You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

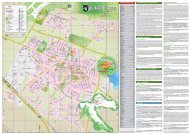

central castello<br />

|<br />

162<br />

Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo<br />

that <strong>the</strong>y were usually built on <strong>the</strong> edges of city centres. In <strong>Venice</strong> <strong>the</strong> various<br />

mendicant orders are scattered outside <strong>the</strong> San Marco sestiere: <strong>the</strong> Dominicans<br />

here, <strong>the</strong> Franciscans at <strong>the</strong> Frari <strong>and</strong> San Francesco della Vigna, <strong>the</strong> Carmelites<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Carmini <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Servites at Santa Maria dei Servi. (<strong>The</strong> dedicatees<br />

of <strong>the</strong> church, by <strong>the</strong> way, are not <strong>the</strong> apostles John <strong>and</strong> Paul, but instead a pair<br />

of probably fictional saints whose s<strong>to</strong>ry seems <strong>to</strong> be derived from that of saints<br />

Juventinus <strong>and</strong> Maximinius, who were martyred during <strong>the</strong> reign of Julian <strong>the</strong><br />

Apostate, in <strong>the</strong> fourth century.)<br />

<strong>The</strong> first church built on this site was begun in 1246 after Doge Giacomo<br />

Tiepolo was inspired by a dream <strong>to</strong> donate <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dominicans – he<br />

dreamed that a flock of white doves, each marked on its forehead with <strong>the</strong> sign<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Cross, had flown over <strong>the</strong> swampl<strong>and</strong> where <strong>the</strong> church now st<strong>and</strong>s, as<br />

a celestial voice in<strong>to</strong>ned “I have chosen this place for my ministry” (<strong>the</strong> scene<br />

is depicted in <strong>the</strong> sacristy). That initial version was soon demolished <strong>to</strong> make<br />

way for this larger building, begun in 1333, though not consecrated until<br />

1430. Tiepolo’s simple sarcophagus is outside, on <strong>the</strong> left of <strong>the</strong> door, next<br />

<strong>to</strong> that of his son Doge Lorenzo Tiepolo (d.1275); both <strong>to</strong>mbs were altered<br />

after <strong>the</strong> Bajamonte Tiepolo revolt of 1310 (see p.391), when <strong>the</strong> family was<br />

no longer allowed <strong>to</strong> display its old crest <strong>and</strong> had <strong>to</strong> devise a replacement.<br />

<strong>The</strong> doorway, flanked by Byzantine reliefs, is thought <strong>to</strong> be by Bar<strong>to</strong>lomeo<br />

Bon, <strong>and</strong> is one of <strong>the</strong> major transitional Gothic-Renaissance works in <strong>the</strong><br />

city; apart from that, <strong>the</strong> most arresting architectural feature of <strong>the</strong> exterior<br />

is <strong>the</strong> complex brickwork of <strong>the</strong> apse. <strong>The</strong> Cappella di Sant’Orsola (closed),<br />

between <strong>the</strong> door <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> right transept <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> apse, is where <strong>the</strong> two Bellini<br />

bro<strong>the</strong>rs are buried; it used <strong>to</strong> house <strong>the</strong> Scuola di Sant’Orsola, <strong>the</strong> confraternity<br />

which commissioned from Carpaccio <strong>the</strong> St Ursula cycle now installed in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Accademia.<br />

<strong>The</strong> simplicity of <strong>the</strong> cavernous interior – approximately 90m long, 38m<br />

wide at <strong>the</strong> transepts, 33m high in <strong>the</strong> centre – is offset by Zanipolo’s profusion<br />

of <strong>to</strong>mbs <strong>and</strong> monuments, including those of some 25 doges.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Mocenigo <strong>to</strong>mbs <strong>and</strong> south aisle<br />

<strong>The</strong> only part of <strong>the</strong> entrance wall that isn’t given over <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> glorification<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Mocenigo family is <strong>the</strong> monument <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> poet Bar<strong>to</strong>lomeo Bragadin,<br />

which happened <strong>to</strong> be <strong>the</strong>re first. It’s now engulfed by <strong>the</strong> monument <strong>to</strong><br />

Doge Alvise Mocenigo <strong>and</strong> his wife (1577) which wraps itself round <strong>the</strong><br />

doorway; on <strong>the</strong> right is Tullio Lombardo’s monument <strong>to</strong> Doge Giovanni<br />

Mocenigo (d.1485); <strong>and</strong> on <strong>the</strong> left is <strong>the</strong> superb monument <strong>to</strong> Doge Pietro<br />

Mocenigo (d.1476), by Pietro Lombardo, with assistance from Tullio <strong>and</strong><br />

An<strong>to</strong>nio. Pietro Mocenigo’s sarcophagus, supported by warriors representing<br />

<strong>the</strong> three Ages of Man, is embellished with a Latin inscription (Ex Hostium<br />

Manibus – “From <strong>the</strong> h<strong>and</strong>s of <strong>the</strong> enemy”) pointing out that <strong>the</strong> spoils of war<br />

paid for his <strong>to</strong>mb, <strong>and</strong> a couple of reliefs showing his valorous deeds, including<br />

<strong>the</strong> h<strong>and</strong>ing of <strong>the</strong> keys of Famagusta <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> doomed Caterina Cornaro<br />

(see p.372).<br />

To <strong>the</strong> left of <strong>the</strong> first altar of <strong>the</strong> right aisle is <strong>the</strong> monument <strong>to</strong> Marcan<strong>to</strong>nio<br />

Bragadin, <strong>the</strong> central figure in one of <strong>the</strong> grisliest episodes in <strong>Venice</strong>’s<br />

his<strong>to</strong>ry. <strong>The</strong> comm<strong>and</strong>er of <strong>the</strong> Venetian garrison at Famagusta during <strong>the</strong><br />

Turkish siege of 1571, Bragadin marshalled a resistance which lasted eleven<br />

months until, with his force reduced from 7000 men <strong>to</strong> 700, he was obliged<br />

<strong>to</strong> sue for peace. Given guarantees of safety, <strong>the</strong> Venetian officers entered <strong>the</strong><br />

enemy camp, whereupon most were dragged away <strong>and</strong> cut <strong>to</strong> pieces, whilst