLES UNIVERSAL Thomas S

- Page 13 and 14:

Academy Awards Ò members fund the

- Page 15 and 16:

Academy Awards Ò Denzel Washington

- Page 17 and 18:

Academy Awards Ò KATHARINE HEPBURN

- Page 19 and 20:

Academy Awards Ò Katharine Hepburn

- Page 21 and 22:

The performances seen in films refl

- Page 23 and 24:

films and high-concept blockbusters

- Page 25 and 26:

However, in contrast to media celeb

- Page 27 and 28:

encounter film performances. Anothe

- Page 29 and 30:

John Cassavetes. EVERETT COLLECTION

- Page 31 and 32:

Bertolt Brecht. EVERETT COLLECTION.

- Page 33 and 34:

Portrait of Marlon Brando at the ti

- Page 35 and 36:

Pearson, Roberta E. Eloquent Gestur

- Page 37 and 38:

Action and Adventure Films Bruce Wi

- Page 39 and 40:

Action and Adventure Films ERROL FL

- Page 41 and 42:

Action and Adventure Films and high

- Page 43 and 44:

Action and Adventure Films Arnold S

- Page 45 and 46:

It seems certain that the first ‘

- Page 47 and 48:

the Garbo vehicle A Woman of Affair

- Page 49 and 50:

JOHN HUSTON b. Nevada, Missouri, 5

- Page 51 and 52:

provide formidable barriers that ha

- Page 53 and 54:

RAYMOND CHANDLER b. Chicago, Illino

- Page 55 and 56:

Witches of Salem, 1957), from The C

- Page 57 and 58:

Africa South of the Sahara Senegale

- Page 59 and 60:

Africa South of the Sahara ‘‘pu

- Page 61 and 62:

Africa South of the Sahara Emitai (

- Page 63 and 64:

Africa South of the Sahara employin

- Page 65 and 66:

Africa South of the Sahara cultures

- Page 67 and 68:

African American Cinema Spike Lee

- Page 69 and 70:

African American Cinema OSCAR MICHE

- Page 71 and 72:

African American Cinema Sidney Poit

- Page 73 and 74:

African American Cinema Sidney Poit

- Page 75 and 76:

African American Cinema characters

- Page 77 and 78:

African American Cinema Spike Lee.

- Page 79 and 80:

Agents and Agencies from numerous e

- Page 81 and 82:

Agents and Agencies LEW WASSERMAN b

- Page 83 and 84:

Agents and Agencies motion pictures

- Page 85 and 86:

‘‘Actors are cattle,’’ Alfr

- Page 87 and 88:

created by using a real tarantula a

- Page 89 and 90:

Courage of Lassie (1946), with Eliz

- Page 91 and 92:

Even in the contemporary era, when

- Page 93 and 94:

of short stop-motion films made by

- Page 95 and 96:

Pal’s legacy in Europe has been s

- Page 97 and 98:

Jan Svankmajer. JAN SVANKMAJER/ATHA

- Page 99 and 100:

CORE Digital Pictures in Toronto, C

- Page 101 and 102:

Norman McLaren. Ó CORBIS KIPA. Wha

- Page 103 and 104:

The ‘‘Arab world’’ constitu

- Page 105 and 106:

influenced film practice in other A

- Page 107 and 108:

Elia Suleiman. EVERETT COLLECTION.

- Page 109 and 110:

Manal Khader in Divine Intervention

- Page 111 and 112:

Film and television history can onl

- Page 113 and 114:

HENRI LANGLOIS b. Smryna (Izmir), T

- Page 115 and 116:

The National Film Preservation Boar

- Page 117 and 118:

Argentine filmmaking dates approxim

- Page 119 and 120:

attention, but none has yet to atta

- Page 121 and 122:

The term ‘‘art cinema’’ is

- Page 123 and 124:

Michelangelo Antonioni. Ó JOHN SPR

- Page 125 and 126:

that run counter to the body of con

- Page 127 and 128:

filmmakers Akira Kurosawa (1910-199

- Page 129 and 130:

ASIANAMERICANCINEMA Asian American

- Page 131 and 132:

The ‘‘white man’s burden’

- Page 133 and 134:

Named after John Wayne, Wang studie

- Page 135 and 136:

an Asian American context. However,

- Page 137 and 138:

Between 1910 and 1912, eighty Austr

- Page 139 and 140:

improving American sales, Longford

- Page 141 and 142:

Peter Weir shooting The Mosquito Co

- Page 143 and 144:

the strange volcanic rocks at Hangi

- Page 145 and 146:

Jane Campion at the time of Sweetie

- Page 147 and 148:

AUTEUR THEORY AND AUTHORSHIP Transl

- Page 149 and 150:

HOWARD HAWKS b. Goshen, Indiana, 30

- Page 151 and 152:

the originality of the auteur lies

- Page 153 and 154:

pasts, helping ideas about authorsh

- Page 155 and 156:

In important respects—and this wa

- Page 157 and 158:

journalism, relatively untroubled b

- Page 159 and 160:

BMovies Edgar G. Ulmer’s The Man

- Page 161 and 162:

BMovies as Jane Eyre (1934). Monogr

- Page 163 and 164:

BMovies Edgar G. Ulmer. EVERETT COL

- Page 165 and 166:

BMovies Okuda, Ted. The Monogram Ch

- Page 167 and 168:

Biography more unlikely, see at pub

- Page 169 and 170:

Biography Ken Russell’s The Music

- Page 171 and 172:

Biography Ken Russell has had a mul

- Page 173 and 174:

Biography Bingham, Dennis. ‘‘I

- Page 175 and 176:

Brazil Brazilian audience through i

- Page 177 and 178:

Brazil Carlos ‘‘Cacá’’ Die

- Page 179 and 180:

Brazil Challenge, Paulo Saraceni, 1

- Page 181 and 182:

Brazil expressed by Arnaldo Jabor (

- Page 183 and 184:

The motion picture camera is the ba

- Page 185 and 186:

THOMAS ALVA EDISON b. Milan, Ohio,

- Page 187 and 188:

Light from external subject Lens Di

- Page 189 and 190:

will look like. Because it is not a

- Page 191 and 192:

Richard Leacock (center) with Rober

- Page 193 and 194:

CAMERA MOVEMENT Camera movement is

- Page 195 and 196:

Kenji Mizoguchi. THE KOBAL COLLECTI

- Page 197 and 198:

to use zooms more frequently beginn

- Page 199 and 200:

cranes up to a great height, reveal

- Page 201 and 202:

Max Ophüls. MAX OPHÜLS/THE KOBAL

- Page 203 and 204:

FURTHER READING Bazin, André. What

- Page 205 and 206:

Canada north, they’ll soon be dri

- Page 207 and 208:

Canada dialogue and script, shootin

- Page 209 and 210:

Canada Typical Canadian losers Doug

- Page 211 and 212:

Canada Born in Egypt to Armenian pa

- Page 213 and 214:

Canada Morris, Peter. Embattled Sha

- Page 215 and 216:

Canon and Canonicity served as a re

- Page 217 and 218:

Canon and Canonicity same time, gro

- Page 219 and 220:

Cartoons Winsor McCay’s Gertie th

- Page 221 and 222:

Cartoons CHUCK JONES b. Spokane, Wa

- Page 223 and 224:

Cartoons Chuck Jones parodied Wagne

- Page 225 and 226:

Casting is one of the least underst

- Page 227 and 228:

Charles Coburn when looking for a w

- Page 229 and 230:

Lynn Stalmaster. KEVIN WINTER/GETTY

- Page 231 and 232:

fame: John Wayne as Genghis Khan in

- Page 233 and 234:

Censorship WILL H. HAYS b. William

- Page 235 and 236:

Censorship The suggestive image of

- Page 237 and 238:

Censorship Peter Watkins’s The Wa

- Page 239 and 240:

Censorship ‘‘indecency,’’ w

- Page 241 and 242:

Character Actors public also embrac

- Page 243 and 244:

Character Actors Prominent American

- Page 245 and 246:

Character Actors SEE ALSO Acting; C

- Page 247 and 248:

Child Actors Jackie Cooper with Wal

- Page 249 and 250:

Child Actors Shirley Temple was an

- Page 251 and 252:

Child Actors Most young actors in t

- Page 253 and 254:

Children’s films may be divided i

- Page 255 and 256:

most in the realm of animated featu

- Page 257 and 258:

disability issues. Oliver! (1968) b

- Page 259 and 260:

Chilean cinema emerged at the turn

- Page 261 and 262:

Raúl Ruiz studied law and theology

- Page 263 and 264:

dictatorship; Gringuito (Sergio Cas

- Page 265 and 266:

China 1934), both depicting the pli

- Page 267 and 268:

China Gong Li in Zhang Yimou’s Ra

- Page 269 and 270:

China Zhang Yimou. PHOTO BY S. SARA

- Page 271 and 272:

The job of choreographer or dance d

- Page 273 and 274:

Roy Scheider as choreographer Joe G

- Page 275 and 276:

Bob Fosse on the set of All That Ja

- Page 277 and 278:

Cinematography Gregg Toland’s dee

- Page 279 and 280:

Cinematography GREGG TOLAND b. Char

- Page 281 and 282:

Cinematography will appear in crisp

- Page 283 and 284:

Cinematography Néstor Almendros wi

- Page 285 and 286:

Cinematography James Wong Howe’s

- Page 287 and 288:

Cinematography Néstor Almendros’

- Page 289 and 290:

The first filmgoers who referred to

- Page 291 and 292:

wars of high and low categories of

- Page 293 and 294:

‘‘Class’’ is a term used to

- Page 295 and 296:

to be the most important art form

- Page 297 and 298:

Mike Leigh. PHOTOBYCJCONTINO/EVERET

- Page 299 and 300:

acism, sexism, and militarism). Goi

- Page 301 and 302:

The science fiction film Strange In

- Page 303 and 304:

answer questions that would have in

- Page 305 and 306:

Edward Dmytryk on location directin

- Page 307 and 308:

Dalton Trumbo. EVERETT COLLECTION.

- Page 309 and 310:

number (57) of Communists he claims

- Page 311 and 312:

A Hollywood myth has it that the co

- Page 313 and 314:

and his gifted cameraman Gunnar Fis

- Page 315 and 316:

COLONIALISM AND POSTCOLONIALISM Amo

- Page 317 and 318:

Although the visual artist Tracey M

- Page 319 and 320:

(Robert Flaherty, 1922), but also c

- Page 321 and 322:

notice, such as in Once Were Warrio

- Page 323 and 324:

Color The Wizard of Oz (Victor Flem

- Page 325 and 326:

Color HERBERT THOMAS KALMUS b. Bost

- Page 327 and 328:

Color Monica Vitti in Il Deserto ro

- Page 329 and 330:

Color The Band Wagon (Vincente Minn

- Page 331 and 332:

The rise of Columbia Pictures to Ho

- Page 333 and 334: HARRY COHN b. New York, New York, 2

- Page 335 and 336: not only scripted but also informal

- Page 337 and 338: Rita Hayworth in Gilda (Charles Vid

- Page 339 and 340: From Here to Eternity (1953), On th

- Page 341 and 342: In a valuable insight on the nature

- Page 343 and 344: Ferrell (b. 1967) fails as a toymak

- Page 345 and 346: Charlie Chaplin in 1936, the year o

- Page 347 and 348: Parody is often enhanced by various

- Page 349 and 350: ‘‘boy-meets-girl’’ formula

- Page 351 and 352: FURTHER READING Bergson, Henri. Lau

- Page 353 and 354: Comics and Comic Books than three h

- Page 355 and 356: Comics and Comic Books Among the mo

- Page 357 and 358: Co-productions other languages as w

- Page 359 and 360: Co-productions sion programs throug

- Page 361 and 362: Costume design is as crucial to the

- Page 363 and 364: out contradictions such as Walter P

- Page 365 and 366: ADRIAN b. Adrian Adolph Greenburg,

- Page 367 and 368: Piero Gherardi’s extreme costumes

- Page 369 and 370: The word ‘‘credits’’ refers

- Page 371 and 372: Saul Bass. EVERETT COLLECTION. REPR

- Page 373 and 374: Saul Bass’s credits for Otto Prem

- Page 375 and 376: multiple exposures, and the musical

- Page 377 and 378: Crew The size and diversity of mode

- Page 379 and 380: Crew VISUAL DESIGN The production d

- Page 381 and 382: Crew musical score is designed by a

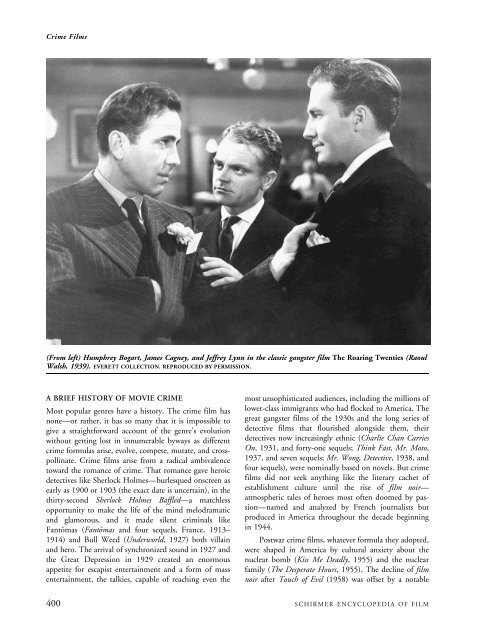

- Page 383: Crime films rule the world from Eas

- Page 387 and 388: HUMPHREY BOGART b. New York, New Yo

- Page 389 and 390: victim in Midnight in the Garden of

- Page 391 and 392: Born in Queens, Martin Scorsese gre

- Page 393: Krutnik, Frank. In a Lonely Street: