Proceedings of the European Summer School of Photovoltaics 4 â 7 ...

Proceedings of the European Summer School of Photovoltaics 4 â 7 ...

Proceedings of the European Summer School of Photovoltaics 4 â 7 ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Conclusions<br />

There are many types <strong>of</strong> organic and organic/inorganic (hybrid)<br />

photovoltaic devices that possess many beneficial properties over<br />

inorganic solar cells. That makes <strong>the</strong> former suitable for a broad<br />

range <strong>of</strong> applications and hence so much attention is paid to <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

development. In spite <strong>of</strong> intensive research carried on this field<br />

<strong>of</strong> science and technology <strong>the</strong>re are still many crucial problems<br />

that need to be solved. Extensive knowledge on physical basis<br />

<strong>of</strong> operation <strong>of</strong> organic and hybrid systems, fast development <strong>of</strong><br />

nanotechnology, great variety <strong>of</strong> organic materials and methods<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir modification will pave <strong>the</strong> way for commercial applications<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se devices.<br />

References<br />

[1] Toward a Just and Sustainable Solar Energy Industry, A Silicon Valley<br />

Toxics Coalition White Paper, January 14, 2009.<br />

[2] Brabec Ch. J.: “Organic photovoltaics: technology and market”, Solar<br />

Energy Materials & Solar Cells, 83 (2004), 273-292.<br />

[3] Jorgensen M., K. Norrman, F. C. Krebs: “Stability/degradation <strong>of</strong><br />

polymer solar cells”, Solar Energy Materials & Solar Cells 92 (2008)<br />

686–714.<br />

[4] Clarke T. M., J. R. Durrant: “Charge photogeneration in organic solar<br />

cells”, Chemical Review 110 (2010) 6736–6767.<br />

[5] Scharber M. C., D. Muhlbacher, M. Koppe, P. Denk, C. Waldauf, A. J.<br />

Heeger, C. J. Brabec: Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 789–794.<br />

[6] Kinoshita Y., R. Takenaka, H. Murata: “Independent control <strong>of</strong> opencircuit<br />

voltage <strong>of</strong> organic solar cells by changing film thickness <strong>of</strong><br />

MoO3 buffer layer “, Appl. Phys. Lett. 92 (2008), 243309-1-3.<br />

[7] Kim D.Y., G. Sarasquerta, and F. So: “SnPc:C60 bulk hetero−junction<br />

organic photovoltaic cells with MoO3 interlayer”, Sol. Energ. Mat. Sol.<br />

C93 (2009), 1452–1456.<br />

[8] Vogel M., S. Doka, Ch. Breyer, M.Ch. Lux−Steiner, and K.Festiropoulos:<br />

“On <strong>the</strong> function <strong>of</strong> a bathocuproine buffer layer in organic photovoltaic<br />

cells”, Appl. Phys. Lett. 89 (2006), 163501−1−3.<br />

[9] Gommans H., B. Verreet, B.P. Rand, R. Muller, J. Poortmans, P. Heremans<br />

and J. Genoe: “On <strong>the</strong> Role <strong>of</strong> Bathocuproine in Organic Photovoltaic<br />

Cells”, Adv. Funct. Mater. 18 (2008), 3686–3691.<br />

[10] Signerski R., G. Jarosz: “Effect <strong>of</strong> buffer layers on performance <strong>of</strong> organic<br />

photovoltaic devices based on copper phthalocyanine – perylene<br />

dye heterojunction”, Opto−Electron. Rev. 19 (2011), 468–473.<br />

[11] Signerski R., G. Jarosz, B. Kościelska: “Photovoltaic effect in hybrid<br />

heterojunction formed from cadmium telluride and zinc perfluorophthalocyanine<br />

layers”, J. Non- Cryst. Sol. 356 (2010), 2053–2055.<br />

[12] Signerski R., G. Jarosz, B. Kościelska: “On photovoltaic effect in hybrid<br />

heterojunction formed from palladium phthalocyanine and titanium<br />

dioxide layers, J. Non-Cryst. Sol. 355 (2009), 1405–1407.<br />

[13] Signerski R., B. Kościelska: “Photovoltaic properties <strong>of</strong> a sandwich<br />

cell consisting <strong>of</strong> bromophosphorus phthalocyanine and titanium dioxide<br />

layers”, Opt. Mat. 27 (2005), 1480–1483.<br />

[14] Rowell M.W., M.A. Topinka, M.D. McGehee, H.J. Prall, G. Dennler,<br />

N.S. Sariciftici, L. Hu, G. Gruner: Appl. Phys. Lett. 88 (2006) 233506-<br />

1-233506-3.<br />

[15] Chaudhary S., H. Lu, A.M. Muller, C.J. Bardeen, M. Ozkan: Nano<br />

Lett. 7 (2007) 1973–1979.<br />

[16] Pradhan B., S.K. Batabyal, A.J. Pal.: Appl. Phys. Lett. 88 (2006)<br />

093106-1- 093106-3.<br />

[17] Kymakis E., P. Servati, P. Tzanetakis, E. Koudoumas, N. Kornilios, I.<br />

Rompogiannakis, Y. Franghiadakis, G.A.J. Amaratunga: Nanotechnology<br />

18 (2007) 435702/1–435702/6.<br />

[18] Reyes-Reyes M., R. Lopez-Sandoval, J. Liu, D.L. Carroll: Sol. Energy<br />

Mat. Sol. Cells 91 (2007) 1478–1482.<br />

[19] Previti F., S. Patane, M. Allegrini: Appl. Surf. Sci. 255 (2009) 9877–<br />

9879.<br />

[20] Singh I., P.K. Bhatnagar, P.C. Mathur, I. Kaur, L.M. Bharadwaj, R.<br />

Pandey: Carbon 46 (2008) 1141–1144.<br />

[21] Rastogi R., R. Kaushal, S.K. Tripathi, A. L. Sharma, I.Kaur, L. M.<br />

Bharadwaj: J. Coll. Interf. Sci. 328 (2008) 421–428.<br />

[22] Nogueira A.F., B. S. Lomba, M. A. Soto-Oviedo, C. R. D. Correia: J.<br />

Phys. Chem. C 49 (2007), 18431–18438.<br />

[23] Stylianakis M. M., J. A. Mikroyannidis, E. Kymakis: Sol. Energy Mat.<br />

Sol. Cells 94 (2010) 267–274.<br />

[24] Jubete E., K. Żelechowska, O. A. Loaiza, P. J. Lamas, E. Ochoteco,<br />

K. D. Farmer, K. P. Roberts, J. F. Biernat: Electrochim. Acta 56<br />

(2011) 3988–3995.<br />

[25] Sadowska K. (Żelechowska), J. F. Biernat, K. Stolarczyk, R. Bilewicz,<br />

K. Roberts, J. Rogalski: Bioelectrochem. 80(1) (2010) 73–80.<br />

[26] Sadowska K. (Żelechowska), K.P. Roberts, R. Wiser, J.F. Biernat, E.<br />

Jabłonowska and R. Bilewicz: Carbon 47 (2009) 1501–1510.<br />

Surface morphology and optical properties<br />

<strong>of</strong> polymer thin films<br />

JAN Weszka 1,2) , Magdalena Szindler 1,4) , Maria Bruma 3)<br />

1)<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Engineering Materials and Biomaterials, Silesian University <strong>of</strong> Technology,Gliwice, Poland<br />

2)<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Physics, Center <strong>of</strong> Polymer and Carbon Materials, Polish Academy <strong>of</strong> Sciences,Zabrze, Poland<br />

3)<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Macromolecular Chemistry,Romania, 4) Corresponding author<br />

Industrial development has always been associated with <strong>the</strong> development<br />

<strong>of</strong> energy technologies, mainly consisted <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> introduction<br />

<strong>of</strong> changes to <strong>the</strong> existing and implementing new types<br />

<strong>of</strong> energy sources. In <strong>the</strong> twentieth century, <strong>the</strong>se changes consisted<br />

mainly in <strong>the</strong> transition from coal as <strong>the</strong> primary energy<br />

fuel for petroleum and <strong>the</strong>n from oil to gas. Today, <strong>the</strong> economic<br />

and ecological reasons, looking for alternative sources <strong>of</strong> energy.<br />

Seems to be <strong>the</strong> most valuable comes from renewable sources<br />

and can be converted to any form <strong>of</strong> energy. The rapid development<br />

<strong>of</strong> electronics and materials science, and especially for semiconductor<br />

and chemistry <strong>of</strong> polymeric materials is related to <strong>the</strong><br />

introduction <strong>of</strong> modern engineering materials. Gained important<br />

conductive polymers [1, 2].<br />

The most famous <strong>of</strong> conductive polymer materials include<br />

polyacetylene, polythiophene, and polyphenylene. An important<br />

group <strong>of</strong> polymers whose main chains are composed<br />

<strong>of</strong> carbon atoms connected by alternating single and double<br />

bonds, called conjugated polymers. Conjugated polymers can<br />

be used in photovoltaic and optoelectronics. This group includes<br />

polyoxadiazoles. Conductive polymers <strong>of</strong>ten show a conductivity<br />

only slightly worse than <strong>the</strong> most conductive metals<br />

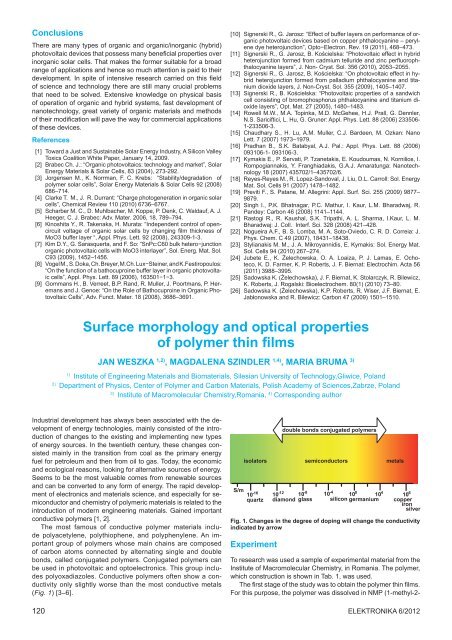

(Fig. 1) [3–6].<br />

120<br />

isolators semiconductors metals<br />

S/m<br />

10<br />

-16<br />

quartz<br />

Experiment<br />

double bonds conjugated polymers<br />

10 -12<br />

diamond 10-8<br />

glass<br />

10 -4 silicon 100<br />

germanium 104 10 6<br />

copper<br />

iron<br />

silver<br />

Fig. 1. Changes in <strong>the</strong> degree <strong>of</strong> doping will change <strong>the</strong> conductivity<br />

indicated by arrow<br />

To research was used a sample <strong>of</strong> experimental material from <strong>the</strong><br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Macromolecular Chemistry, in Romania. The polymer,<br />

which construction is shown in Tab. 1, was used.<br />

The first stage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study was to obtain <strong>the</strong> polymer thin films.<br />

For this purpose, <strong>the</strong> polymer was dissolved in NMP (1-methyl-2-<br />

Elektronika 6/2012