Chronologische - Ethikseite

Chronologische - Ethikseite

Chronologische - Ethikseite

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

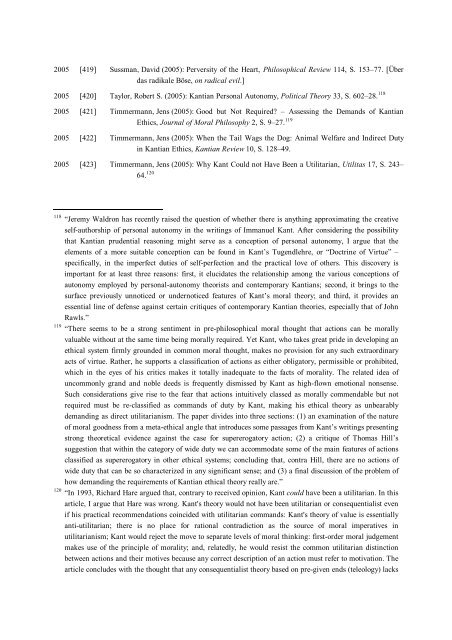

2005 [419] Sussman, David (2005): Perversity of the Heart, Philosophical Review 114, S. 153–77. [Über<br />

das radikale Böse, on radical evil.]<br />

2005 [420] Taylor, Robert S. (2005): Kantian Personal Autonomy, Political Theory 33, S. 602–28. 118<br />

2005 [421] Timmermann, Jens (2005): Good but Not Required? – Assessing the Demands of Kantian<br />

Ethics, Journal of Moral Philosophy 2, S. 9–27. 119<br />

2005 [422] Timmermann, Jens (2005): When the Tail Wags the Dog: Animal Welfare and Indirect Duty<br />

in Kantian Ethics, Kantian Review 10, S. 128–49.<br />

2005 [423] Timmermann, Jens (2005): Why Kant Could not Have Been a Utilitarian, Utilitas 17, S. 243–<br />

64. 120<br />

118 “Jeremy Waldron has recently raised the question of whether there is anything approximating the creative<br />

self-authorship of personal autonomy in the writings of Immanuel Kant. After considering the possibility<br />

that Kantian prudential reasoning might serve as a conception of personal autonomy, I argue that the<br />

elements of a more suitable conception can be found in Kant’s Tugendlehre, or “Doctrine of Virtue” –<br />

specifically, in the imperfect duties of self-perfection and the practical love of others. This discovery is<br />

important for at least three reasons: first, it elucidates the relationship among the various conceptions of<br />

autonomy employed by personal-autonomy theorists and contemporary Kantians; second, it brings to the<br />

surface previously unnoticed or undernoticed features of Kant’s moral theory; and third, it provides an<br />

essential line of defense against certain critiques of contemporary Kantian theories, especially that of John<br />

Rawls.”<br />

119 “There seems to be a strong sentiment in pre-philosophical moral thought that actions can be morally<br />

valuable without at the same time being morally required. Yet Kant, who takes great pride in developing an<br />

ethical system firmly grounded in common moral thought, makes no provision for any such extraordinary<br />

acts of virtue. Rather, he supports a classification of actions as either obligatory, permissible or prohibited,<br />

which in the eyes of his critics makes it totally inadequate to the facts of morality. The related idea of<br />

uncommonly grand and noble deeds is frequently dismissed by Kant as high-flown emotional nonsense.<br />

Such considerations give rise to the fear that actions intuitively classed as morally commendable but not<br />

required must be re-classified as commands of duty by Kant, making his ethical theory as unbearably<br />

demanding as direct utilitarianism. The paper divides into three sections: (1) an examination of the nature<br />

of moral goodness from a meta-ethical angle that introduces some passages from Kant’s writings presenting<br />

strong theoretical evidence against the case for supererogatory action; (2) a critique of Thomas Hill’s<br />

suggestion that within the category of wide duty we can accommodate some of the main features of actions<br />

classified as supererogatory in other ethical systems; concluding that, contra Hill, there are no actions of<br />

wide duty that can be so characterized in any significant sense; and (3) a final discussion of the problem of<br />

how demanding the requirements of Kantian ethical theory really are.”<br />

120 “In 1993, Richard Hare argued that, contrary to received opinion, Kant could have been a utilitarian. In this<br />

article, I argue that Hare was wrong. Kant's theory would not have been utilitarian or consequentialist even<br />

if his practical recommendations coincided with utilitarian commands: Kant's theory of value is essentially<br />

anti-utilitarian; there is no place for rational contradiction as the source of moral imperatives in<br />

utilitarianism; Kant would reject the move to separate levels of moral thinking: first-order moral judgement<br />

makes use of the principle of morality; and, relatedly, he would resist the common utilitarian distinction<br />

between actions and their motives because any correct description of an action must refer to motivation. The<br />

article concludes with the thought that any consequentialist theory based on pre-given ends (teleology) lacks