World in Transition: Climate Change as a Security Risk - WBGU

World in Transition: Climate Change as a Security Risk - WBGU

World in Transition: Climate Change as a Security Risk - WBGU

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

108<br />

6 Conflict constellations<br />

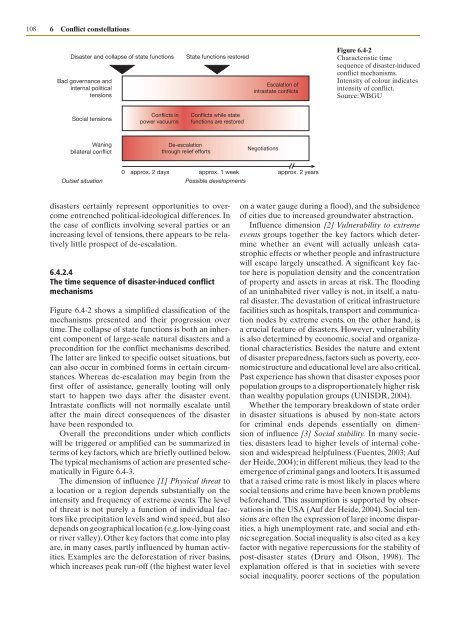

Dis<strong>as</strong>ter and collapse of state functions<br />

Bad governance and<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternal political<br />

tensions<br />

Social tensions<br />

Wan<strong>in</strong>g<br />

bilateral conflict<br />

Outset situation<br />

Conflicts <strong>in</strong><br />

power vacuums<br />

De-escalation<br />

through relief efforts<br />

dis<strong>as</strong>ters certa<strong>in</strong>ly represent opportunities to overcome<br />

entrenched political-ideological differences. In<br />

the c<strong>as</strong>e of conflicts <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g several parties or an<br />

<strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>g level of tensions, there appears to be relatively<br />

little prospect of de-escalation.<br />

6.4.2.4<br />

The time sequence of dis<strong>as</strong>ter-<strong>in</strong>duced conflict<br />

mechanisms<br />

State functions restored<br />

Conflicts while state<br />

functions are restored<br />

0 approx. 2 days approx. 1 week approx. 2 years<br />

Possible developments<br />

Figure 6.4-2 shows a simplified cl<strong>as</strong>sification of the<br />

mechanisms presented and their progression over<br />

time. The collapse of state functions is both an <strong>in</strong>herent<br />

component of large-scale natural dis<strong>as</strong>ters and a<br />

precondition for the conflict mechanisms described.<br />

The latter are l<strong>in</strong>ked to specific outset situations, but<br />

can also occur <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ed forms <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> circumstances.<br />

Where<strong>as</strong> de-escalation may beg<strong>in</strong> from the<br />

first offer of <strong>as</strong>sistance, generally loot<strong>in</strong>g will only<br />

start to happen two days after the dis<strong>as</strong>ter event.<br />

Intra state conflicts will not normally escalate until<br />

after the ma<strong>in</strong> direct consequences of the dis<strong>as</strong>ter<br />

have been responded to.<br />

Overall the preconditions under which conflicts<br />

will be triggered or amplified can be summarized <strong>in</strong><br />

terms of key factors, which are briefly outl<strong>in</strong>ed below.<br />

The typical mechanisms of action are presented schematically<br />

<strong>in</strong> Figure 6.4-3.<br />

The dimension of <strong>in</strong>fluence [1] Physical threat to<br />

a location or a region depends substantially on the<br />

<strong>in</strong>tensity and frequency of extreme events. The level<br />

of threat is not purely a function of <strong>in</strong>dividual factors<br />

like precipitation levels and w<strong>in</strong>d speed, but also<br />

depends on geographical location (e.g. low-ly<strong>in</strong>g co<strong>as</strong>t<br />

or river valley). Other key factors that come <strong>in</strong>to play<br />

are, <strong>in</strong> many c<strong>as</strong>es, partly <strong>in</strong>fluenced by human activities.<br />

Examples are the deforestation of river b<strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>s,<br />

which <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong>es peak run-off (the highest water level<br />

Escalation of<br />

<strong>in</strong>tr<strong>as</strong>tate conflicts<br />

Negotiations<br />

Figure 6.4-2<br />

Characteristic time<br />

sequence of dis<strong>as</strong>ter-<strong>in</strong>duced<br />

conflict mechanisms.<br />

Intensity of colour <strong>in</strong>dicates<br />

<strong>in</strong>tensity of conflict.<br />

Source: <strong>WBGU</strong><br />

on a water gauge dur<strong>in</strong>g a flood), and the subsidence<br />

of cities due to <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong>ed groundwater abstraction.<br />

Influence dimension [2] Vulnerability to extreme<br />

events groups together the key factors which determ<strong>in</strong>e<br />

whether an event will actually unle<strong>as</strong>h cat<strong>as</strong>trophic<br />

effects or whether people and <strong>in</strong>fr<strong>as</strong>tructure<br />

will escape largely unscathed. A significant key factor<br />

here is population density and the concentration<br />

of property and <strong>as</strong>sets <strong>in</strong> are<strong>as</strong> at risk. The flood<strong>in</strong>g<br />

of an un<strong>in</strong>habited river valley is not, <strong>in</strong> itself, a natural<br />

dis<strong>as</strong>ter. The dev<strong>as</strong>tation of critical <strong>in</strong>fr<strong>as</strong>tructure<br />

facilities such <strong>as</strong> hospitals, transport and communication<br />

nodes by extreme events, on the other hand, is<br />

a crucial feature of dis<strong>as</strong>ters. However, vulnerability<br />

is also determ<strong>in</strong>ed by economic, social and organizational<br />

characteristics. Besides the nature and extent<br />

of dis<strong>as</strong>ter preparedness, factors such <strong>as</strong> poverty, economic<br />

structure and educational level are also critical.<br />

P<strong>as</strong>t experience h<strong>as</strong> shown that dis<strong>as</strong>ter exposes poor<br />

population groups to a disproportionately higher risk<br />

than wealthy population groups (UNISDR, 2004).<br />

Whether the temporary breakdown of state order<br />

<strong>in</strong> dis<strong>as</strong>ter situations is abused by non-state actors<br />

for crim<strong>in</strong>al ends depends essentially on dimension<br />

of <strong>in</strong>fluence [3] Social stability. In many societies,<br />

dis<strong>as</strong>ters lead to higher levels of <strong>in</strong>ternal cohesion<br />

and widespread helpfulness (Fuentes, 2003; Auf<br />

der Heide, 2004); <strong>in</strong> different milieus, they lead to the<br />

emergence of crim<strong>in</strong>al gangs and looters. It is <strong>as</strong>sumed<br />

that a raised crime rate is most likely <strong>in</strong> places where<br />

social tensions and crime have been known problems<br />

beforehand. This <strong>as</strong>sumption is supported by observations<br />

<strong>in</strong> the USA (Auf der Heide, 2004). Social tensions<br />

are often the expression of large <strong>in</strong>come disparities,<br />

a high unemployment rate, and social and ethnic<br />

segregation. Social <strong>in</strong>equality is also cited <strong>as</strong> a key<br />

factor with negative repercussions for the stability of<br />

post-dis<strong>as</strong>ter states (Drury and Olson, 1998). The<br />

explanation offered is that <strong>in</strong> societies with severe<br />

social <strong>in</strong>equality, poorer sections of the population