A history of Greek mathematics Vol.II from Aristarchus to Diophantus by Heath, Thomas Little, Sir, 1921

MACEDONIA is GREECE and will always be GREECE- (if they are desperate to steal a name, Monkeydonkeys suits them just fine) ΚΑΤΩ Η ΣΥΓΚΥΒΕΡΝΗΣΗ ΤΩΝ ΠΡΟΔΟΤΩΝ!!! ΦΕΚ,ΚΚΕ,ΚΝΕ,ΚΟΜΜΟΥΝΙΣΜΟΣ,ΣΥΡΙΖΑ,ΠΑΣΟΚ,ΝΕΑ ΔΗΜΟΚΡΑΤΙΑ,ΕΓΚΛΗΜΑΤΑ,ΔΑΠ-ΝΔΦΚ, MACEDONIA,ΣΥΜΜΟΡΙΤΟΠΟΛΕΜΟΣ,ΠΡΟΣΦΟΡΕΣ,ΥΠΟΥΡΓΕΙΟ,ΕΝΟΠΛΕΣ ΔΥΝΑΜΕΙΣ,ΣΤΡΑΤΟΣ, ΑΕΡΟΠΟΡΙΑ,ΑΣΤΥΝΟΜΙΑ,ΔΗΜΑΡΧΕΙΟ,ΝΟΜΑΡΧΙΑ,ΠΑΝΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΙΟ,ΛΟΓΟΤΕΧΝΙΑ,ΔΗΜΟΣ,LIFO,ΛΑΡΙΣΑ, ΠΕΡΙΦΕΡΕΙΑ,ΕΚΚΛΗΣΙΑ,ΟΝΝΕΔ,ΜΟΝΗ,ΠΑΤΡΙΑΡΧΕΙΟ,ΜΕΣΗ ΕΚΠΑΙΔΕΥΣΗ,ΙΑΤΡΙΚΗ,ΟΛΜΕ,ΑΕΚ,ΠΑΟΚ,ΦΙΛΟΛΟΓΙΚΑ,ΝΟΜΟΘΕΣΙΑ,ΔΙΚΗΓΟΡΙΚΟΣ,ΕΠΙΠΛΟ, ΣΥΜΒΟΛΑΙΟΓΡΑΦΙΚΟΣ,ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΑ,ΜΑΘΗΜΑΤΙΚΑ,ΝΕΟΛΑΙΑ,ΟΙΚΟΝΟΜΙΚΑ,ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ,ΙΣΤΟΡΙΚΑ,ΑΥΓΗ,ΤΑ ΝΕΑ,ΕΘΝΟΣ,ΣΟΣΙΑΛΙΣΜΟΣ,LEFT,ΕΦΗΜΕΡΙΔΑ,ΚΟΚΚΙΝΟ,ATHENS VOICE,ΧΡΗΜΑ,ΟΙΚΟΝΟΜΙΑ,ΕΝΕΡΓΕΙΑ, ΡΑΤΣΙΣΜΟΣ,ΠΡΟΣΦΥΓΕΣ,GREECE,ΚΟΣΜΟΣ,ΜΑΓΕΙΡΙΚΗ,ΣΥΝΤΑΓΕΣ,ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΣ,ΕΛΛΑΔΑ, ΕΜΦΥΛΙΟΣ,ΤΗΛΕΟΡΑΣΗ,ΕΓΚΥΚΛΙΟΣ,ΡΑΔΙΟΦΩΝΟ,ΓΥΜΝΑΣΤΙΚΗ,ΑΓΡΟΤΙΚΗ,ΟΛΥΜΠΙΑΚΟΣ, ΜΥΤΙΛΗΝΗ,ΧΙΟΣ,ΣΑΜΟΣ,ΠΑΤΡΙΔΑ,ΒΙΒΛΙΟ,ΕΡΕΥΝΑ,ΠΟΛΙΤΙΚΗ,ΚΥΝΗΓΕΤΙΚΑ,ΚΥΝΗΓΙ,ΘΡΙΛΕΡ, ΠΕΡΙΟΔΙΚΟ,ΤΕΥΧΟΣ,ΜΥΘΙΣΤΟΡΗΜΑ,ΑΔΩΝΙΣ ΓΕΩΡΓΙΑΔΗΣ,GEORGIADIS,ΦΑΝΤΑΣΤΙΚΕΣ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΕΣ, ΑΣΤΥΝΟΜΙΚΑ,ΦΙΛΟΣΟΦΙΚΗ,ΦΙΛΟΣΟΦΙΚΑ,ΙΚΕΑ,ΜΑΚΕΔΟΝΙΑ,ΑΤΤΙΚΗ,ΘΡΑΚΗ,ΘΕΣΣΑΛΟΝΙΚΗ,ΠΑΤΡΑ, ΙΟΝΙΟ,ΚΕΡΚΥΡΑ,ΚΩΣ,ΡΟΔΟΣ,ΚΑΒΑΛΑ,ΜΟΔΑ,ΔΡΑΜΑ,ΣΕΡΡΕΣ,ΕΥΡΥΤΑΝΙΑ,ΠΑΡΓΑ,ΚΕΦΑΛΟΝΙΑ, ΙΩΑΝΝΙΝΑ,ΛΕΥΚΑΔΑ,ΣΠΑΡΤΗ,ΠΑΞΟΙ

MACEDONIA is GREECE and will always be GREECE- (if they are desperate to steal a name, Monkeydonkeys suits them just fine)

ΚΑΤΩ Η ΣΥΓΚΥΒΕΡΝΗΣΗ ΤΩΝ ΠΡΟΔΟΤΩΝ!!!

ΦΕΚ,ΚΚΕ,ΚΝΕ,ΚΟΜΜΟΥΝΙΣΜΟΣ,ΣΥΡΙΖΑ,ΠΑΣΟΚ,ΝΕΑ ΔΗΜΟΚΡΑΤΙΑ,ΕΓΚΛΗΜΑΤΑ,ΔΑΠ-ΝΔΦΚ, MACEDONIA,ΣΥΜΜΟΡΙΤΟΠΟΛΕΜΟΣ,ΠΡΟΣΦΟΡΕΣ,ΥΠΟΥΡΓΕΙΟ,ΕΝΟΠΛΕΣ ΔΥΝΑΜΕΙΣ,ΣΤΡΑΤΟΣ, ΑΕΡΟΠΟΡΙΑ,ΑΣΤΥΝΟΜΙΑ,ΔΗΜΑΡΧΕΙΟ,ΝΟΜΑΡΧΙΑ,ΠΑΝΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΙΟ,ΛΟΓΟΤΕΧΝΙΑ,ΔΗΜΟΣ,LIFO,ΛΑΡΙΣΑ, ΠΕΡΙΦΕΡΕΙΑ,ΕΚΚΛΗΣΙΑ,ΟΝΝΕΔ,ΜΟΝΗ,ΠΑΤΡΙΑΡΧΕΙΟ,ΜΕΣΗ ΕΚΠΑΙΔΕΥΣΗ,ΙΑΤΡΙΚΗ,ΟΛΜΕ,ΑΕΚ,ΠΑΟΚ,ΦΙΛΟΛΟΓΙΚΑ,ΝΟΜΟΘΕΣΙΑ,ΔΙΚΗΓΟΡΙΚΟΣ,ΕΠΙΠΛΟ, ΣΥΜΒΟΛΑΙΟΓΡΑΦΙΚΟΣ,ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΑ,ΜΑΘΗΜΑΤΙΚΑ,ΝΕΟΛΑΙΑ,ΟΙΚΟΝΟΜΙΚΑ,ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ,ΙΣΤΟΡΙΚΑ,ΑΥΓΗ,ΤΑ ΝΕΑ,ΕΘΝΟΣ,ΣΟΣΙΑΛΙΣΜΟΣ,LEFT,ΕΦΗΜΕΡΙΔΑ,ΚΟΚΚΙΝΟ,ATHENS VOICE,ΧΡΗΜΑ,ΟΙΚΟΝΟΜΙΑ,ΕΝΕΡΓΕΙΑ, ΡΑΤΣΙΣΜΟΣ,ΠΡΟΣΦΥΓΕΣ,GREECE,ΚΟΣΜΟΣ,ΜΑΓΕΙΡΙΚΗ,ΣΥΝΤΑΓΕΣ,ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΣ,ΕΛΛΑΔΑ, ΕΜΦΥΛΙΟΣ,ΤΗΛΕΟΡΑΣΗ,ΕΓΚΥΚΛΙΟΣ,ΡΑΔΙΟΦΩΝΟ,ΓΥΜΝΑΣΤΙΚΗ,ΑΓΡΟΤΙΚΗ,ΟΛΥΜΠΙΑΚΟΣ, ΜΥΤΙΛΗΝΗ,ΧΙΟΣ,ΣΑΜΟΣ,ΠΑΤΡΙΔΑ,ΒΙΒΛΙΟ,ΕΡΕΥΝΑ,ΠΟΛΙΤΙΚΗ,ΚΥΝΗΓΕΤΙΚΑ,ΚΥΝΗΓΙ,ΘΡΙΛΕΡ, ΠΕΡΙΟΔΙΚΟ,ΤΕΥΧΟΣ,ΜΥΘΙΣΤΟΡΗΜΑ,ΑΔΩΝΙΣ ΓΕΩΡΓΙΑΔΗΣ,GEORGIADIS,ΦΑΝΤΑΣΤΙΚΕΣ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΕΣ, ΑΣΤΥΝΟΜΙΚΑ,ΦΙΛΟΣΟΦΙΚΗ,ΦΙΛΟΣΟΦΙΚΑ,ΙΚΕΑ,ΜΑΚΕΔΟΝΙΑ,ΑΤΤΙΚΗ,ΘΡΑΚΗ,ΘΕΣΣΑΛΟΝΙΚΗ,ΠΑΤΡΑ, ΙΟΝΙΟ,ΚΕΡΚΥΡΑ,ΚΩΣ,ΡΟΔΟΣ,ΚΑΒΑΛΑ,ΜΟΔΑ,ΔΡΑΜΑ,ΣΕΡΡΕΣ,ΕΥΡΥΤΑΝΙΑ,ΠΑΡΓΑ,ΚΕΦΑΛΟΝΙΑ, ΙΩΑΝΝΙΝΑ,ΛΕΥΚΑΔΑ,ΣΠΑΡΤΗ,ΠΑΞΟΙ

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

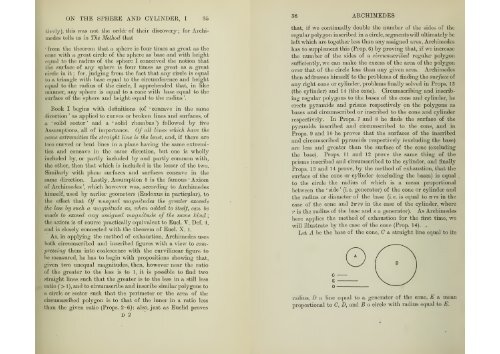

ON THE SPHERE AND CYLINDER, I 35<br />

tively), this was not the order <strong>of</strong> their discovery ; for Archimedes<br />

tells us in The Method that<br />

'<br />

<strong>from</strong> the theorem that a sphere is four times as great as the<br />

cone with a great circle <strong>of</strong> the sphere as base and with height<br />

equal <strong>to</strong> the radius <strong>of</strong> the sphere I conceived the notion that<br />

the surface <strong>of</strong> any sphere is four times as great as a great<br />

circle in it ; for, judging <strong>from</strong> the fact that any circle is equal<br />

<strong>to</strong> a triangle with base equal <strong>to</strong> the circumference and height<br />

equal <strong>to</strong> the radius <strong>of</strong> the circle, I apprehended that, in like<br />

manner, any sphere is equal <strong>to</strong> a cone with base equal <strong>to</strong> the<br />

surface <strong>of</strong> the sphere and height equal <strong>to</strong> the radius '.<br />

Book I begins with definitions (<strong>of</strong> ' concave in the same<br />

direction as applied '<br />

<strong>to</strong> curves or broken lines and surfaces, <strong>of</strong><br />

a ' solid sec<strong>to</strong>r ' and a ' solid rhombus ') followed <strong>by</strong> five<br />

Assumptions, all <strong>of</strong> importance. Of all lines ivhich have the<br />

same extremities the straight line is the least, and, if there are<br />

two curved or bent lines in a plane having the same extremities<br />

and concave in the same direction, but one is wholly<br />

included <strong>by</strong>, or partly included <strong>by</strong> and partly common with,<br />

the other, then that which is included is the lesser <strong>of</strong> the two.<br />

Similarly with plane surfaces and surfaces concave in the<br />

'<br />

same direction. Lastly, Assumption 5 is the famous Axiom<br />

<strong>of</strong> Archimedes ', which however was, according <strong>to</strong> Archimedes<br />

himself, used <strong>by</strong> earlier geometers (Eudoxus in particular), <strong>to</strong><br />

the effect that Of unequal magnitudes the greater exceeds<br />

the less <strong>by</strong> such a magnitude as, when added <strong>to</strong> itself, can be<br />

made <strong>to</strong> exceed any assigned magnitude <strong>of</strong> the same kind<br />

;<br />

the axiom is <strong>of</strong> course practically equivalent <strong>to</strong> Eucl. V, Def. 4,<br />

and is closely connected with the theorem <strong>of</strong> Eucl. X. 1.<br />

As, in applying the method <strong>of</strong> exhaustion, Archimedes uses<br />

both circumscribed and inscribed figures with a view <strong>to</strong> compressing<br />

them in<strong>to</strong> coalescence with the curvilinear figure <strong>to</strong><br />

be measured, he has <strong>to</strong> begin with propositions showing that,<br />

given two unequal magnitudes, then, however near the ratio<br />

<strong>of</strong> the greater <strong>to</strong> the less is <strong>to</strong> 1, it is possible <strong>to</strong> find two<br />

straight lines such that the greater is <strong>to</strong> the less in a still less<br />

ratio ( > 1), and <strong>to</strong> circumscribe and inscribe similar polygons <strong>to</strong><br />

a circle or sec<strong>to</strong>r such that the perimeter or the area <strong>of</strong> the<br />

circumscribed polygon is <strong>to</strong> that <strong>of</strong> the inner in a ratio less<br />

than the given ratio (Props. 2-6): also, just as Euclid proves<br />

D 2<br />

36 ARCHIMEDES<br />

that, if we continually double the number <strong>of</strong> the sides <strong>of</strong> the<br />

regular polygon inscribed in a circle, segments will ultimately be<br />

left which are <strong>to</strong>gether less than any assigned area, Archimedes<br />

has <strong>to</strong> supplement this (Prop. 6) <strong>by</strong> proving that, if we increase<br />

the number <strong>of</strong> the sides <strong>of</strong> a circumscribed regular polygon<br />

sufficiently, we can make the excess <strong>of</strong> the area <strong>of</strong> the polygon<br />

over that <strong>of</strong> the circle less than any given area. Archimedes<br />

then addresses himself <strong>to</strong> the problems <strong>of</strong> finding the surface <strong>of</strong><br />

any right cone or cylinder, problems finally solved in Props. 1<br />

(the cylinder) and 14 (the cone).<br />

Circumscribing and inscribing<br />

regular polygons <strong>to</strong> the bases <strong>of</strong> the cone and cylinder, he<br />

erects pyramids and prisms respectively on the polygons as<br />

bases and circumscribed or inscribed <strong>to</strong> the cone and cylinder<br />

respectively. In Props. 7 and 8 he finds the surface <strong>of</strong> the<br />

pyramids inscribed and circumscribed <strong>to</strong> the cone, and in<br />

Props. 9 and 10 he proves that the surfaces <strong>of</strong> the inscribed<br />

and circumscribed pyramids respectively (excluding the base)<br />

are less and greater than the surface <strong>of</strong> the cone (excluding<br />

the base). Props. 11 and 12 prove the same thing <strong>of</strong> the<br />

prisms inscribed and circumscribed <strong>to</strong> the cylinder, and finally<br />

Props. 13 and 14 prove, <strong>by</strong> the method <strong>of</strong> exhaustion, that the<br />

surface <strong>of</strong> the cone or cylinder (excluding the bases) is equal<br />

<strong>to</strong> the circle the radius <strong>of</strong> which is a mean proportional<br />

between the ' side ' (i. e. genera<strong>to</strong>r) <strong>of</strong> the cone or cylinder and<br />

the radius or diameter <strong>of</strong> the base (i.e. is equal <strong>to</strong> wrs in the<br />

case <strong>of</strong> the cone and 2irrs in the case <strong>of</strong> the cylinder, where<br />

r is the radius <strong>of</strong> the base and s a genera<strong>to</strong>r). As Archimedes<br />

here applies the method <strong>of</strong> exhaustion for the first time, we<br />

will illustrate <strong>by</strong> the case <strong>of</strong> the cone (Prop. 14). .<br />

Let A be the base <strong>of</strong><br />

c<br />

E<br />

the cone, C a straight line equal <strong>to</strong> its<br />

radius, D a line equal <strong>to</strong> a genera<strong>to</strong>r <strong>of</strong> the cone, E a mean<br />

proportional <strong>to</strong> G, D, and B a circle with radius equal <strong>to</strong> E.