The Origin and Evolution of Mammals - Moodle

The Origin and Evolution of Mammals - Moodle

The Origin and Evolution of Mammals - Moodle

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

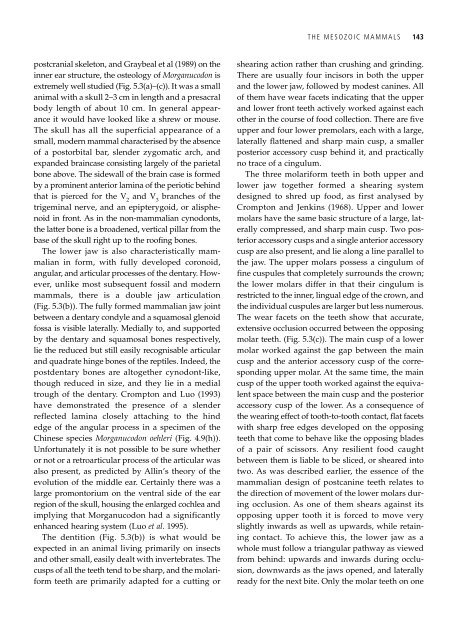

postcranial skeleton, <strong>and</strong> Graybeal et al (1989) on the<br />

inner ear structure, the osteology <strong>of</strong> Morganucodon is<br />

extremely well studied (Fig. 5.3(a)–(c)). It was a small<br />

animal with a skull 2–3 cm in length <strong>and</strong> a presacral<br />

body length <strong>of</strong> about 10 cm. In general appearance<br />

it would have looked like a shrew or mouse.<br />

<strong>The</strong> skull has all the superficial appearance <strong>of</strong> a<br />

small, modern mammal characterised by the absence<br />

<strong>of</strong> a postorbital bar, slender zygomatic arch, <strong>and</strong><br />

exp<strong>and</strong>ed braincase consisting largely <strong>of</strong> the parietal<br />

bone above. <strong>The</strong> sidewall <strong>of</strong> the brain case is formed<br />

by a prominent anterior lamina <strong>of</strong> the periotic behind<br />

that is pierced for the V 2 <strong>and</strong> V 3 branches <strong>of</strong> the<br />

trigeminal nerve, <strong>and</strong> an epipterygoid, or alisphenoid<br />

in front. As in the non-mammalian cynodonts,<br />

the latter bone is a broadened, vertical pillar from the<br />

base <strong>of</strong> the skull right up to the ro<strong>of</strong>ing bones.<br />

<strong>The</strong> lower jaw is also characteristically mammalian<br />

in form, with fully developed coronoid,<br />

angular, <strong>and</strong> articular processes <strong>of</strong> the dentary. However,<br />

unlike most subsequent fossil <strong>and</strong> modern<br />

mammals, there is a double jaw articulation<br />

(Fig. 5.3(b)). <strong>The</strong> fully formed mammalian jaw joint<br />

between a dentary condyle <strong>and</strong> a squamosal glenoid<br />

fossa is visible laterally. Medially to, <strong>and</strong> supported<br />

by the dentary <strong>and</strong> squamosal bones respectively,<br />

lie the reduced but still easily recognisable articular<br />

<strong>and</strong> quadrate hinge bones <strong>of</strong> the reptiles. Indeed, the<br />

postdentary bones are altogether cynodont-like,<br />

though reduced in size, <strong>and</strong> they lie in a medial<br />

trough <strong>of</strong> the dentary. Crompton <strong>and</strong> Luo (1993)<br />

have demonstrated the presence <strong>of</strong> a slender<br />

reflected lamina closely attaching to the hind<br />

edge <strong>of</strong> the angular process in a specimen <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Chinese species Morganucodon oehleri (Fig. 4.9(h)).<br />

Unfortunately it is not possible to be sure whether<br />

or not or a retroarticular process <strong>of</strong> the articular was<br />

also present, as predicted by Allin’s theory <strong>of</strong> the<br />

evolution <strong>of</strong> the middle ear. Certainly there was a<br />

large promontorium on the ventral side <strong>of</strong> the ear<br />

region <strong>of</strong> the skull, housing the enlarged cochlea <strong>and</strong><br />

implying that Morganucodon had a significantly<br />

enhanced hearing system (Luo et al. 1995).<br />

<strong>The</strong> dentition (Fig. 5.3(b)) is what would be<br />

expected in an animal living primarily on insects<br />

<strong>and</strong> other small, easily dealt with invertebrates. <strong>The</strong><br />

cusps <strong>of</strong> all the teeth tend to be sharp, <strong>and</strong> the molariform<br />

teeth are primarily adapted for a cutting or<br />

THE MESOZOIC MAMMALS 143<br />

shearing action rather than crushing <strong>and</strong> grinding.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are usually four incisors in both the upper<br />

<strong>and</strong> the lower jaw, followed by modest canines. All<br />

<strong>of</strong> them have wear facets indicating that the upper<br />

<strong>and</strong> lower front teeth actively worked against each<br />

other in the course <strong>of</strong> food collection. <strong>The</strong>re are five<br />

upper <strong>and</strong> four lower premolars, each with a large,<br />

laterally flattened <strong>and</strong> sharp main cusp, a smaller<br />

posterior accessory cusp behind it, <strong>and</strong> practically<br />

no trace <strong>of</strong> a cingulum.<br />

<strong>The</strong> three molariform teeth in both upper <strong>and</strong><br />

lower jaw together formed a shearing system<br />

designed to shred up food, as first analysed by<br />

Crompton <strong>and</strong> Jenkins (1968). Upper <strong>and</strong> lower<br />

molars have the same basic structure <strong>of</strong> a large, laterally<br />

compressed, <strong>and</strong> sharp main cusp. Two posterior<br />

accessory cusps <strong>and</strong> a single anterior accessory<br />

cusp are also present, <strong>and</strong> lie along a line parallel to<br />

the jaw. <strong>The</strong> upper molars possess a cingulum <strong>of</strong><br />

fine cuspules that completely surrounds the crown;<br />

the lower molars differ in that their cingulum is<br />

restricted to the inner, lingual edge <strong>of</strong> the crown, <strong>and</strong><br />

the individual cuspules are larger but less numerous.<br />

<strong>The</strong> wear facets on the teeth show that accurate,<br />

extensive occlusion occurred between the opposing<br />

molar teeth. (Fig. 5.3(c)). <strong>The</strong> main cusp <strong>of</strong> a lower<br />

molar worked against the gap between the main<br />

cusp <strong>and</strong> the anterior accessory cusp <strong>of</strong> the corresponding<br />

upper molar. At the same time, the main<br />

cusp <strong>of</strong> the upper tooth worked against the equivalent<br />

space between the main cusp <strong>and</strong> the posterior<br />

accessory cusp <strong>of</strong> the lower. As a consequence <strong>of</strong><br />

the wearing effect <strong>of</strong> tooth-to-tooth contact, flat facets<br />

with sharp free edges developed on the opposing<br />

teeth that come to behave like the opposing blades<br />

<strong>of</strong> a pair <strong>of</strong> scissors. Any resilient food caught<br />

between them is liable to be sliced, or sheared into<br />

two. As was described earlier, the essence <strong>of</strong> the<br />

mammalian design <strong>of</strong> postcanine teeth relates to<br />

the direction <strong>of</strong> movement <strong>of</strong> the lower molars during<br />

occlusion. As one <strong>of</strong> them shears against its<br />

opposing upper tooth it is forced to move very<br />

slightly inwards as well as upwards, while retaining<br />

contact. To achieve this, the lower jaw as a<br />

whole must follow a triangular pathway as viewed<br />

from behind: upwards <strong>and</strong> inwards during occlusion,<br />

downwards as the jaws opened, <strong>and</strong> laterally<br />

ready for the next bite. Only the molar teeth on one