1qGLG9p

1qGLG9p

1qGLG9p

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

68 Deleveraging, What Deleveraging<br />

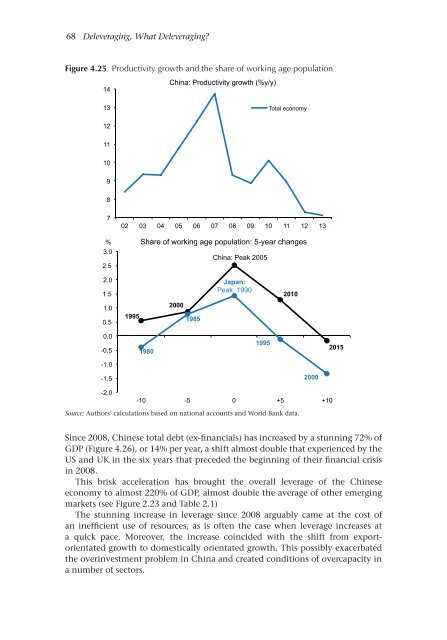

Figure 4.25 Productivity growth and the share of working age population<br />

14<br />

China: Productivity growth (%y/y)<br />

13<br />

Total economy<br />

12<br />

11<br />

10<br />

9<br />

8<br />

7<br />

02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13<br />

% Share of working age population: 5-year changes<br />

3.0<br />

China: Peak 2005<br />

2.5<br />

2.0<br />

1.5<br />

Japan:<br />

Peak: 1990<br />

2010<br />

1.0<br />

0.5<br />

1995<br />

2000<br />

1985<br />

0.0<br />

-0.5<br />

1980<br />

1995<br />

2015<br />

-1.0<br />

-1.5<br />

-2.0<br />

2000<br />

-10 -5 0 +5 +10<br />

Source: Authors’ calculations based on national accounts and World Bank data.<br />

Since 2008, Chinese total debt (ex-financials) has increased by a stunning 72% of<br />

GDP (Figure 4.26), or 14% per year, a shift almost double that experienced by the<br />

US and UK in the six years that preceded the beginning of their financial crisis<br />

in 2008.<br />

This brisk acceleration has brought the overall leverage of the Chinese<br />

economy to almost 220% of GDP, almost double the average of other emerging<br />

markets (see Figure 2.23 and Table 2.1)<br />

The stunning increase in leverage since 2008 arguably came at the cost of<br />

an inefficient use of resources, as is often the case when leverage increases at<br />

a quick pace. Moreover, the increase coincided with the shift from exportorientated<br />

growth to domestically orientated growth. This possibly exacerbated<br />

the overinvestment problem in China and created conditions of overcapacity in<br />

a number of sectors.