II. - Schloss Schwetzingen

II. - Schloss Schwetzingen

II. - Schloss Schwetzingen

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>II</strong>.<br />

48<br />

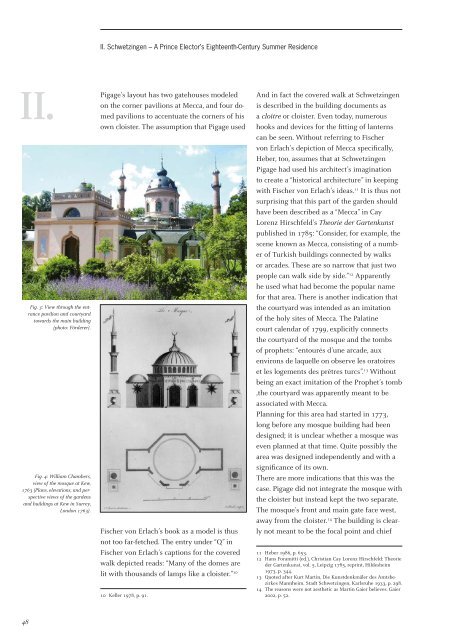

Fig. 3: View through the entrance<br />

pavilion and courtyard<br />

towards the main building<br />

(photo: Förderer).<br />

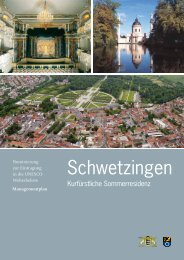

Fig. 4: William Chambers,<br />

view of the mosque at Kew,<br />

1763 (Plans, elevations, and perspective<br />

views of the gardens<br />

and buildings at Kew in Surrey,<br />

London 1763).<br />

<strong>II</strong>. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – A Prince Elector’s Eighteenth-Century Summer Residence<br />

Pigage’s layout has two gatehouses modeled<br />

on the corner pavilions at Mecca, and four domed<br />

pavilions to accentuate the corners of his<br />

own cloister. The assumption that Pigage used<br />

Fischer von Erlach’s book as a model is thus<br />

not too far-fetched. The entry under “Q” in<br />

Fischer von Erlach’s captions for the covered<br />

walk depicted reads: “Many of the domes are<br />

lit with thousands of lamps like a cloister.” 10<br />

10 Keller 1978, p. 91.<br />

And in fact the covered walk at <strong>Schwetzingen</strong><br />

is described in the building documents as<br />

a cloître or cloister. Even today, numerous<br />

hooks and devices for the fi tting of lanterns<br />

can be seen. Without referring to Fischer<br />

von Erlach’s depiction of Mecca specifi cally,<br />

Heber, too, assumes that at <strong>Schwetzingen</strong><br />

Pigage had used his architect’s imagination<br />

to create a “historical architecture” in keeping<br />

with Fischer von Erlach’s ideas. 11 It is thus not<br />

surprising that this part of the garden should<br />

have been described as a “Mecca” in Cay<br />

Lorenz Hirschfeld’s Theorie der Gartenkunst<br />

published in 1785: “Consider, for example, the<br />

scene known as Mecca, consisting of a number<br />

of Turkish buildings connected by walks<br />

or arcades. These are so narrow that just two<br />

people can walk side by side.” 12 Apparently<br />

he used what had become the popular name<br />

for that area. There is another indication that<br />

the courtyard was intended as an imitation<br />

of the holy sites of Mecca. The Palatine<br />

court calendar of 1799, explicitly connects<br />

the courtyard of the mosque and the tombs<br />

of prophets: “entourés d’une arcade, aux<br />

environs de laquelle on observe les oratoires<br />

et les logements des prêtres turcs”. 13 Without<br />

being an exact imitation of the Prophet’s tomb<br />

,the courtyard was apparently meant to be<br />

associated with Mecca.<br />

Planning for this area had started in 1773,<br />

long before any mosque building had been<br />

designed; it is unclear whether a mosque was<br />

even planned at that time. Quite possibly the<br />

area was designed independently and with a<br />

signifi cance of its own.<br />

There are more indications that this was the<br />

case. Pigage did not integrate the mosque with<br />

the cloister but instead kept the two separate.<br />

The mosque’s front and main gate face west,<br />

away from the cloister. 14 The building is clearly<br />

not meant to be the focal point and chief<br />

11 Heber 1986, p. 653.<br />

12 Hans Foramitti (ed.), Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld: Theorie<br />

der Gartenkunst, vol. 5, Leipzig 1785, reprint, Hildesheim<br />

1973, p. 344.<br />

13 Quoted after Kurt Martin, Die Kunstdenkmäler des Amtsbezirkes<br />

Mannheim. Stadt <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>, Karlsruhe 1933, p. 298.<br />

14 The reasons were not aesthetic as Martin Gaier believes. Gaier<br />

2002, p. 52.