- Page 1 and 2:

ROUGHGUIDES THE ROUGH GUIDE to Veni

- Page 3:

The Rough Guide to Venice & the Ven

- Page 6 and 7:

| IntRODUCTION | WHERE TO GO | WHEN

- Page 8 and 9:

| INTRODUCTION | WHERE to GO | WHEN

- Page 10 and 11:

| INTRODUCTION | WHERE to GO | WHEN

- Page 12 and 13:

| INTRODUCTION | WHERE TO GO | WHen

- Page 14 and 15:

| consUME | EVents | SIGHTS | The G

- Page 16 and 17:

| consUME | EVents | SIGHTS | Ciche

- Page 18 and 19:

| consUME | EVents | SIGHTS | The M

- Page 20 and 21:

Basics Getting there ..............

- Page 22 and 23:

BASICS | Getting there 20 Christmas

- Page 24 and 25:

BASICS | Getting there 22 if you tr

- Page 26 and 27:

BASICS | The media Airlines in Aust

- Page 28 and 29:

BASICS | Travel essentials of model

- Page 30 and 31:

BASICS | Travel essentials 28 probl

- Page 32 and 33:

BASICS | Travel essentials 30 and i

- Page 34 and 35:

BASICS | Travel essentials includin

- Page 36 and 37:

The City Venice: the practicalities

- Page 38 and 39:

36 venice: the Practicalities | San

- Page 40 and 41:

38 venice: the Practicalities | Wat

- Page 42 and 43:

7.50pm); San Marcuola-Fondaco dei T

- Page 44 and 45:

Frari Mon-Sat 9am-6pm, Sun 1-6pm; e

- Page 46 and 47:

san marco The Piazza | 44

- Page 48 and 49:

san marco | The Piazza 46 orchard o

- Page 50 and 51:

san marco | The Basilica di San Mar

- Page 52 and 53:

san marco | 50 The Basilica di San

- Page 54 and 55:

san marco | 52 The Basilica di San

- Page 56 and 57:

san marco | 54 The Basilica di San

- Page 58 and 59:

san marco | 56 The Basilica di San

- Page 60 and 61:

san marco | 58 The Basilica di San

- Page 62 and 63:

san marco | The Palazzo Ducale 60 A

- Page 64 and 65:

The Government of Venice san marco

- Page 66 and 67:

in as to how much of the building i

- Page 68 and 69:

san marco | 66 The Palazzo Ducale o

- Page 70 and 71:

san marco | 68 The Palazzo Ducale o

- Page 72 and 73:

san marco | The Campanile and the C

- Page 74 and 75:

The Bicentenary Siege san marco | T

- Page 76 and 77:

san marco | 74 The Procuratie a dev

- Page 78 and 79:

san marco | The Piazzetta and the M

- Page 80 and 81:

san marco | North of the Piazza him

- Page 82 and 83:

san marco | 80 North of the Piazza

- Page 84 and 85:

san marco | 82 North of the Piazza

- Page 86 and 87:

san marco | 84 North of the Piazza

- Page 88 and 89:

san marco West of the Piazza | 86

- Page 90 and 91:

The 1996 Fenice fire san marco | 88

- Page 92 and 93:

san marco | West of the Piazza 90

- Page 94 and 95:

san marco | 92 West of the Piazza b

- Page 96 and 97:

2 Dorsoduro dorsoduro There | were

- Page 98 and 99:

dorsoduro | 96 The Accademia - but

- Page 100 and 101:

dorsoduro | 98 The Accademia 1560s)

- Page 102 and 103:

The street cuts down almost as far

- Page 104 and 105:

dorsoduro | 102 Eastern Dorsoduro R

- Page 106 and 107:

dorsoduro | 104 The Záttere and we

- Page 108 and 109:

dorsoduro | Northern Dorsoduro by o

- Page 110 and 111:

dorsoduro | 108 Northern Dorsoduro

- Page 112 and 113:

dorsoduro | 110 Northern Dorsoduro

- Page 114 and 115:

dorsoduro | Northern Dorsoduro Gian

- Page 116 and 117:

Carnevale John Evelyn wrote of the

- Page 118 and 119:

The Regata Storica Held on the firs

- Page 120 and 121:

San Polo and Santa Croce | From the

- Page 122 and 123:

San Polo and Santa Croce | From the

- Page 124 and 125:

San Polo and Santa Croce | From the

- Page 126 and 127:

San Polo and Santa Croce | 120 From

- Page 128 and 129:

San Polo and Santa Croce | 122 From

- Page 130 and 131:

San Polo and Santa Croce | 124 From

- Page 132 and 133:

Aldus Manutius San Polo and Santa C

- Page 134 and 135:

San Polo and Santa Croce | 128 From

- Page 136 and 137:

Christ by Vittoria, and a Virgin an

- Page 138 and 139:

San Polo and Santa Croce | 132 From

- Page 140 and 141:

San Polo and Santa Croce | 134 From

- Page 142 and 143:

San Polo and Santa Croce | 136 From

- Page 144 and 145:

4 Cannaregio | From the train stati

- Page 146 and 147:

Cannaregio | From the train station

- Page 148 and 149:

paintings in Venice that is compara

- Page 150 and 151:

Cannaregio The Ghetto | 144 The Gh

- Page 152 and 153:

Cannaregio | 146 Northern Cannaregi

- Page 154 and 155:

to the chapel containing Tintoretto

- Page 156 and 157:

Cannaregio | 150 Southern and easte

- Page 158 and 159:

city. Those who haven’t acquired

- Page 160 and 161:

Cannaregio Southern and eastern Can

- Page 162 and 163:

The Fondamente Nove The long waterf

- Page 164 and 165:

5 Central Castello central castello

- Page 166 and 167:

central castello Campo Santi Giovan

- Page 168 and 169:

central castello | 162 Campo Santi

- Page 170 and 171:

central castello | 164 Campo Santi

- Page 172 and 173:

central castello | 166 Campo Santi

- Page 174 and 175:

order the square, the most impressi

- Page 176 and 177:

central castello | 170 Campo Santa

- Page 178 and 179:

central castello | 172 San Zaccaria

- Page 180 and 181:

central castello | 174 San Zaccaria

- Page 182 and 183:

central castello | San Zaccaria to

- Page 184 and 185:

eastern castello | San Francesco de

- Page 186 and 187:

eastern castello | 180 San Francesc

- Page 188 and 189:

white dog in the final one. The sce

- Page 190 and 191:

Follow the fondamenta south from Sa

- Page 192 and 193:

a less precisely classical storey -

- Page 194 and 195:

statue of Admiral Angelo Emo (1792)

- Page 196 and 197:

eastern castello | Beyond the Arsen

- Page 198 and 199:

the canal grande | The Left Bank 19

- Page 200 and 201:

the canal grande The Left Bank | 19

- Page 202 and 203:

the canal grande | 196 The Left Ban

- Page 204 and 205:

the canal grande | The Right Bank s

- Page 206 and 207:

the canal grande | 200 The Right Ba

- Page 208 and 209:

From the Ca’ Rezzonico to the Dog

- Page 210 and 211:

the canal grande | The Right Bank r

- Page 212 and 213:

the northern islands San Michele |

- Page 214 and 215:

the highest funeral honour the city

- Page 216 and 217:

Venetian glass the northern islands

- Page 218 and 219:

the northern islands | 212 Burano a

- Page 220 and 221:

the northern islands | Torcello the

- Page 222 and 223:

Saint Fosca, brought to Torcello fr

- Page 224 and 225:

draws thousands of people to its be

- Page 226 and 227:

gatekeeper might do the trick if he

- Page 228 and 229:

the southern islands | La Giudecca

- Page 230 and 231:

Damiano, having been left to crumbl

- Page 232 and 233:

and southern ends of the island - t

- Page 234 and 235:

the southern islands | 228 From the

- Page 236 and 237:

the southern islands | 230 San Lazz

- Page 238 and 239:

can now be seen. Lazzaretto Vecchio

- Page 240 and 241:

Listings 10 Accommodation 235-248 1

- Page 242 and 243:

236 accommodation | Hotels Hotels V

- Page 244 and 245:

238 accommodation | Hotels Santo St

- Page 246 and 247:

240 accommodation | Hotels San Cass

- Page 248 and 249:

the continent - provided you book a

- Page 250 and 251:

244 accommodation | Hotels Sant’A

- Page 252 and 253:

accommodation Bed & Breakfast • S

- Page 254 and 255:

per night on average. They take boo

- Page 256 and 257:

isn’t a Venetian speciality. Take

- Page 258 and 259:

252 Eating and drinking | Restauran

- Page 260 and 261:

Eating and drinking | Restaurants 2

- Page 262 and 263:

256 Eating and drinking | Restauran

- Page 264 and 265:

Methods and materials One of the at

- Page 266 and 267:

h Ca’ Pèsaro The floor plan Vene

- Page 268 and 269:

evening & all Tues. Moderate. Da Re

- Page 270 and 271:

Eating and drinking Bars and snacks

- Page 272 and 273:

Late-night drinking The following p

- Page 274 and 275:

Eating and drinking Bars and snacks

- Page 276 and 277:

Eating and drinking Cafés, pasticc

- Page 278 and 279:

Santa Margherita, Campiello dell’

- Page 280 and 281:

nightlife and the arts Music and th

- Page 282 and 283:

joint called Club Malvasia Vecchia

- Page 284 and 285:

nightlife and the arts | Other exhi

- Page 286 and 287:

Margherita 2928. Mon-Fri 8am-1pm &

- Page 288 and 289:

shopping Glass • Jewellery | boat

- Page 290 and 291:

shopping | Masks Ca’ Macana 280

- Page 292 and 293:

an interesting line in personalized

- Page 294 and 295:

Directory | 284 Giovanni e Paolo, t

- Page 297 and 298:

The Veneto 287

- Page 299 and 300:

The Veneto: practicalities The admi

- Page 301 and 302:

ments - which sometimes means no se

- Page 303 and 304:

L Padua and the southern Veneto Sum

- Page 305 and 306:

Hoi polloi can get to Malcontenta f

- Page 307 and 308:

and the dining room has a ceiling f

- Page 309 and 310:

of the twelfth century, when it bec

- Page 311 and 312:

This is the nearest campsite to Pad

- Page 313 and 314:

century works, including four myste

- Page 315 and 316:

Menabuoi have survived. Most of the

- Page 317 and 318:

Monument to Gattamelata decorated c

- Page 319 and 320:

and 1577, they are the most importa

- Page 321 and 322:

ut the vast Saturday market, groups

- Page 323 and 324:

season’s events can be obtained f

- Page 325 and 326:

From the train station, the route t

- Page 327 and 328:

train ride from Monsélice (9 daily

- Page 329 and 330:

Walls of Montagnana Practicalities

- Page 331 and 332:

is La Rotonda (April-Oct daily 8am-

- Page 333 and 334:

A few of these villas are of intere

- Page 335 and 336:

Bèrico; the downside is that it’

- Page 337 and 338:

Andrea Palladio Born in Padua in 15

- Page 339 and 340:

finished until the second decade of

- Page 341 and 342:

Palladio’s rugged Palazzo Thiene,

- Page 343 and 344:

ers in 899 and then by earthquakes

- Page 345 and 346:

in Rome in the service of the papac

- Page 347 and 348:

Montecchio’s other attractions, a

- Page 349 and 350: From the main train station (Verona

- Page 351 and 352: Vicenza, Verona and around | Verona

- Page 353 and 354: Combined tickets A biglietto unico,

- Page 355 and 356: in a room off the courtyard of the

- Page 357 and 358: loody feuds being commonplace (the

- Page 359 and 360: Its large rose window, representing

- Page 361 and 362: For a non-alcoholic indulgence, sit

- Page 363 and 364: Listings American Express c/o H.P.T

- Page 365 and 366: Treviso today is a brisk commercial

- Page 367 and 368: dressing stone led in the thirteent

- Page 369 and 370: Agnes and John by Tomaso himself, o

- Page 371 and 372: (t0422.411.661, wwww.hotelcarlton.i

- Page 373 and 374: at Borgo Treviso 73, opposite the t

- Page 375 and 376: century mistakes. It’s better kno

- Page 377 and 378: the bridge in 1948). The river was

- Page 379 and 380: The Town Maróstica was run by the

- Page 381 and 382: The Gipsoteca and Casa Canova The p

- Page 383 and 384: The Town The main road into town fr

- Page 385 and 386: Venetians who were then beginning t

- Page 387 and 388: to some it was Castaldi rather than

- Page 389 and 390: Cima exemplifies the conservative s

- Page 391 and 392: Oct-April 9.30am-12.30pm & 2-5pm; e

- Page 393 and 394: (named after a group of partisans e

- Page 395 and 396: Contexts 385

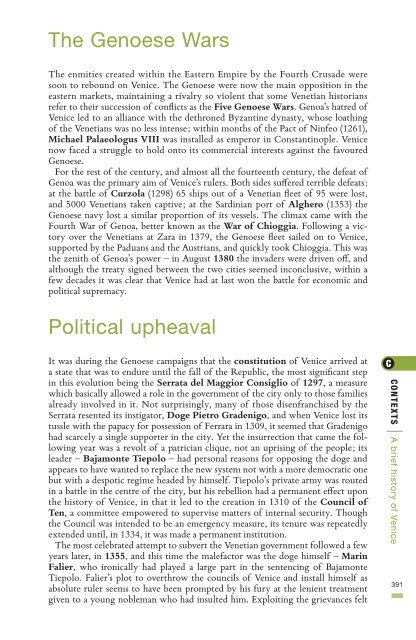

- Page 397 and 398: A brief history of Venice In the mi

- Page 399: Antonio Venier 1382-1400 Michele St

- Page 403 and 404: and the new ruler of Milan, Frances

- Page 405 and 406: No sooner was the Interdict out of

- Page 407 and 408: works of art. The Austrians’ urba

- Page 409 and 410: airport and Mestre. Apologists for

- Page 411 and 412: Greco (1545-1614) worked with the M

- Page 413 and 414: High Renaissance painting While the

- Page 415 and 416: Malipiero, is pictorially flat and

- Page 417 and 418: An outline of Venetian architecture

- Page 419 and 420: San Zanipolo (Dominican) and the Fr

- Page 421 and 422: death of Bartolomeo Bon in 1529, a

- Page 423 and 424: church of this period - San Simeone

- Page 425 and 426: ebuilt, reintroducing industry and

- Page 427 and 428: have been extended within a grid of

- Page 429 and 430: inside and excreting white crusts o

- Page 431 and 432: Romanticism. Lots of passion and pa

- Page 433 and 434: choice of pictures are exemplary. A

- Page 435 and 436: to the history of Venice between th

- Page 437 and 438: series of itineraries of the city f

- Page 439 and 440: Language 429

- Page 441 and 442: Language Although it’s not uncomm

- Page 443 and 444: Numbers 1 uno 2 due 3 tre 4 quattro

- Page 445 and 446: In the restaurant A table I’d lik

- Page 447 and 448: Pasta Cannelloni Farfalle Fettucine

- Page 449 and 450: Pecorino Provolone Ricotta Strong-t

- Page 451 and 452:

Glossary of Italian words Italian w

- Page 453 and 454:

Travel store

- Page 455:

Travel store

- Page 462 and 463:

A Rough Guide to Rough Guides Publi

- Page 464 and 465:

Acknowledgements and readers’ let

- Page 466 and 467:

index | 456 Campo Santi Giovanni e

- Page 468 and 469:

index | 458 Luzzo, Lorenzo.........

- Page 470 and 471:

index | 460 Pisanello.......152, 34

- Page 472 and 473:

index | 462 Tiepolo, Doge Giacomo..

- Page 474:

Map symbols maps are listed in the