AFRICA AGRICULTURE STATUS REPORT 2016

AASR-report_2016-1

AASR-report_2016-1

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

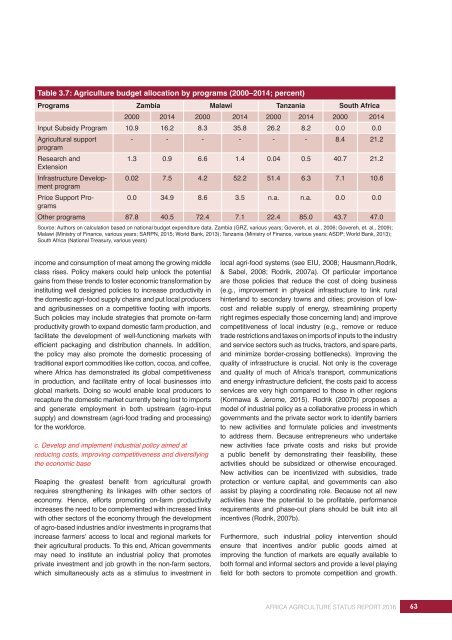

Table 3.7: Agriculture budget allocation by programs (2000–2014; percent)<br />

Programs Zambia Malawi Tanzania South Africa<br />

2000 2014 2000 2014 2000 2014 2000 2014<br />

Input Subsidy Program 10.9 16.2 8.3 35.8 26.2 8.2 0.0 0.0<br />

Agricultural support<br />

- - - - - - 8.4 21.2<br />

program<br />

Research and<br />

1.3 0.9 6.6 1.4 0.04 0.5 40.7 21.2<br />

Extension<br />

Infrastructure Development<br />

0.02 7.5 4.2 52.2 51.4 6.3 7.1 10.6<br />

program<br />

Price Support Programs<br />

0.0 34.9 8.6 3.5 n.a. n.a. 0.0 0.0<br />

Other programs 87.8 40.5 72.4 7.1 22.4 85.0 43.7 47.0<br />

Source: Authors on calculation based on national budget expenditure data. Zambia (GRZ, various years; Govereh, et. al., 2006; Govereh, et. al., 2009);<br />

Malawi (Ministry of Finance, various years; SARPN, 2015; World Bank, 2013); Tanzania (Ministry of Finance, various years; ASDP; World Bank, 2013);<br />

South Africa (National Treasury, various years)<br />

income and consumption of meat among the growing middle<br />

class rises. Policy makers could help unlock the potential<br />

gains from these trends to foster economic transformation by<br />

instituting well designed policies to increase productivity in<br />

the domestic agri-food supply chains and put local producers<br />

and agribusinesses on a competitive footing with imports.<br />

Such policies may include strategies that promote on-farm<br />

productivity growth to expand domestic farm production, and<br />

facilitate the development of well-functioning markets with<br />

efficient packaging and distribution channels. In addition,<br />

the policy may also promote the domestic processing of<br />

traditional export commodities like cotton, cocoa, and coffee,<br />

where Africa has demonstrated its global competitiveness<br />

in production, and facilitate entry of local businesses into<br />

global markets. Doing so would enable local producers to<br />

recapture the domestic market currently being lost to imports<br />

and generate employment in both upstream (agro-input<br />

supply) and downstream (agri-food trading and processing)<br />

for the workforce.<br />

c. Develop and implement industrial policy aimed at<br />

reducing costs, improving competitiveness and diversifying<br />

the economic base<br />

Reaping the greatest benefit from agricultural growth<br />

requires strengthening its linkages with other sectors of<br />

economy. Hence, efforts promoting on-farm productivity<br />

increases the need to be complemented with increased links<br />

with other sectors of the economy through the development<br />

of agro-based industries and/or investments in programs that<br />

increase farmers’ access to local and regional markets for<br />

their agricultural products. To this end, African governments<br />

may need to institute an industrial policy that promotes<br />

private investment and job growth in the non-farm sectors,<br />

which simultaneously acts as a stimulus to investment in<br />

local agri-food systems (see EIU, 2008; Hausmann,Rodrik,<br />

& Sabel, 2008; Rodrik, 2007a). Of particular importance<br />

are those policies that reduce the cost of doing business<br />

(e.g., improvement in physical infrastructure to link rural<br />

hinterland to secondary towns and cities; provision of lowcost<br />

and reliable supply of energy, streamlining property<br />

right regimes especially those concerning land) and improve<br />

competitiveness of local industry (e.g., remove or reduce<br />

trade restrictions and taxes on imports of inputs to the industry<br />

and service sectors such as trucks, tractors, and spare parts,<br />

and minimize border-crossing bottlenecks). Improving the<br />

quality of infrastructure is crucial. Not only is the coverage<br />

and quality of much of Africa’s transport, communications<br />

and energy infrastructure deficient, the costs paid to access<br />

services are very high compared to those in other regions<br />

(Kormawa & Jerome, 2015). Rodrik (2007b) proposes a<br />

model of industrial policy as a collaborative process in which<br />

governments and the private sector work to identify barriers<br />

to new activities and formulate policies and investments<br />

to address them. Because entrepreneurs who undertake<br />

new activities face private costs and risks but provide<br />

a public benefit by demonstrating their feasibility, these<br />

activities should be subsidized or otherwise encouraged.<br />

New activities can be incentivized with subsidies, trade<br />

protection or venture capital, and governments can also<br />

assist by playing a coordinating role. Because not all new<br />

activities have the potential to be profitable, performance<br />

requirements and phase-out plans should be built into all<br />

incentives (Rodrik, 2007b).<br />

Furthermore, such industrial policy intervention should<br />

ensure that incentives and/or public goods aimed at<br />

improving the function of markets are equally available to<br />

both formal and informal sectors and provide a level playing<br />

field for both sectors to promote competition and growth.<br />

<strong>AFRICA</strong> <strong>AGRICULTURE</strong> <strong>STATUS</strong> <strong>REPORT</strong> <strong>2016</strong><br />

63