A Greater Australia: Population, policies and governance - CEDA

A Greater Australia: Population, policies and governance - CEDA

A Greater Australia: Population, policies and governance - CEDA

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

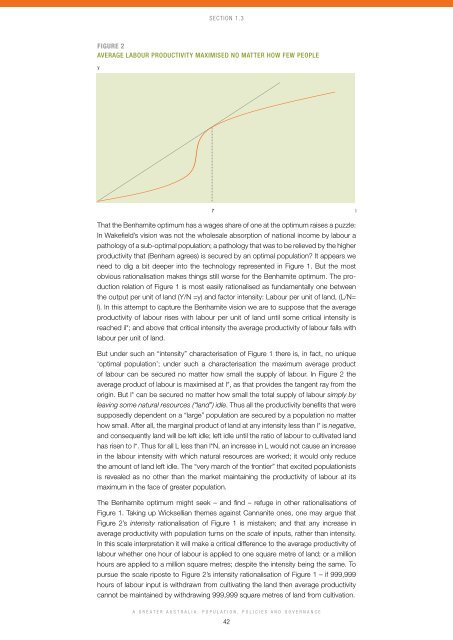

Section 1.3Figure 2Average labour productivity maximised no matter how few peopleyI* IThat the Benhamite optimum has a wages share of one at the optimum raises a puzzle:In Wakefield’s vision was not the wholesale absorption of national income by labour apathology of a sub-optimal population; a pathology that was to be relieved by the higherproductivity that (Benham agrees) is secured by an optimal population? It appears weneed to dig a bit deeper into the technology represented in Figure 1. But the mostobvious rationalisation makes things still worse for the Benhamite optimum. The productionrelation of Figure 1 is most easily rationalised as fundamentally one betweenthe output per unit of l<strong>and</strong> (Y/N =y) <strong>and</strong> factor intensity: Labour per unit of l<strong>and</strong>, (L/N=l). In this attempt to capture the Benhamite vision we are to suppose that the averageproductivity of labour rises with labour per unit of l<strong>and</strong> until some critical intensity isreached il*; <strong>and</strong> above that critical intensity the average productivity of labour falls withlabour per unit of l<strong>and</strong>.But under such an “intensity” characterisation of Figure 1 there is, in fact, no unique‘optimal population’; under such a characterisation the maximum average productof labour can be secured no matter how small the supply of labour. In Figure 2 theaverage product of labour is maximised at l*, as that provides the tangent ray from theorigin. But l* can be secured no matter how small the total supply of labour simply byleaving some natural resources (“l<strong>and</strong>”) idle. Thus all the productivity benefits that weresupposedly dependent on a “large” population are secured by a population no matterhow small. After all, the marginal product of l<strong>and</strong> at any intensity less than l* is negative,<strong>and</strong> consequently l<strong>and</strong> will be left idle; left idle until the ratio of labour to cultivated l<strong>and</strong>has risen to l*. Thus for all L less than l*N, an increase in L would not cause an increasein the labour intensity with which natural resources are worked; it would only reducethe amount of l<strong>and</strong> left idle. The “very march of the frontier” that excited populationistsis revealed as no other than the market maintaining the productivity of labour at itsmaximum in the face of greater population.The Benhamite optimum might seek – <strong>and</strong> find – refuge in other rationalisations ofFigure 1. Taking up Wicksellian themes against Cannanite ones, one may argue thatFigure 2’s intensity rationalisation of Figure 1 is mistaken; <strong>and</strong> that any increase inaverage productivity with population turns on the scale of inputs, rather than intensity.In this scale interpretation it will make a critical difference to the average productivity oflabour whether one hour of labour is applied to one square metre of l<strong>and</strong>; or a millionhours are applied to a million square metres; despite the intensity being the same. Topursue the scale riposte to Figure 2’s intensity rationalisation of Figure 1 – if 999,999hours of labour input is withdrawn from cultivating the l<strong>and</strong> then average productivitycannot be maintained by withdrawing 999,999 square metres of l<strong>and</strong> from cultivation.A <strong>Greater</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>: <strong>Population</strong>, Policies <strong>and</strong> Governance42