Yellowstone's Northern Range - Greater Yellowstone Science ...

Yellowstone's Northern Range - Greater Yellowstone Science ...

Yellowstone's Northern Range - Greater Yellowstone Science ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

HISTORY OF RESEARCH AND MANAGEMENT<br />

was to regulate and manage <strong><strong>Yellowstone</strong>'s</strong> northern<br />

range so that its production of elk was more or less<br />

unvarying and predictable, and so that winter<br />

mortality did not occur or was kept to some ideal<br />

minimum.<br />

In the 1920s and 1930s, coucern over the<br />

condition of the range grew, as the elk population<br />

was repeatedly described as too large. Other<br />

aspects of the northern range came to the attention<br />

of observers. Skinner (1929) reported a decline in<br />

the park's white-tailed deer population, from 100 at<br />

the beginning of the 1900s to essentially none by<br />

the late 1920s. In 1931, Talbot reported an increase<br />

in exotic plant species and erosion, attributing these<br />

to overgrazing (Tyers 1981).<br />

The most important of these investigations<br />

was conducted by U.S. Forest Service biologist W.<br />

M. Rush (1927, 1932). Based on horseback trips<br />

through part of the northern <strong>Yellowstone</strong> elk winter<br />

range in 1914 and 1927, Rush concluded that<br />

drought and grazing had lowered range carrying<br />

capacity, that erosion was widespread, that exotics<br />

continued to invade, and that all browse species<br />

would be lost if something were not done. Houston<br />

(1982) pointed out that "Rush recognized the<br />

cursory and subjective nahlre of his range assessments,<br />

a fact which seems to have been overlooked<br />

7<br />

in subsequent references to his findings." Tyers<br />

(1981) and Houston (1982) summarized the work<br />

done by subsequent National Park Service biologists,<br />

especially R. Grimm and W. Kittams between<br />

1933 and 1958, both of whom generally supported<br />

Rush's conclusions. By the early 1960s, the<br />

"<strong>Yellowstone</strong> elk problem" had become one of the<br />

longest-standing dilemmas in American wildlife<br />

management history. In June 1963, Cooper et al.<br />

made a 12-day survey of the northern range and<br />

estimated a winter elk carrying capacity of about<br />

5,000, in keeping with several earlier estimates and<br />

using standards usually applied to domestic<br />

livestock grazing (Cooper et al. 1963).<br />

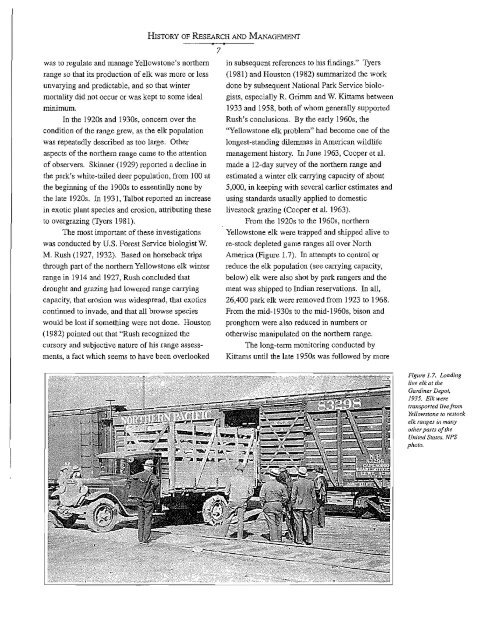

From the 1920s to the 1960s, northern<br />

<strong>Yellowstone</strong> elk were trapped and shipped alive to<br />

re-stock depleted game ranges all over North<br />

America (Figure 1.7). In attempts to control or<br />

reduce the elk population (see carrying capacity,<br />

below) elk were also shot by park rangers and the<br />

meat was shipped to Indian reservations. In all,<br />

26,400 park elk were removed from 1923 to 1968.<br />

From the mid-1930s to the mid-1960s, bison and<br />

pronghorn were also reduced in numbers or<br />

otherwise manipulated on the northern range.<br />

The long-term monitoring conducted by<br />

Kittams until the late 1950s was followed by more<br />

Figure 1.7. Loading<br />

live elk at the<br />

Gardiner Depot,<br />

1935. Elk were<br />

transported live from<br />

<strong>Yellowstone</strong> to restock<br />

elk ranges in many<br />

other parts of the<br />

United States. NPS<br />

photo.