FRANCE The

FRANCE The

FRANCE The

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Trends<br />

legalising illegal immigrants or by raising statutory retirement age<br />

limits (restricting the amount of pensions is not considered as a<br />

viable policy option, as pensions are rather low in Greece). Yet,<br />

apart from entailing a higher economic cost to society, demographic<br />

ageing has a number of serious implications, both economic and<br />

social 3 . Changing family structures, new living arrangements and<br />

altered relations between generations are but a few of the social<br />

consequences stemming from the rapid change. <strong>The</strong> implications of<br />

demographic change might be better understood by looking at<br />

specific age cohorts, which are of particular importance for policymaking.<br />

In this respect, the decline in the age cohort 15-24 raises the<br />

issues of education, human resource development and labour<br />

market policies for the young. Similarly, growth in the age cohort<br />

50-64 raises the issue of active ageing, while the trend concerning<br />

the age group 65 and over increases the need for social security<br />

reforms. Finally, increased numbers of very old people (80 and over)<br />

raise the issue of health and care policy planning and have<br />

implications for housing services, transport and other public<br />

infrastructures. In short, there is currently a certain lack of<br />

awareness of the wider implications of ageing among the public in<br />

general and among the politicians and the academics in particular 4 .<br />

<strong>The</strong> implications of ageing which are considered in this article relate<br />

to employment and the labour market as well as to policies aimed at<br />

stimulating active ageing.<br />

2. Trends and developments in the labour<br />

market<br />

Labour force participation rates (also known as activity rates) for<br />

older people vary according to gender, type of area and type of<br />

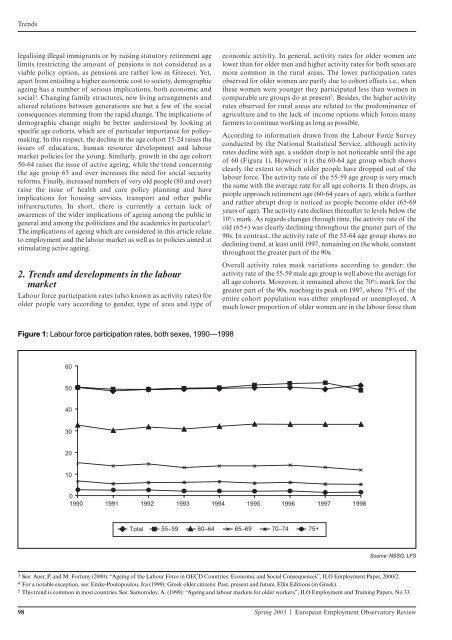

Figure 1: Labour force participation rates, both sexes, 1990—1998<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

+<br />

+<br />

+<br />

+<br />

+<br />

+<br />

+<br />

economic activity. In general, activity rates for older women are<br />

lower than for older men and higher activity rates for both sexes are<br />

more common in the rural areas. <strong>The</strong> lower participation rates<br />

observed for older women are partly due to cohort effects i.e., when<br />

these women were younger they participated less than women in<br />

comparable are groups do at present5 . Besides, the higher activity<br />

rates observed for rural areas are related to the predominance of<br />

agriculture and to the lack of income options which forces many<br />

farmers to continue working as long as possible.<br />

According to information drawn from the Labour Force Survey<br />

conducted by the National Statistical Service, although activity<br />

rates decline with age, a sudden drop is not noticeable until the age<br />

of 60 (Figure 1). However it is the 60-64 age group which shows<br />

clearly the extent to which older people have dropped out of the<br />

labour force. <strong>The</strong> activity rate of the 55-59 age group is very much<br />

the same with the average rate for all age cohorts. It then drops, as<br />

people approach retirement age (60-64 years of age), while a further<br />

and rather abrupt drop is noticed as people become older (65-69<br />

years of age). <strong>The</strong> activity rate declines thereafter to levels below the<br />

10% mark. As regards changes through time, the activity rate of the<br />

old (65+) was clearly declining throughout the greater part of the<br />

90s. In contrast, the activity rate of the 55-64 age group shows no<br />

declining trend, at least until 1997, remaining on the whole, constant<br />

throughout the greater part of the 90s.<br />

Overall activity rates mask variations according to gender: the<br />

activity rate of the 55-59 male age group is well above the average for<br />

all age cohorts. Moreover, it remained above the 70% mark for the<br />

greater part of the 90s, reaching its peak on 1997, where 75% of the<br />

entire cohort population was either employed or unemployed. A<br />

much lower proportion of older women are in the labour force than<br />

++ ++ ++ ++ ++ ++ ++ ++<br />

0<br />

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998<br />

3 See: Auer, P. and M. Fortuny (2000): “Ageing of the Labour Force in OECD Countries: Economic and Social Consequences”, ILO Employment Paper, 2000/2.<br />

4 For a notable exception, see: Emke-Poulopoulou, Ira (1999): Greek older citizens: Past, present and future, Ellin Editions (in Greek).<br />

5 This trend is common in most countries. See: Samorodov, A. (1999): “Ageing and labour markets for older workers”, ILO Employment and Training Papers, No 33.<br />

98 Spring 2003 | European Employment Observatory Review<br />

+<br />

Total 55–59 60–64 65–69 ++ 70–74 75+<br />

+<br />

+<br />

+<br />

+<br />

Source: NSSG, LFS