Beowulf - Institutionen för arkeologi och antik historia

Beowulf - Institutionen för arkeologi och antik historia

Beowulf - Institutionen för arkeologi och antik historia

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

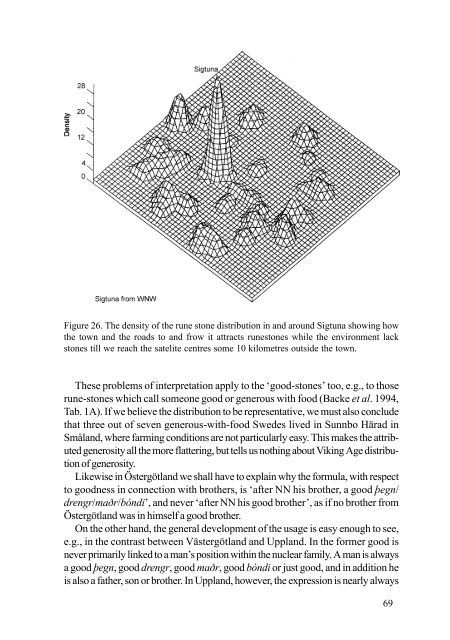

Figure 26. The density of the rune stone distribution in and around Sigtuna showing how<br />

the town and the roads to and frow it attracts runestones while the environment lack<br />

stones till we reach the satelite centres some 10 kilometres outside the town.<br />

These problems of interpretation apply to the ‘good-stones’ too, e.g., to those<br />

rune-stones which call someone good or generous with food (Backe et al. 1994,<br />

Tab. 1A). If we believe the distribution to be representative, we must also conclude<br />

that three out of seven generous-with-food Swedes lived in Sunnbo Härad in<br />

Småland, where farming conditions are not particularly easy. This makes the attributed<br />

generosity all the more flattering, but tells us nothing about Viking Age distribution<br />

of generosity.<br />

Likewise in Östergötland we shall have to explain why the formula, with respect<br />

to goodness in connection with brothers, is ‘after NN his brother, a good þegn/<br />

drengr/maðr/bóndi’, and never ‘after NN his good brother’, as if no brother from<br />

Östergötland was in himself a good brother.<br />

On the other hand, the general development of the usage is easy enough to see,<br />

e.g., in the contrast between Västergötland and Uppland. In the former good is<br />

never primarily linked to a man’s position within the nuclear family. A man is always<br />

a good þegn, good drengr, good maðr, good bóndi or just good, and in addition he<br />

is also a father, son or brother. In Uppland, however, the expression is nearly always<br />

69