ARCHITECTURE

artofinequality_150917_web

artofinequality_150917_web

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

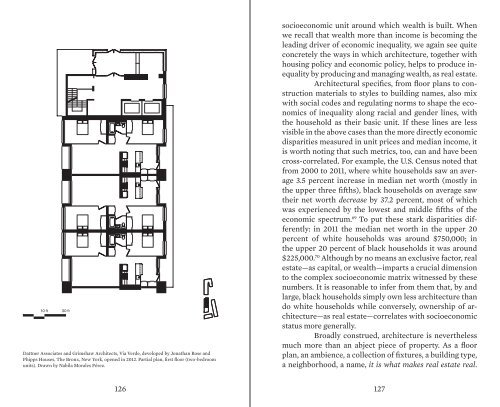

10 ft 20 ft<br />

Dattner Associates and Grimshaw Architects, Via Verde, developed by Jonathan Rose and<br />

Phipps Houses, The Bronx, New York, opened in 2012. Partial plan, first floor (two-bedroom<br />

units). Drawn by Nabila Morales Pérez.<br />

socioeconomic unit around which wealth is built. When<br />

we recall that wealth more than income is becoming the<br />

leading driver of economic inequality, we again see quite<br />

concretely the ways in which architecture, together with<br />

housing policy and economic policy, helps to produce inequality<br />

by producing and managing wealth, as real estate.<br />

Architectural specifics, from floor plans to construction<br />

materials to styles to building names, also mix<br />

with social codes and regulating norms to shape the economics<br />

of inequality along racial and gender lines, with<br />

the household as their basic unit. If these lines are less<br />

visible in the above cases than the more directly economic<br />

disparities measured in unit prices and median income, it<br />

is worth noting that such metrics, too, can and have been<br />

cross-correlated. For example, the U.S. Census noted that<br />

from 2000 to 2011, where white households saw an average<br />

3.5 percent increase in median net worth (mostly in<br />

the upper three fifths), black households on average saw<br />

their net worth decrease by 37.2 percent, most of which<br />

was experienced by the lowest and middle fifths of the<br />

economic spectrum. 69 To put these stark disparities differently:<br />

in 2011 the median net worth in the upper 20<br />

percent of white households was around $750,000; in<br />

the upper 20 percent of black households it was around<br />

$225,000. 70 Although by no means an exclusive factor, real<br />

estate—as capital, or wealth—imparts a crucial dimension<br />

to the complex socioeconomic matrix witnessed by these<br />

numbers. It is reasonable to infer from them that, by and<br />

large, black households simply own less architecture than<br />

do white households while conversely, ownership of architecture—as<br />

real estate—correlates with socioeconomic<br />

status more generally.<br />

Broadly construed, architecture is nevertheless<br />

much more than an abject piece of property. As a floor<br />

plan, an ambience, a collection of fixtures, a building type,<br />

a neighborhood, a name, it is what makes real estate real.<br />

126 127