Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

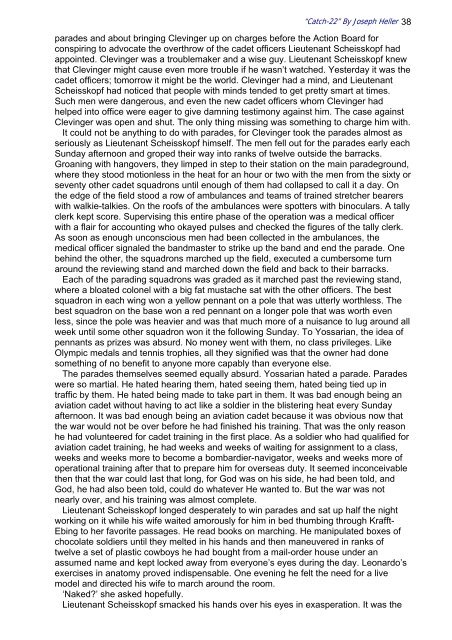

“Catch-22” <strong>By</strong> <strong>Joseph</strong> Heller 38<br />

parades and about bringing Clevinger up on charges before the Action Board for<br />

conspiring to advocate the overthrow of the cadet officers Lieutenant Scheisskopf had<br />

appointed. Clevinger was a troublemaker and a wise guy. Lieutenant Scheisskopf knew<br />

that Clevinger might cause even more trouble if he wasn’t watched. Yesterday it was the<br />

cadet officers; tomorrow it might be the world. Clevinger had a mind, and Lieutenant<br />

Scheisskopf had noticed that people with minds tended to get pretty smart at times.<br />

Such men were dangerous, and even the new cadet officers whom Clevinger had<br />

helped into office were eager to give damning testimony against him. The case against<br />

Clevinger was open and shut. The only thing missing was something to charge him with.<br />

It could not be anything to do with parades, for Clevinger took the parades almost as<br />

seriously as Lieutenant Scheisskopf himself. The men fell out for the parades early each<br />

Sunday afternoon and groped their way into ranks of twelve outside the barracks.<br />

Groaning with hangovers, they limped in step to their station on the main paradeground,<br />

where they stood motionless in the heat for an hour or two with the men from the sixty or<br />

seventy other cadet squadrons until enough of them had collapsed to call it a day. On<br />

the edge of the field stood a row of ambulances and teams of trained stretcher bearers<br />

with walkie-talkies. On the roofs of the ambulances were spotters with binoculars. A tally<br />

clerk kept score. Supervising this entire phase of the operation was a medical officer<br />

with a flair for accounting who okayed pulses and checked the figures of the tally clerk.<br />

As soon as enough unconscious men had been collected in the ambulances, the<br />

medical officer signaled the bandmaster to strike up the band and end the parade. One<br />

behind the other, the squadrons marched up the field, executed a cumbersome turn<br />

around the reviewing stand and marched down the field and back to their barracks.<br />

Each of the parading squadrons was graded as it marched past the reviewing stand,<br />

where a bloated colonel with a big fat mustache sat with the other officers. The best<br />

squadron in each wing won a yellow pennant on a pole that was utterly worthless. The<br />

best squadron on the base won a red pennant on a longer pole that was worth even<br />

less, since the pole was heavier and was that much more of a nuisance to lug around all<br />

week until some other squadron won it the following Sunday. To Yossarian, the idea of<br />

pennants as prizes was absurd. No money went with them, no class privileges. Like<br />

Olympic medals and tennis trophies, all they signified was that the owner had done<br />

something of no benefit to anyone more capably than everyone else.<br />

The parades themselves seemed equally absurd. Yossarian hated a parade. Parades<br />

were so martial. He hated hearing them, hated seeing them, hated being tied up in<br />

traffic by them. He hated being made to take part in them. It was bad enough being an<br />

aviation cadet without having to act like a soldier in the blistering heat every Sunday<br />

afternoon. It was bad enough being an aviation cadet because it was obvious now that<br />

the war would not be over before he had finished his training. That was the only reason<br />

he had volunteered for cadet training in the first place. As a soldier who had qualified for<br />

aviation cadet training, he had weeks and weeks of waiting for assignment to a class,<br />

weeks and weeks more to become a bombardier-navigator, weeks and weeks more of<br />

operational training after that to prepare him for overseas duty. It seemed inconceivable<br />

then that the war could last that long, for God was on his side, he had been told, and<br />

God, he had also been told, could do whatever He wanted to. But the war was not<br />

nearly over, and his training was almost complete.<br />

Lieutenant Scheisskopf longed desperately to win parades and sat up half the night<br />

working on it while his wife waited amorously for him in bed thumbing through Krafft-<br />

Ebing to her favorite passages. He read books on marching. He manipulated boxes of<br />

chocolate soldiers until they melted in his hands and then maneuvered in ranks of<br />

twelve a set of plastic cowboys he had bought from a mail-order house under an<br />

assumed name and kept locked away from everyone’s eyes during the day. Leonardo’s<br />

exercises in anatomy proved indispensable. One evening he felt the need for a live<br />

model and directed his wife to march around the room.<br />

‘Naked?’ she asked hopefully.<br />

Lieutenant Scheisskopf smacked his hands over his eyes in exasperation. It was the