Combining health and social protection measures to reach the ultra ...

Combining health and social protection measures to reach the ultra ...

Combining health and social protection measures to reach the ultra ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

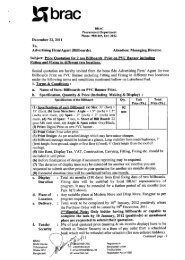

Decision-makingPolicy-makersComplex policy problemsFocused solutionsReducing uncertaintiesSpeedControl <strong>and</strong> delayManipulationFeasible <strong>and</strong> pragmatic solutionsResearchersSimplification of <strong>the</strong> problemInterest in related but separatedissuesFinding <strong>the</strong> truthTime <strong>to</strong> thinkPublish or perilExplanationThoughtful deliberationsSource: Bensing JM. Doing <strong>the</strong> right thing <strong>and</strong> doing it right: <strong>to</strong>ward a framework forassessing <strong>the</strong> policy relevance of <strong>health</strong> service research. International Journal ofTechnology Assessment in Health Care, 2003, 19:604-512.Table 1: Conflicting interests of policy-makers <strong>and</strong> researchersor even fellow researchers in a different field. Researchersoften add a st<strong>and</strong>ard clause at <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong>ir papers statingthat “our research indicates that more research is needed”.This is, of course, both exculpa<strong>to</strong>ry (“don’t blame me if thisisn’t correct”) <strong>and</strong> self-serving (“but if you give me moremoney I might be able <strong>to</strong> give you a better answer”). Hereinlies a key point of distrust: policy-makers believe thatresearchers do research primarily <strong>to</strong> generate more fundingfor more research, <strong>and</strong> not for <strong>the</strong> potential value of <strong>the</strong>research <strong>to</strong> society.“Policy speak” is often used <strong>to</strong> describe <strong>the</strong> language whichpolicy-makers use <strong>and</strong> it often contains acronyms, which inturn are defined by o<strong>the</strong>r acronyms. Much of <strong>the</strong>communication is confidential in nature <strong>and</strong> for a closedaudience, <strong>and</strong> driven by unpublicized political agendas. Theyoften include multiple signatures or are anonymous(containing no signatures), <strong>and</strong> are often stamped as“confidential”. While policy-makers do sometimes conductresearch, it is rare <strong>to</strong> see <strong>the</strong>ir findings published in peerreviewedscientific journals, if released at all. In general, <strong>the</strong>culture of open sharing of knowledge <strong>and</strong> information is notpart of <strong>the</strong> policy-making world.Scientific research in general is driven by fairly long timeframes. Researchers want time for contemplation, thinking,formulating hypo<strong>the</strong>ses, analysis, syn<strong>the</strong>ses, talking <strong>to</strong>colleagues <strong>and</strong> more reflection. In general, it is believed that<strong>the</strong> longer it takes <strong>to</strong> do a research study, <strong>the</strong> better <strong>the</strong>research quality. It is also a fact that <strong>the</strong> process of science isa cumulative one <strong>and</strong> builds on <strong>the</strong> previous work of o<strong>the</strong>rs.Many researchers spend <strong>the</strong>ir entire research career in onenarrow subject area, in order <strong>to</strong> build up <strong>the</strong>ir expertise <strong>and</strong>track record, as well as national <strong>and</strong> international reputationin that area – <strong>to</strong> many, this is an end in itself.In contrast, policy-makers work <strong>to</strong> a very different, muchshorter time scale, often a matter of days or weeks. Answersare always needed instantly <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> time pressures often takeprecedence over quality, since <strong>the</strong>y must have prompt <strong>and</strong>firm opinion <strong>to</strong> look credible. This is reflected in <strong>the</strong> classicpolicy-makers’ sentiment, “I have made up my mind, don’tconfuse me with <strong>the</strong> facts”. Policy-makers usually haveshort tenure managing projects, <strong>and</strong> will move on quickly<strong>to</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r responsibilities, in order <strong>to</strong> build up <strong>the</strong>ir reper<strong>to</strong>ireof expertise in a wide variety of different areas. Theconflicting interests of policy-makers <strong>and</strong> researchers is givenin Table 1.Why are <strong>the</strong>y different?The incompatibilities between researchers <strong>and</strong> policy-makerslead <strong>to</strong> very real problems in terms of promoting better useof evidence for <strong>health</strong> policy development. If <strong>the</strong>y are <strong>to</strong>work <strong>to</strong>ge<strong>the</strong>r, researchers <strong>and</strong> policy-makers must knoweach o<strong>the</strong>r’s strengths <strong>and</strong> weaknesses, as well as likes <strong>and</strong>dislikes. There are a number of key issues that must <strong>the</strong>reforebe addressed.Researchers <strong>and</strong> policy-makers often lack trust <strong>and</strong> respectfor <strong>the</strong> respective roles that <strong>the</strong>y play. Researchers often havea “superiority complex” which translates in<strong>to</strong> acondescending attitude <strong>and</strong> a lack of respect for those whoare not researchers. They often take <strong>the</strong> view that <strong>the</strong>irresearch is <strong>to</strong> be reviewed only by <strong>the</strong>ir peers <strong>and</strong> find itdifficult <strong>to</strong> conduct “directed” or “applied” research,regardless of <strong>the</strong> potential benefits <strong>to</strong> society in general. Theyconsider “academic freedom” <strong>to</strong> be sacrosanct <strong>and</strong> expect <strong>to</strong>be allowed <strong>to</strong> pursue <strong>the</strong>ir interests with no constraints.Therefore, <strong>the</strong>y often resent <strong>the</strong> power of policy-makers <strong>to</strong>control research funding <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> frequent misuse that ismade of scientific data <strong>to</strong> fulfil a politically-driven policyagenda. At <strong>the</strong> same time, policy-makers resent <strong>the</strong> arroganceof researchers, <strong>the</strong> seeming self-fulfilment <strong>and</strong> self-servingnature of much of <strong>the</strong>ir research, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir narrow, tunnelvision approach <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> world. Scientific input is oftenuntimely, less-than-relevant, abstract <strong>and</strong> impossible <strong>to</strong>underst<strong>and</strong> or contextualize. In extreme situations, <strong>the</strong>y viewscientific evidence as being detrimental <strong>to</strong> political <strong>and</strong>economic considerations, e.g. when evidence of an infectiousdisease outbreak can lead <strong>to</strong> economic loss as a result ofreduced numbers of <strong>to</strong>urists.In addition, researchers <strong>and</strong> policy-makers often havedifferent views as <strong>to</strong> what constitutes evidence. Manyscientific results are quantitative <strong>and</strong> can be assessed inrigorous, repeatable ways. Researchers obsess aboutresearch methodology <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> “levels of evidence” ga<strong>the</strong>redthrough different study designs, such as clinical trials <strong>and</strong>observational studies. Policy-makers, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>, areoften more informal in <strong>the</strong>ir assessment of information, eventhat of a quantitative nature. They look for importantinformation based on quick reflections of reality for policymaking,e.g. poll results, opinion surveys, focus groups inmarginal elec<strong>to</strong>rates, anecdotes <strong>and</strong> real-life s<strong>to</strong>ries. Theyoperate on a different hierarchy of evidence – <strong>the</strong>ir “levels ofevidence” may range from “any information that establishes afact or gives reason for believing in something” <strong>to</strong> “availablebody of facts or information indicating a belief or propositionis true or valid”.Should researchers cater <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> needs of policy-makers?Policy-makers are often frustrated because researcherscannot give <strong>the</strong>m a quick, clear <strong>and</strong> simple answer.Researchers are frustrated because required data may notexist, or <strong>the</strong>y do not know <strong>the</strong> answer or want <strong>to</strong> admitproblems with <strong>the</strong>ir studies, or <strong>the</strong>y cannot explain <strong>the</strong>ircomplex findings in a simple language. Policy-makers believethat much of <strong>the</strong> research being conducted is pointless <strong>and</strong>lacks relevance, which is probably right as <strong>the</strong> motivation on<strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> researchers is often scientific curiosity <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>Global Forum Update on Research for Health Volume 4 ✜ 155

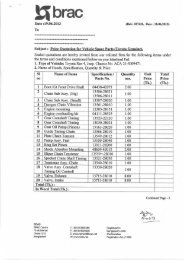

![[re-tender] RFQ for supply of Diesel Generator - Brac](https://img.yumpu.com/44421374/1/186x260/re-tender-rfq-for-supply-of-diesel-generator-brac.jpg?quality=85)