Education guide 'Eindhoven designs' - Technische Universiteit ...

Education guide 'Eindhoven designs' - Technische Universiteit ...

Education guide 'Eindhoven designs' - Technische Universiteit ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

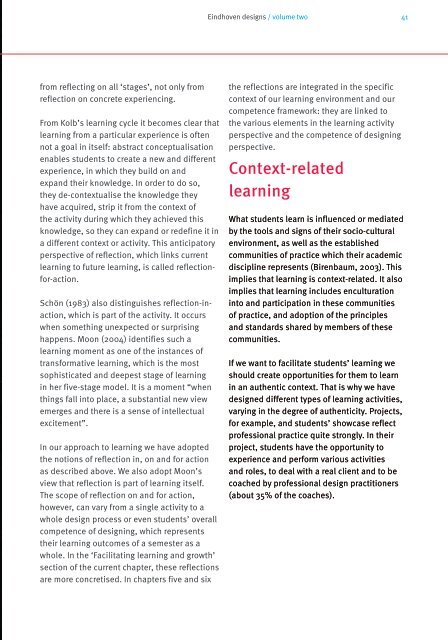

Eindhoven designs / volume two 41<br />

from reflecting on all ‘stages’, not only from<br />

reflection on concrete experiencing.<br />

From Kolb’s learning cycle it becomes clear that<br />

learning from a particular experience is often<br />

not a goal in itself: abstract conceptualisation<br />

enables students to create a new and different<br />

experience, in which they build on and<br />

expand their knowledge. In order to do so,<br />

they de-contextualise the knowledge they<br />

have acquired, strip it from the context of<br />

the activity during which they achieved this<br />

knowledge, so they can expand or redefine it in<br />

a different context or activity. This anticipatory<br />

perspective of reflection, which links current<br />

learning to future learning, is called reflectionfor-action.<br />

Schön (1983) also distinguishes reflection-inaction,<br />

which is part of the activity. It occurs<br />

when something unexpected or surprising<br />

happens. Moon (2004) identifies such a<br />

learning moment as one of the instances of<br />

transformative learning, which is the most<br />

sophisticated and deepest stage of learning<br />

in her five-stage model. It is a moment “when<br />

things fall into place, a substantial new view<br />

emerges and there is a sense of intellectual<br />

excitement”.<br />

In our approach to learning we have adopted<br />

the notions of reflection in, on and for action<br />

as described above. We also adopt Moon’s<br />

view that reflection is part of learning itself.<br />

The scope of reflection on and for action,<br />

however, can vary from a single activity to a<br />

whole design process or even students’ overall<br />

competence of designing, which represents<br />

their learning outcomes of a semester as a<br />

whole. In the ‘Facilitating learning and growth’<br />

section of the current chapter, these reflections<br />

are more concretised. In chapters five and six<br />

the reflections are integrated in the specific<br />

context of our learning environment and our<br />

competence framework: they are linked to<br />

the various elements in the learning activity<br />

perspective and the competence of designing<br />

perspective.<br />

Context-related<br />

learning<br />

What students learn is influenced or mediated<br />

by the tools and signs of their socio-cultural<br />

environment, as well as the established<br />

communities of practice which their academic<br />

discipline represents (Birenbaum, 2003). This<br />

implies that learning is context-related. It also<br />

implies that learning includes enculturation<br />

into and participation in these communities<br />

of practice, and adoption of the principles<br />

and standards shared by members of these<br />

communities.<br />

If we want to facilitate students’ learning we<br />

should create opportunities for them to learn<br />

in an authentic context. That is why we have<br />

designed different types of learning activities,<br />

varying in the degree of authenticity. Projects,<br />

for example, and students’ showcase reflect<br />

professional practice quite strongly. In their<br />

project, students have the opportunity to<br />

experience and perform various activities<br />

and roles, to deal with a real client and to be<br />

coached by professional design practitioners<br />

(about 35% of the coaches).