SHAPING THE FUTURE HOW CHANGING DEMOGRAPHICS CAN POWER HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

1VPo4Vw

1VPo4Vw

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The benefits of<br />

urbanization have not<br />

been equally shared<br />

162<br />

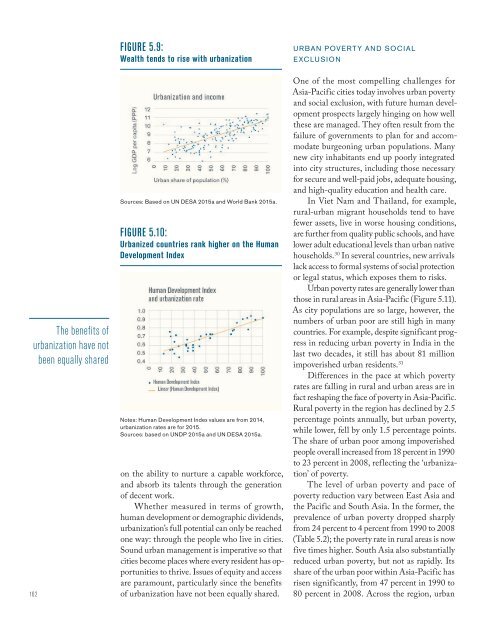

FIGURE 5.9:<br />

Wealth tends to rise with urbanization<br />

Sources: Based on UN DESA 2015a and World Bank 2015a.<br />

FIGURE 5.10:<br />

Urbanized countries rank higher on the Human<br />

Development Index<br />

Notes: Human Development Index values are from 2014,<br />

urbanization rates are for 2015.<br />

Sources: based on UNDP 2015a and UN DESA 2015a.<br />

on the ability to nurture a capable workforce,<br />

and absorb its talents through the generation<br />

of decent work.<br />

Whether measured in terms of growth,<br />

human development or demographic dividends,<br />

urbanization’s full potential can only be reached<br />

one way: through the people who live in cities.<br />

Sound urban management is imperative so that<br />

cities become places where every resident has opportunities<br />

to thrive. Issues of equity and access<br />

are paramount, particularly since the benefits<br />

of urbanization have not been equally shared.<br />

URBAN POVERTY AND SOCIAL<br />

EXCLUSION<br />

One of the most compelling challenges for<br />

Asia-Pacific cities today involves urban poverty<br />

and social exclusion, with future human development<br />

prospects largely hinging on how well<br />

these are managed. They often result from the<br />

failure of governments to plan for and accommodate<br />

burgeoning urban populations. Many<br />

new city inhabitants end up poorly integrated<br />

into city structures, including those necessary<br />

for secure and well-paid jobs, adequate housing,<br />

and high-quality education and health care.<br />

In Viet Nam and Thailand, for example,<br />

rural-urban migrant households tend to have<br />

fewer assets, live in worse housing conditions,<br />

are further from quality public schools, and have<br />

lower adult educational levels than urban native<br />

households. 30 In several countries, new arrivals<br />

lack access to formal systems of social protection<br />

or legal status, which exposes them to risks.<br />

Urban poverty rates are generally lower than<br />

those in rural areas in Asia-Pacific (Figure 5.11).<br />

As city populations are so large, however, the<br />

numbers of urban poor are still high in many<br />

countries. For example, despite significant progress<br />

in reducing urban poverty in India in the<br />

last two decades, it still has about 81 million<br />

impoverished urban residents. 31<br />

Differences in the pace at which poverty<br />

rates are falling in rural and urban areas are in<br />

fact reshaping the face of poverty in Asia-Pacific.<br />

Rural poverty in the region has declined by 2.5<br />

percentage points annually, but urban poverty,<br />

while lower, fell by only 1.5 percentage points.<br />

The share of urban poor among impoverished<br />

people overall increased from 18 percent in 1990<br />

to 23 percent in 2008, reflecting the ‘urbanization’<br />

of poverty.<br />

The level of urban poverty and pace of<br />

poverty reduction vary between East Asia and<br />

the Pacific and South Asia. In the former, the<br />

prevalence of urban poverty dropped sharply<br />

from 24 percent to 4 percent from 1990 to 2008<br />

(Table 5.2); the poverty rate in rural areas is now<br />

five times higher. South Asia also substantially<br />

reduced urban poverty, but not as rapidly. Its<br />

share of the urban poor within Asia-Pacific has<br />

risen significantly, from 47 percent in 1990 to<br />

80 percent in 2008. Across the region, urban