II. - Schloss Schwetzingen

II. - Schloss Schwetzingen

II. - Schloss Schwetzingen

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

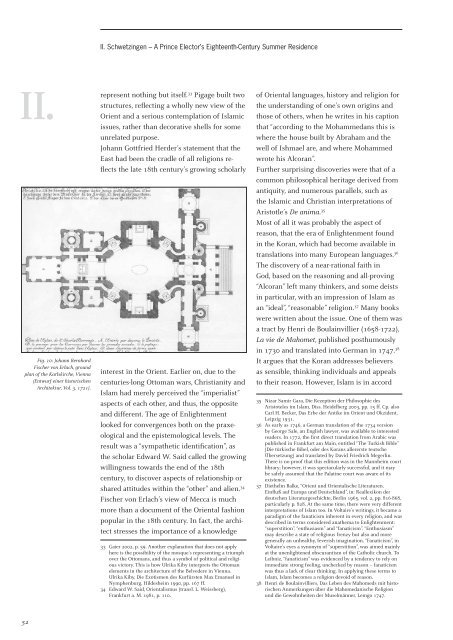

<strong>II</strong>.<br />

Fig. 10: Johann Bernhard<br />

Fischer von Erlach, ground<br />

plan of the Karlskirche, Vienna<br />

(Entwurf einer historischen<br />

Architektur, Vol. 3, 1721).<br />

52<br />

<strong>II</strong>. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – A Prince Elector’s Eighteenth-Century Summer Residence<br />

represent nothing but itself. 33 Pigage built two<br />

structures, refl ecting a wholly new view of the<br />

Orient and a serious contemplation of Islamic<br />

issues, rather than decorative shells for some<br />

unrelated purpose.<br />

Johann Gottfried Herder’s statement that the<br />

East had been the cradle of all religions refl<br />

ects the late 18th century’s growing scholarly<br />

interest in the Orient. Earlier on, due to the<br />

centuries-long Ottoman wars, Christianity and<br />

Islam had merely perceived the “imperialist”<br />

aspects of each other, and thus, the opposite<br />

and different. The age of Enlightenment<br />

looked for convergences both on the praxeological<br />

and the epistemological levels. The<br />

result was a “sympathetic identifi cation”, as<br />

the scholar Edward W. Said called the growing<br />

willingness towards the end of the 18th<br />

century, to discover aspects of relationship or<br />

shared attitudes within the “other” and alien. 34<br />

Fischer von Erlach’s view of Mecca is much<br />

more than a document of the Oriental fashion<br />

popular in the 18th century. In fact, the architect<br />

stresses the importance of a knowledge<br />

33 Gaier 2002, p. 59. Another explanation that does not apply<br />

here is the possibility of the mosque’s representing a triumph<br />

over the Ottomans, and thus a symbol of political and religious<br />

victory. This is how Ulrika Kiby interprets the Ottoman<br />

elements in the architecture of the Belvedere in Vienna.<br />

Ulrika Kiby, Die Exotismen des Kurfürsten Max Emanuel in<br />

Nymphenburg, Hildesheim 1990, pp. 167 ff.<br />

34 Edward W. Said, Orientalismus (transl. L. Weissberg),<br />

Frankfurt a. M. 1981, p. 110.<br />

of Oriental languages, history and religion for<br />

the understanding of one’s own origins and<br />

those of others, when he writes in his caption<br />

that “according to the Mohammedans this is<br />

where the house built by Abraham and the<br />

well of Ishmael are, and where Mohammed<br />

wrote his Alcoran”.<br />

Further surprising discoveries were that of a<br />

common philosophical heritage derived from<br />

antiquity, and numerous parallels, such as<br />

the Islamic and Christian interpretations of<br />

Aristotle’s De anima. 35<br />

Most of all it was probably the aspect of<br />

reason, that the era of Enlightenment found<br />

in the Koran, which had become available in<br />

translations into many European languages. 36<br />

The discovery of a near-rational faith in<br />

God, based on the reasoning and all-proving<br />

“Alcoran” left many thinkers, and some deists<br />

in particular, with an impression of Islam as<br />

an “ideal”, “reasonable” religion. 37 Many books<br />

were written about the issue. One of them was<br />

a tract by Henri de Boulainvillier (1658-1722),<br />

La vie de Mahomet, published posthumously<br />

in 1730 and translated into German in 1747. 38<br />

It argues that the Koran addresses believers<br />

as sensible, thinking individuals and appeals<br />

to their reason. However, Islam is in accord<br />

35 Nizar Samir Gara, Die Rezeption der Philosophie des<br />

Aristoteles im Islam, Diss. Heidelberg 2003, pp. 15 ff. Cp. also<br />

Carl H. Becker, Das Erbe der Antike im Orient und Okzident,<br />

Leipzig 1931.<br />

36 As early as 1746, a German translation of the 1734 version<br />

by George Sale, an English lawyer, was available to interested<br />

readers. In 1772, the fi rst direct translation from Arabic was<br />

published in Frankfurt am Main, entitled “The Turkish Bible”<br />

(Die türkische Bibel, oder des Korans allererste teutsche<br />

Übersetzung) and translated by David Friedrich Megerlin.<br />

There is no proof that this edition was in the Mannheim court<br />

library; however, it was spectacularly successful, and it may<br />

be safely assumed that the Palatine court was aware of its<br />

existence.<br />

37 Diethelm Balke, “Orient und Orientalische Literaturen.<br />

Einfl uß auf Europa und Deutschland”, in: Reallexikon der<br />

deutschen Literaturgeschichte, Berlin 1965, vol. 2, pp. 816-868,<br />

particularly p. 828. At the same time, there were very different<br />

interpretations of Islam too. In Voltaire’s writings, it became a<br />

paradigm of the fanaticism inherent in every religion, and was<br />

described in terms considered anathema to Enlightenment:<br />

“superstition”, “enthusiasm” and “fanaticism”. “Enthusiasm”<br />

may describe a state of religious frenzy but also and more<br />

generally an unhealthy, feverish imagination. “Fanaticism”, in<br />

Voltaire’s eyes a synonym of “superstition”, was aimed mainly<br />

at the unenlightened obscurantism of the Catholic church. To<br />

Leibniz, “fanaticism” was evidenced by a tendency to rely on<br />

immediate strong feeling, unchecked by reason – fanaticism<br />

was thus a lack of clear thinking. In applying these terms to<br />

Islam, Islam becomes a religion devoid of reason.<br />

38 Henri de Boulainvilliers, Das Leben des Mahomeds mit historischen<br />

Anmerkungen über die Mahomedanische Religion<br />

und die Gewohnheiten der Muselmänner, Lemgo 1747.