Thesis document - Jana Milosovicova - Urban Design English

Thesis document - Jana Milosovicova - Urban Design English

Thesis document - Jana Milosovicova - Urban Design English

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

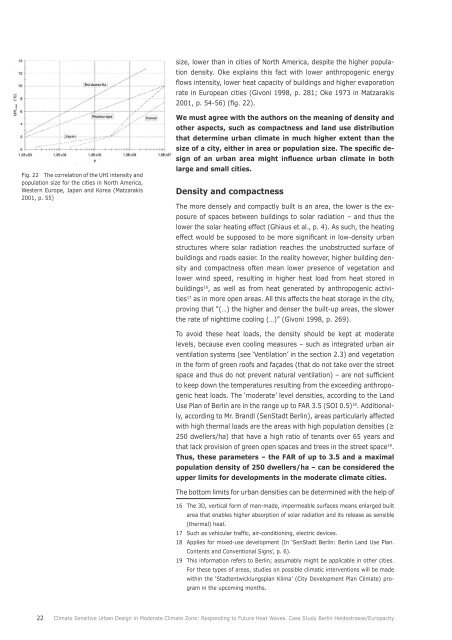

size, lower than in cities of North America, despite the higher populationdensity. Oke explains this fact with lower anthropogenic energyflows intensity, lower heat capacity of buildings and higher evaporationrate in European cities (Givoni 1998, p. 281; Oke 1973 in Matzarakis2001, p. 54-56) (fig. 22).Fig. 22 The correlation of the UHI intensity andpopulation size for the cities in North America,Western Europe, Japan and Korea (Matzarakis2001, p. 55)We must agree with the authors on the meaning of density andother aspects, such as compactness and land use distributionthat determine urban climate in much higher extent than thesize of a city, either in area or population size. The specific designof an urban area might influence urban climate in bothlarge and small cities.Density and compactnessThe more densely and compactly built is an area, the lower is the exposureof spaces between buildings to solar radiation – and thus thelower the solar heating effect (Ghiaus et al., p. 4). As such, the heatingeffect would be supposed to be more significant in low-density urbanstructures where solar radiation reaches the unobstructed surface ofbuildings and roads easier. In the reality however, higher building densityand compactness often mean lower presence of vegetation andlower wind speed, resulting in higher heat load from heat stored inbuildings 16 , as well as from heat generated by anthropogenic activities17 as in more open areas. All this affects the heat storage in the city,proving that “(…) the higher and denser the built-up areas, the slowerthe rate of nighttime cooling (…)” (Givoni 1998, p. 269).To avoid these heat loads, the density should be kept at moderatelevels, because even cooling measures – such as integrated urban airventilation systems (see ‘Ventilation’ in the section 2.3) and vegetationin the form of green roofs and façades (that do not take over the streetspace and thus do not prevent natural ventilation) – are not sufficientto keep down the temperatures resulting from the exceeding anthropogenicheat loads. The ‘moderate’ level densities, according to the LandUse Plan of Berlin are in the range up to FAR 3.5 (SOI 0.5) 18 . Additionally,according to Mr. Brandl (SenStadt Berlin), areas particularly affectedwith high thermal loads are the areas with high population densities (≥250 dwellers/ha) that have a high ratio of tenants over 65 years andthat lack provision of green open spaces and trees in the street space 19 .Thus, these parameters – the FAR of up to 3.5 and a maximalpopulation density of 250 dwellers/ha – can be considered theupper limits for developments in the moderate climate cities.The bottom limits for urban densities can be determined with the help of16 The 3D, vertical form of man-made, impermeable surfaces means enlarged builtarea that enables higher absorption of solar radiation and its release as sensible(thermal) heat.17 Such as vehicular traffic, air-conditioning, electric devices.18 Applies for mixed-use development (In ‘SenStadt Berlin: Berlin Land Use Plan.Contents and Conventional Signs’, p. 6).19 This information refers to Berlin; assumably might be applicable in other cities.For these types of areas, studies on possible climatic interventions will be madewithin the ‘Stadtentwicklungsplan Klima’ (City Development Plan Climate) programin the upcoming months.22Climate Sensitive <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> in Moderate Climate Zone: Responding to Future Heat Waves. Case Study Berlin Heidestrasse/Europacity