Why Bad Presentations Happen to Good Causes - The Goodman ...

Why Bad Presentations Happen to Good Causes - The Goodman ...

Why Bad Presentations Happen to Good Causes - The Goodman ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

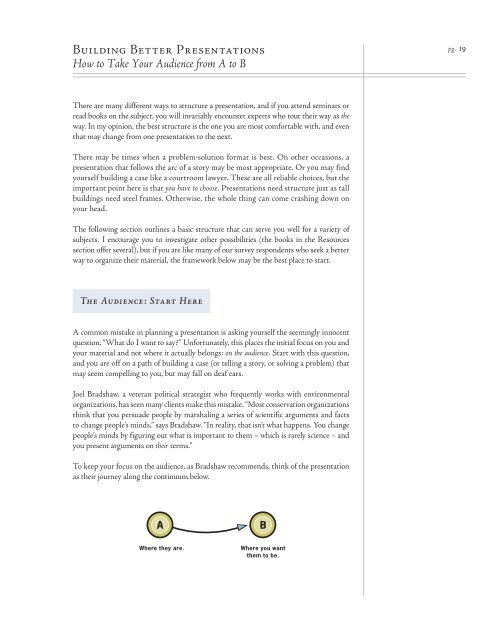

Building Better <strong>Presentations</strong><br />

How <strong>to</strong> Take Your Audience from A <strong>to</strong> B<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are many different ways <strong>to</strong> structure a presentation, and if you attend seminars or<br />

read books on the subject, you will invariably encounter experts who <strong>to</strong>ut their way as the<br />

way. In my opinion, the best structure is the one you are most comfortable with, and even<br />

that may change from one presentation <strong>to</strong> the next.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re may be times when a problem-solution format is best. On other occasions, a<br />

presentation that follows the arc of a s<strong>to</strong>ry may be most appropriate. Or you may find<br />

yourself building a case like a courtroom lawyer. <strong>The</strong>se are all reliable choices, but the<br />

important point here is that you have <strong>to</strong> choose. <strong>Presentations</strong> need structure just as tall<br />

buildings need steel frames. Otherwise, the whole thing can come crashing down on<br />

your head.<br />

<strong>The</strong> following section outlines a basic structure that can serve you well for a variety of<br />

subjects. I encourage you <strong>to</strong> investigate other possibilities (the books in the Resources<br />

section offer several), but if you are like many of our survey respondents who seek a better<br />

way <strong>to</strong> organize their material, the framework below may be the best place <strong>to</strong> start.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Audience: Start Here<br />

A common mistake in planning a presentation is asking yourself the seemingly innocent<br />

question, “What do I want <strong>to</strong> say?” Unfortunately, this places the initial focus on you and<br />

your material and not where it actually belongs: on the audience. Start with this question,<br />

and you are off on a path of building a case (or telling a s<strong>to</strong>ry, or solving a problem) that<br />

may seem compelling <strong>to</strong> you, but may fall on deaf ears.<br />

Joel Bradshaw, a veteran political strategist who frequently works with environmental<br />

organizations, has seen many clients make this mistake. “Most conservation organizations<br />

think that you persuade people by marshaling a series of scientific arguments and facts<br />

<strong>to</strong> change people’s minds,” says Bradshaw. “In reality, that isn’t what happens. You change<br />

people’s minds by figuring out what is important <strong>to</strong> them – which is rarely science – and<br />

you present arguments on their terms.”<br />

To keep your focus on the audience, as Bradshaw recommends, think of the presentation<br />

as their journey along the continuum below.<br />

A<br />

Where they are. Where you want<br />

them <strong>to</strong> be.<br />

B<br />

pg. 19