- Page 1:

E ARLY M EDIEVAL A RCHAEOLOGY P ROJ

- Page 5 and 6:

Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Page 7 and 8:

Table of Contents St Michael le Pol

- Page 9 and 10:

Table of Contents Knowth Site M, Co

- Page 11 and 12:

List of Figures LIST OF FIGURES Fig

- Page 13 and 14:

List of Figures Fig. 92: Excavated

- Page 15 and 16:

List of Figures Fig. 183: Plan of h

- Page 17 and 18:

List of Figures Fig. 270: Significa

- Page 19 and 20:

Introduction 1.1 Description of thi

- Page 21 and 22:

Introduction Fig. 1: Key to symbols

- Page 23 and 24:

Introduction (commonly referred to

- Page 25 and 26:

Introduction References: Campbell,

- Page 27 and 28:

County Antrim Fig. 2: Significant e

- Page 29 and 30:

Antrim Fig. 4: Plan of Antiville, C

- Page 31 and 32:

Antrim Ballyaghagan, Co. Antrim Ear

- Page 33 and 34:

Antrim Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reime

- Page 35 and 36:

Antrim Fig. 8: Plan of Phase 2 hous

- Page 37 and 38:

Antrim Fig. 9: Plan of Ballymacash,

- Page 39 and 40:

Antrim Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reime

- Page 41 and 42:

Antrim Fig. 12: Plan of interior of

- Page 43 and 44:

Antrim Fig. 13: Plan of enclosures

- Page 45 and 46:

Antrim Radiocarbon Dates (PJ Reimer

- Page 47 and 48:

Antrim Fig. 15: Plan of Ballyvollen

- Page 49 and 50:

Antrim Ballywee, Co. Antrim Early M

- Page 51 and 52:

Antrim Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reime

- Page 53 and 54:

Antrim Fig. 17: Site plan of excava

- Page 55 and 56:

Antrim ‘Craig Hill’ (Craig td.)

- Page 57 and 58:

Antrim Fig. 20: Plan of Craigywarre

- Page 59 and 60:

Antrim The mound was subsequently r

- Page 61 and 62:

Antrim Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reime

- Page 63 and 64:

Antrim ‘Doonmore’ (Cross td.),

- Page 65 and 66:

Antrim Fig. 24: Plan of House III a

- Page 67 and 68:

Antrim Fig. 25: Phase I occupation

- Page 69 and 70:

Antrim Dunsilly, Co. Antrim Early M

- Page 71 and 72:

Antrim Killealy, Co. Antrim Early M

- Page 73 and 74:

Antrim ‘Langford Lodge’ (Gartre

- Page 75 and 76:

Antrim Lissue, Co. Antrim Early Med

- Page 77 and 78:

Antrim ‘Meadowbank’ (Jordanstow

- Page 79 and 80:

Antrim Rathbeg, Co. Antrim Early Me

- Page 81 and 82:

Antrim Seacash, Co. Antrim Early Me

- Page 83 and 84:

Antrim Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reime

- Page 85 and 86:

Antrim Fig. 37: Plan of interior of

- Page 87 and 88:

Armagh Armagh (Armagh City td.), Co

- Page 89 and 90:

Armagh Fig. 40: Excavations at Cast

- Page 91 and 92:

Armagh Radiocarbon Dates: Abbey Str

- Page 93 and 94:

Armagh Dressogagh, Co. Armagh Early

- Page 95 and 96:

Armagh Terryhoogan, Co. Armagh Earl

- Page 97 and 98:

Clare ‘Beal Boru’ (Ballyvally t

- Page 99 and 100:

Clare Fig. 47: Plan of excavated ar

- Page 101 and 102:

Clare The Harvard excavators identi

- Page 103 and 104:

Clare Cahircalla More, Co. Clare Ea

- Page 105 and 106:

Clare Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer

- Page 107 and 108:

Clare Clonmoney West, Co. Clare Ear

- Page 109 and 110:

Clare were associated with glass fr

- Page 111 and 112:

Clare wooden bucket, as well as Bro

- Page 113 and 114:

Clare Gragan West, Co. Clare Early

- Page 115 and 116:

Clare Inishcealtra, Co. Clare Eccle

- Page 117 and 118:

Clare Medieval Activity Significant

- Page 119 and 120:

Clare Fig. 53: Excavated areas of I

- Page 121 and 122:

Clare Fig. 54: Plan showing enclosu

- Page 123 and 124:

Clare Fig. 55: Plan of Thady’s Fo

- Page 125 and 126:

Cork Ballyarra, Co. Cork Unenclosed

- Page 127 and 128:

Cork shape was not able to be infer

- Page 129 and 130:

Cork ‘St. Gobnet’s House’ (Gl

- Page 131 and 132:

Cork Banduff, Co. Cork Early Mediev

- Page 133 and 134:

Cork Barrees Valley, Co. Cork Early

- Page 135 and 136:

Cork Brigown, Co. Cork Early Mediev

- Page 137 and 138:

Cork Carrigaline Middle, Co. Cork E

- Page 139 and 140:

Cork Fig. 62: Plan of primary phase

- Page 141 and 142:

Cork Fig. 63: Plan of excavations a

- Page 143:

Cork The following is based on gene

- Page 146 and 147:

Cork Fig. 66: Excavated areas on th

- Page 148 and 149:

Cork apart at one of the lowest lev

- Page 150 and 151:

Cork The Scandinavian main street o

- Page 152 and 153:

Cork Fig. 68: 11-13 Washington Stre

- Page 154 and 155:

Cork Fig. 69: Hanover Street/South

- Page 156 and 157:

Cork Twelfth century bone-working i

- Page 158 and 159:

Cork Hurley, M. F. 1995. Excavation

- Page 160 and 161:

Cork Curraheen, Co. Cork Early Medi

- Page 162 and 163:

Cork Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer,

- Page 164 and 165:

Cork barrel-padlock and an anvil; a

- Page 166 and 167:

Cork Killanully, Co. Cork Early Med

- Page 168 and 169:

Cork Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer,

- Page 170 and 171:

Cork flint objects, a rotary quern

- Page 172 and 173:

Cork number of post pits and stakeh

- Page 174 and 175:

Cork bronze button, bronze brooch,

- Page 176 and 177:

Cork ‘Lisnagun’ (Darrary td.),

- Page 178 and 179:

Cork Fig. 76: Plan of interior of L

- Page 180 and 181:

Cork bracelet, a segmented bead of

- Page 182 and 183:

Cork Fig. 78: Excavated areas in Mi

- Page 184 and 185:

Cork A total of thirteen struck fli

- Page 186 and 187:

Cork A small number of un-stratifie

- Page 188 and 189:

Cork sequence of fire debris. The p

- Page 190 and 191:

Donegal Dooey, Co. Donegal Early Me

- Page 192 and 193: Donegal Fig. 82: Plan of Rinnaraw C

- Page 194 and 195: Donegal Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reim

- Page 196 and 197: Down Ballyfounder, Co. Down Early M

- Page 198 and 199: Down Ballywillwill, Co. Down Early

- Page 200 and 201: Down ‘Clea Lakes’ (Tullyveery t

- Page 202 and 203: Down Crossnacreevy, Co. Down Early

- Page 204 and 205: Down Drumadonnell, Co. Down Early M

- Page 206 and 207: Down Duneight, Co. Down Early Medie

- Page 208 and 209: Down ‘Dunnyneil Island’ (Dunnyn

- Page 210 and 211: Down Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer,

- Page 212 and 213: Down Fig. 98: Section of Gransha sh

- Page 214 and 215: Down spreads of gravel and some fir

- Page 216 and 217: Down Fig. 100: Section of Rathmulla

- Page 218 and 219: Down Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer,

- Page 220 and 221: Down Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer,

- Page 222 and 223: Down Fig. 103: Excavation at White

- Page 224 and 225: Dublin County Dublin Fig. 105: Sign

- Page 226 and 227: Dublin Ballyman, Co. Dublin Early M

- Page 228 and 229: Dublin Cherrywood (Site 18), Co. Du

- Page 230 and 231: Dublin Fig. 107: Plan of Scandinavi

- Page 232 and 233: Dublin interface of this layer and

- Page 234 and 235: Dublin Scandinavian/Hiberno-Scandin

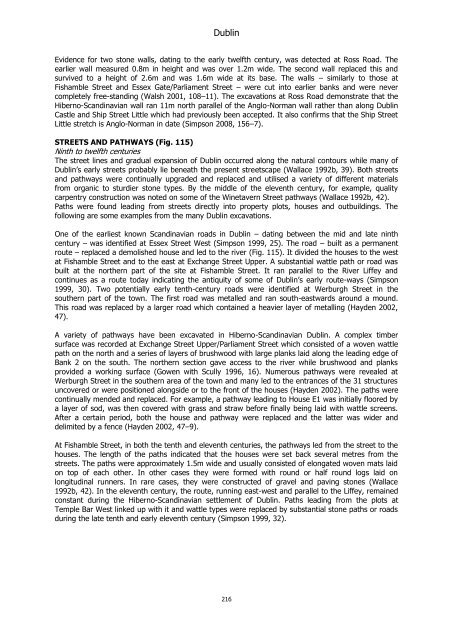

- Page 236 and 237: Dublin The following is based on ge

- Page 238 and 239: Dublin 1999, 27). Similarly dated s

- Page 240 and 241: Dublin Eleventh Century (Fig. 113)

- Page 244 and 245: Dublin Fig. 116. Reconstruction of

- Page 246 and 247: Dublin Fig. 118: Plan of Type-2 Hou

- Page 248 and 249: Dublin Excavations occurred directl

- Page 250 and 251: Dublin An amber and jet workshop wa

- Page 252 and 253: Dublin Glebe (Site 43), Co. Dublin

- Page 254 and 255: Dublin ‘Mount Offaly’, Cabintee

- Page 256 and 257: Dublin Fig. 122: Phases at Mount Of

- Page 258 and 259: Dublin a continuation of Ditch C an

- Page 260 and 261: Dublin Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reime

- Page 262 and 263: Dublin were suggestive of a number

- Page 264 and 265: Dublin Dubhlinn - a large natural p

- Page 266 and 267: Dublin Scandinavian warrior burial

- Page 268 and 269: Dublin Fig. 128: Plan of excavation

- Page 270 and 271: Dublin Gowen, M. 2001. Excavations

- Page 272 and 273: Fermanagh ‘Boho’ (Carn td.), Co

- Page 274 and 275: Fermanagh Coolcran, Co. Fermanagh E

- Page 276 and 277: Fermanagh ‘Lisdoo’ (Castle Balf

- Page 278 and 279: Fermanagh Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Re

- Page 280 and 281: Galway Ballybrit, Co. Galway Early

- Page 282 and 283: Galway Carrowkeel, Co. Galway Early

- Page 284 and 285: Galway Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reime

- Page 286 and 287: Galway Doonloughan, Co. Galway Earl

- Page 288 and 289: Galway ‘Feerwore Rath’ (Turoe t

- Page 290 and 291: Galway High Island, Co. Galway Earl

- Page 292 and 293:

Galway Loughbown (1), Co. Galway Ea

- Page 294 and 295:

Galway Loughbown (2), Co. Galway Ea

- Page 296 and 297:

Galway Mackney, Co. Galway Early Me

- Page 298 and 299:

Galway Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reime

- Page 300 and 301:

Galway Fig. 146: Excavated area at

- Page 302 and 303:

Kerry County Kerry Fig. 147: Signif

- Page 304 and 305:

Kerry Fig. 148: Plan of site showin

- Page 306 and 307:

Kerry unique mix of architectural c

- Page 308 and 309:

Kerry Bray Head, Valentia Island Ea

- Page 310 and 311:

Kerry House 9 was located at the so

- Page 312 and 313:

Kerry Fig. 151: Plan of early medie

- Page 314 and 315:

Kerry to retain insulating sod for

- Page 316 and 317:

Kerry Fig. 152: Plan of Church Isla

- Page 318 and 319:

Kerry Clogher, Lixnaw, Co. Kerry Ea

- Page 320 and 321:

Kerry Cloghermore, Co. Kerry Cave G

- Page 322 and 323:

Kerry Many of the latest burials fr

- Page 324 and 325:

Kerry A.D. 912-970 Beta-137046 Huma

- Page 326 and 327:

Kerry Fig. 158: Plan of Coarhabeg c

- Page 328 and 329:

Kerry Fig. 159: Plan of Phase 1 hou

- Page 330 and 331:

Kerry ‘Dunbeg Fort’ (Fahan td.)

- Page 332 and 333:

Kerry A stone flagged path linked t

- Page 334 and 335:

Kerry Radiocarbon Dates: Sample No.

- Page 336 and 337:

Kerry inside and on top of the cist

- Page 338 and 339:

Kerry Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer

- Page 340 and 341:

Kerry House C was a rectangular bui

- Page 342 and 343:

Kerry Loher, Co. Kerry Early Mediev

- Page 344 and 345:

Kerry Reask, Co. Kerry Early Mediev

- Page 346 and 347:

Kerry was excavated within the inte

- Page 348 and 349:

Kerry Fig. 168: Plan of Reask, Co.

- Page 350 and 351:

Kerry References: Fanning, T. 1973.

- Page 352 and 353:

Kildare Killickaweeny, Co. Kildare

- Page 354 and 355:

Kildare Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reim

- Page 356 and 357:

Kildare Fig. 173: Prehistoric and e

- Page 358 and 359:

Kildare Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reim

- Page 360 and 361:

Kilkenny County Kilkenny Fig. 176:

- Page 362 and 363:

Kilkenny Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Rei

- Page 364 and 365:

Kilkenny ‘Kilkenny Castle’ (Duk

- Page 366 and 367:

Kilkenny ‘Leggetsrath’ (Blanchf

- Page 368 and 369:

Kilkenny Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Rei

- Page 370 and 371:

Kilkenny Radiocarbon Dates (PJ Reim

- Page 372 and 373:

Laois Parknahown, Co. Laois Early M

- Page 374 and 375:

Laois Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer

- Page 376 and 377:

Limerick Ballyduff, Co. Limerick Ea

- Page 378 and 379:

Limerick Ballynagallagh, Co. Limeri

- Page 380 and 381:

Limerick Fig. 185: Ditch and palisa

- Page 382 and 383:

Limerick Fig. 186: Plan of Carraig

- Page 384 and 385:

Limerick shade from light to dark-b

- Page 386 and 387:

Limerick The ‘Spectacles’ (Loug

- Page 388 and 389:

Limerick Coonagh West, Co. Limerick

- Page 390 and 391:

Limerick Croom East, Co. Limerick E

- Page 392 and 393:

Limerick Cush, Co. Limerick Early M

- Page 394 and 395:

Limerick house which utilized the t

- Page 396 and 397:

Limerick 4, Cush 6 and Cush 7 with

- Page 398 and 399:

Limerick The sites at Ballingoola (

- Page 400 and 401:

Limerick Knockea, Co. Limerick Earl

- Page 402 and 403:

Limerick Fig. 193: Plan of Phase 1

- Page 404 and 405:

Limerick about thirty). The last th

- Page 406 and 407:

Limerick Raheennamadra, Co. Limeric

- Page 408 and 409:

Limerick Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Rei

- Page 410 and 411:

Limerick Fig. 196: Plan of Sluggary

- Page 412 and 413:

Londonderry Big Glebe, Co. Londonde

- Page 414 and 415:

Londonderry Corrstown, Co. Londonde

- Page 416 and 417:

Londonderry Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ

- Page 418 and 419:

Londonderry Oughtymore, Co. Londond

- Page 420 and 421:

Longford County Longford Fig. 202:

- Page 422 and 423:

Longford Fig. 203: Excavated areas

- Page 424 and 425:

Louth County Louth Fig. 204: Signif

- Page 426 and 427:

Louth A stone-lined oval kiln, with

- Page 428 and 429:

Louth The north-eastern area within

- Page 430 and 431:

Louth O’Hara, R. 2009. Early medi

- Page 432 and 433:

Louth Delaney, S. 2010. An early me

- Page 434 and 435:

Louth made from bronze, iron and bo

- Page 436 and 437:

Louth Archaeological monitoring of

- Page 438 and 439:

Louth ‘Lissachiggel’, Doolargy,

- Page 440 and 441:

Louth Fig. 209: Detailed plan of ho

- Page 442 and 443:

Louth Archaeological investigations

- Page 444 and 445:

Louth central, L-shaped island of n

- Page 446 and 447:

Louth Fig. 212: Plan of Marshes Upp

- Page 448 and 449:

Louth Millockstown, Co. Louth Early

- Page 450 and 451:

Louth Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer

- Page 452 and 453:

Louth Fig. 214: Photograph of soute

- Page 454 and 455:

Mayo County Mayo Fig. 215: Signific

- Page 456 and 457:

Mayo Bofeenaun, Co. Mayo Early Medi

- Page 458 and 459:

Mayo Carrowkeel, Co. Mayo Early Med

- Page 460 and 461:

Mayo Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer,

- Page 462 and 463:

Mayo Fig. 219: Plan of ecclesiastic

- Page 464 and 465:

Mayo Letterkeen, Co. Mayo Early Med

- Page 466 and 467:

Mayo Fig. 222: Features near entran

- Page 468 and 469:

Mayo Fig. 223: Plan of excavated ar

- Page 470 and 471:

Mayo Moyne, Co. Mayo Early Medieval

- Page 472 and 473:

Meath County Meath Fig. 226: Signif

- Page 474 and 475:

Meath Fig. 227: Plan of excavations

- Page 476 and 477:

Meath Fig. 228: Plan of Augherskea,

- Page 478 and 479:

Meath possibly a foundation deposit

- Page 480 and 481:

Meath Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer

- Page 482 and 483:

Meath Betaghstown (Bettystown), Co.

- Page 484 and 485:

Meath Boolies Little, Co. Meath Ear

- Page 486 and 487:

Meath Castlefarm, Co. Meath Early M

- Page 488 and 489:

Meath Fig. 231: Enclosures at Castl

- Page 490 and 491:

Meath Cloncowan, Co. Meath Early Me

- Page 492 and 493:

Meath Collierstown 1, Co. Meath Ear

- Page 494 and 495:

Meath enclosure. This ditch contain

- Page 496 and 497:

Meath Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer

- Page 498 and 499:

Meath Fig. 234: Excavations at Colp

- Page 500 and 501:

Meath Fig. 235: Enclosures at Colp

- Page 502 and 503:

Meath Cormeen, Co. Meath Early Medi

- Page 504 and 505:

Meath bone and finds were few. The

- Page 506 and 507:

Meath Fig. 237: Phases of enclosure

- Page 508 and 509:

Meath Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer

- Page 510 and 511:

Meath Johnstown 1, Co. Meath Early

- Page 512 and 513:

Meath Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer

- Page 514 and 515:

Meath Knowth Site M, Co. Meath Earl

- Page 516 and 517:

Meath Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer

- Page 518 and 519:

Meath belt buckles, bone combs and

- Page 520 and 521:

Meath Lagore (Lagore Big td.), Co.

- Page 522 and 523:

Meath similar huge amounts being re

- Page 524 and 525:

Meath ‘Madden’s Hill’, Kiltal

- Page 526 and 527:

Meath Moynagh Lough, Co. Meath Earl

- Page 528 and 529:

Meath spreads of animal bone were u

- Page 530 and 531:

Meath Nevinstown, Co. Meath Early M

- Page 532 and 533:

Meath disturbed burial appeared to

- Page 534 and 535:

Meath layer of fire-reddened or bur

- Page 536 and 537:

Meath Kelly, E. P. 1981. A short st

- Page 538 and 539:

Meath suggests a network of trade a

- Page 540 and 541:

Meath Beta-196366 Bone from linear

- Page 542 and 543:

Meath Raystown, Co. Meath Early Med

- Page 544 and 545:

Meath former cereal-drying kiln. Th

- Page 546 and 547:

Meath Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reimer

- Page 548 and 549:

Meath Roestown 2, Co. Meath Early M

- Page 550 and 551:

Meath Fig. 248: Phases from Roestow

- Page 552 and 553:

Meath St. Anne’s Chapel (Randalst

- Page 554 and 555:

Meath Simonstown, Co. Meath Early M

- Page 556 and 557:

Monaghan County Monaghan Fig. 249:

- Page 558 and 559:

Monaghan have been used for storage

- Page 560 and 561:

Offaly ‘Ballinderry II’ (Ballyn

- Page 562 and 563:

Offaly pins (ninth/tenth century da

- Page 564 and 565:

Offaly Ballintemple, Co. Offaly Ear

- Page 566 and 567:

Offaly Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly Ear

- Page 568 and 569:

Offaly References: Boland, D. & O'S

- Page 570 and 571:

Roscommon Cloongownagh, Co. Roscomm

- Page 572 and 573:

Roscommon ‘Rathcroghan’, Co. Ro

- Page 574 and 575:

Roscommon Tulsk, Co. Roscommon Earl

- Page 576 and 577:

Sligo County Sligo Fig. 258: Signif

- Page 578 and 579:

Sligo Fig. 259: Post-built structur

- Page 580 and 581:

Sligo Inishmurray, Co. Sligo Early

- Page 582 and 583:

Sligo Knoxspark, Co. Sligo Early Me

- Page 584 and 585:

Sligo References: Mount, C. 1994:20

- Page 586 and 587:

Sligo Fig. 262: Outline plan of Mag

- Page 588 and 589:

Sligo ‘Rathtinaun’ (Lough Gara

- Page 590 and 591:

Sligo discs and 1 rotary quern. The

- Page 592 and 593:

Sligo Sroove (Lough Gara td.), Co.

- Page 594 and 595:

Tipperary County Tipperary Fig. 264

- Page 596 and 597:

Tipperary Fig. 265: Plan of Bowling

- Page 598 and 599:

Tipperary saw the building of the p

- Page 600 and 601:

Tipperary stones, apparently the bo

- Page 602 and 603:

Tipperary Killoran (31), Co. Limeri

- Page 604 and 605:

Tipperary Killoran 66, Co. Tipperar

- Page 606 and 607:

Tyrone County Tyrone Fig. 270: Sign

- Page 608 and 609:

Tyrone Fig. 272: Early medieval Pha

- Page 610 and 611:

Tyrone Fig. 273: Excavation plan of

- Page 612 and 613:

Tyrone Dunmisk, Co. Tyrone Early Me

- Page 614 and 615:

Tyrone Radiocarbon Dates: (PJ Reime

- Page 616 and 617:

Tyrone Fig. 276: Excavated area at

- Page 618 and 619:

Tyrone Mullaghbane, Co. Tyrone Earl

- Page 620 and 621:

Waterford County Waterford Fig. 280

- Page 622 and 623:

Waterford Kilgreany, Co. Waterford

- Page 624 and 625:

Waterford Fig. 282: Plan of Kilgrea

- Page 626 and 627:

Waterford Kill St. Lawrence, Co. Wa

- Page 628 and 629:

Waterford ‘Kiltera’ (Dromore td

- Page 630 and 631:

Waterford Fig. 283: Plan of Kiltera

- Page 632 and 633:

Waterford Little Patrick Street/Bar

- Page 634 and 635:

Waterford Ireland and took up at Po

- Page 636 and 637:

Waterford There is very little tent

- Page 638 and 639:

Waterford eastern half of the earli

- Page 640 and 641:

Waterford Though the archaeological

- Page 642 and 643:

Waterford Wren 1993 & 1998), the va

- Page 644 and 645:

Waterford By the early thirteenth c

- Page 646 and 647:

Waterford Fig. 291: Excavated build

- Page 648 and 649:

Waterford Fragmentary structural re

- Page 650 and 651:

Waterford Large amounts of antler a

- Page 652 and 653:

Waterford Hurley, M.F. 1990:108. Ar

- Page 654 and 655:

Waterford McCutcheon, S. W. J. & Hu

- Page 656 and 657:

Waterford Wallace, P. F. 2005. The

- Page 658 and 659:

Waterford A stone metalled entrance

- Page 660 and 661:

Waterford It has been suggested tha

- Page 662 and 663:

Waterford References: Eogan, J. 200

- Page 664 and 665:

Westmeath Ballinderry I, Co. Westme

- Page 666 and 667:

Westmeath rectangular house, as the

- Page 668 and 669:

Westmeath Clonfad, Co. Westmeath Ea

- Page 670 and 671:

Westmeath Kilpatrick, Killucan, (Co

- Page 672 and 673:

Westmeath Newtownlow, Co. Westmeath

- Page 674 and 675:

Westmeath Rochfort Demesne, Co. Wes

- Page 676 and 677:

Westmeath Togherstown, Co. Westmeat

- Page 678 and 679:

Westmeath Fig. 300: Plan of enclosu

- Page 680 and 681:

Wexford Bride Street, Wexford, Co.

- Page 682 and 683:

Wicklow Giltspur, Co. Wicklow Early

- Page 685:

UCD School of Archaeology