Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film

Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film

Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Adaptation<br />

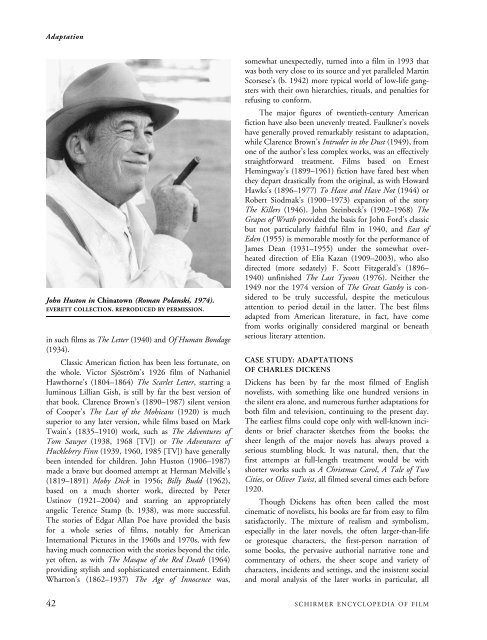

John Huston in Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 1974).<br />

EVERETT COLLECTION. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.<br />

in such films as The Letter (1940) and Of Human Bondage<br />

(1934).<br />

Classic American fiction has been less fortunate, on<br />

the whole. Victor Sjöström’s 1926 film <strong>of</strong> Nathaniel<br />

Hawthorne’s (1804–1864) The Scarlet Letter, starring a<br />

luminous Lillian Gish, is still by far the best version <strong>of</strong><br />

that book. Clarence Brown’s (1890–1987) silent version<br />

<strong>of</strong> Cooper’s The Last <strong>of</strong> the Mohicans (1920) is much<br />

superior to any later version, while films based on Mark<br />

Twain’s (1835–1910) work, such as The Adventures <strong>of</strong><br />

Tom Sawyer (1938, 1968 [TV]) or The Adventures <strong>of</strong><br />

Hucklebrry Finn (1939, 1960, 1985 [TV]) have generally<br />

been intended for children. John Huston (1906–1987)<br />

made a brave but doomed attempt at Herman Melville’s<br />

(1819–1891) Moby Dick in 1956; Billy Budd (1962),<br />

based on a much shorter work, directed by Peter<br />

Ustinov (1921–2004) and starring an appropriately<br />

angelic Terence Stamp (b. 1938), was more successful.<br />

The stories <strong>of</strong> Edgar Allan Poe have provided the basis<br />

for a whole series <strong>of</strong> films, notably for American<br />

International Pictures in the 1960s and 1970s, with few<br />

having much connection with the stories beyond the title,<br />

yet <strong>of</strong>ten, as with The Masque <strong>of</strong> the Red Death (1964)<br />

providing stylish and sophisticated entertainment. Edith<br />

Wharton’s (1862–1937) The Age <strong>of</strong> Innocence was,<br />

somewhat unexpectedly, turned into a film in 1993 that<br />

was both very close to its source and yet paralleled Martin<br />

Scorsese’s (b. 1942) more typical world <strong>of</strong> low-life gangsters<br />

with their own hierarchies, rituals, and penalties for<br />

refusing to conform.<br />

The major figures <strong>of</strong> twentieth-century American<br />

fiction have also been unevenly treated. Faulkner’s novels<br />

have generally proved remarkably resistant to adaptation,<br />

while Clarence Brown’s Intruder in the Dust (1949), from<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the author’s less complex works, was an effectively<br />

straightforward treatment. <strong>Film</strong>s based on Ernest<br />

Hemingway’s (1899–1961) fiction have fared best when<br />

they depart drastically from the original, as with Howard<br />

Hawks’s (1896–1977) To Have and Have Not (1944) or<br />

Robert Siodmak’s (1900–1973) expansion <strong>of</strong> the story<br />

The Killers (1946). John Steinbeck’s (1902–1968) The<br />

Grapes <strong>of</strong> Wrath provided the basis for John Ford’s classic<br />

but not particularly faithful film in 1940, and East <strong>of</strong><br />

Eden (1955) is memorable mostly for the performance <strong>of</strong><br />

James Dean (1931–1955) under the somewhat overheated<br />

direction <strong>of</strong> Elia Kazan (1909–2003), who also<br />

directed (more sedately) F. Scott Fitzgerald’s (1896–<br />

1940) unfinished The Last Tycoon (1976). Neither the<br />

1949 nor the 1974 version <strong>of</strong> The Great Gatsby is considered<br />

to be truly successful, despite the meticulous<br />

attention to period detail in the latter. The best films<br />

adapted from American literature, in fact, have come<br />

from works originally considered marginal or beneath<br />

serious literary attention.<br />

CASE STUDY: ADAPTATIONS<br />

OF CHARLES DICKENS<br />

Dickens has been by far the most filmed <strong>of</strong> English<br />

novelists, with something like one hundred versions in<br />

the silent era alone, and numerous further adaptations for<br />

both film and television, continuing to the present day.<br />

The earliest films could cope only with well-known incidents<br />

or brief character sketches from the books; the<br />

sheer length <strong>of</strong> the major novels has always proved a<br />

serious stumbling block. It was natural, then, that the<br />

first attempts at full-length treatment would be with<br />

shorter works such as A Christmas Carol, A Tale <strong>of</strong> Two<br />

Cities,orOliver Twist, all filmed several times each before<br />

1920.<br />

Though Dickens has <strong>of</strong>ten been called the most<br />

cinematic <strong>of</strong> novelists, his books are far from easy to film<br />

satisfactorily. The mixture <strong>of</strong> realism and symbolism,<br />

especially in the later novels, the <strong>of</strong>ten larger-than-life<br />

or grotesque characters, the first-person narration <strong>of</strong><br />

some books, the pervasive authorial narrative tone and<br />

commentary <strong>of</strong> others, the sheer scope and variety <strong>of</strong><br />

characters, incidents and settings, and the insistent social<br />

and moral analysis <strong>of</strong> the later works in particular, all<br />

42 SCHIRMER ENCYCLOPEDIA OF FILM