Chronologische - Ethikseite

Chronologische - Ethikseite

Chronologische - Ethikseite

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

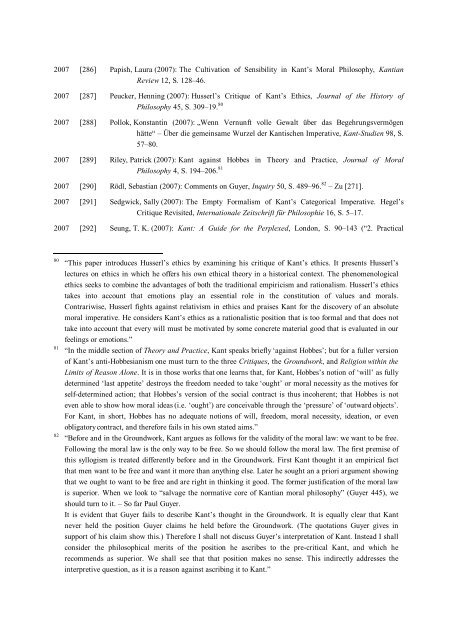

2007 [286] Papish, Laura (2007): The Cultivation of Sensibility in Kant’s Moral Philosophy, Kantian<br />

Review 12, S. 128–46.<br />

2007 [287] Peucker, Henning (2007): Husserl’s Critique of Kant’s Ethics, Journal of the History of<br />

Philosophy 45, S. 309–19. 80<br />

2007 [288] Pollok, Konstantin (2007): „Wenn Vernunft volle Gewalt über das Begehrungsvermögen<br />

hätte“ – Über die gemeinsame Wurzel der Kantischen Imperative, Kant-Studien 98, S.<br />

57–80.<br />

2007 [289] Riley, Patrick (2007): Kant against Hobbes in Theory and Practice, Journal of Moral<br />

Philosophy 4, S. 194–206. 81<br />

2007 [290] Rödl, Sebastian (2007): Comments on Guyer, Inquiry 50, S. 489–96. 82 – Zu [271].<br />

2007 [291] Sedgwick, Sally (2007): The Empty Formalism of Kant’s Categorical Imperative. Hegel’s<br />

Critique Revisited, Internationale Zeitschrift für Philosophie 16, S. 5–17.<br />

2007 [292] Seung, T. K. (2007): Kant: A Guide for the Perplexed, London, S. 90–143 (“2. Practical<br />

80 “This paper introduces Husserl’s ethics by examining his critique of Kant’s ethics. It presents Husserl’s<br />

lectures on ethics in which he offers his own ethical theory in a historical context. The phenomenological<br />

ethics seeks to combine the advantages of both the traditional empiricism and rationalism. Husserl’s ethics<br />

takes into account that emotions play an essential role in the constitution of values and morals.<br />

Contrariwise, Husserl fights against relativism in ethics and praises Kant for the discovery of an absolute<br />

moral imperative. He considers Kant’s ethics as a rationalistic position that is too formal and that does not<br />

take into account that every will must be motivated by some concrete material good that is evaluated in our<br />

feelings or emotions.”<br />

81 “In the middle section of Theory and Practice, Kant speaks briefly ‘against Hobbes’; but for a fuller version<br />

of Kant’s anti-Hobbesianism one must turn to the three Critiques, the Groundwork, and Religion within the<br />

Limits of Reason Alone. It is in those works that one learns that, for Kant, Hobbes’s notion of ‘will’ as fully<br />

determined ‘last appetite’ destroys the freedom needed to take ‘ought’ or moral necessity as the motives for<br />

self-determined action; that Hobbes’s version of the social contract is thus incoherent; that Hobbes is not<br />

even able to show how moral ideas (i.e. ‘ought’) are conceivable through the ‘pressure’ of ‘outward objects’.<br />

For Kant, in short, Hobbes has no adequate notions of will, freedom, moral necessity, ideation, or even<br />

obligatory contract, and therefore fails in his own stated aims.”<br />

82 “Before and in the Groundwork, Kant argues as follows for the validity of the moral law: we want to be free.<br />

Following the moral law is the only way to be free. So we should follow the moral law. The first premise of<br />

this syllogism is treated differently before and in the Groundwork. First Kant thought it an empirical fact<br />

that men want to be free and want it more than anything else. Later he sought an a priori argument showing<br />

that we ought to want to be free and are right in thinking it good. The former justification of the moral law<br />

is superior. When we look to “salvage the normative core of Kantian moral philosophy” (Guyer 445), we<br />

should turn to it. – So far Paul Guyer.<br />

It is evident that Guyer fails to describe Kant’s thought in the Groundwork. It is equally clear that Kant<br />

never held the position Guyer claims he held before the Groundwork. (The quotations Guyer gives in<br />

support of his claim show this.) Therefore I shall not discuss Guyer’s interpretation of Kant. Instead I shall<br />

consider the philosophical merits of the position he ascribes to the pre-critical Kant, and which he<br />

recommends as superior. We shall see that that position makes no sense. This indirectly addresses the<br />

interpretive question, as it is a reason against ascribing it to Kant.”