- Page 1 and 2:

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY OF IND

- Page 3 and 4:

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION THIS b

- Page 5 and 6:

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION xiii a

- Page 7 and 8:

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION xv Rgv

- Page 9 and 10:

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY AB A

- Page 11 and 12:

xxi ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Page 13 and 14:

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY I-ts

- Page 15 and 16:

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY t xx

- Page 17 and 18:

CHRONOLOGICAL OUTLINE No chronology

- Page 19 and 20:

XXIX CHRONOLOGICAL OUTLINE crowns a

- Page 21 and 22:

Ixiv COMMENTARY TO ILLUSTRATIONS 6.

- Page 23 and 24:

COMMENTARY TO ILLUSTRATIONS number

- Page 25 and 26:

Ixviii COMMENTARY TO ILLUSTRATIONS

- Page 27 and 28:

CHAPTER I SCOPE AND METHODS 1.1. Sp

- Page 29 and 30:

1.1J GANGEYADEVA ‘AND BENGAL 3 (w

- Page 31 and 32:

1.1] LEGENDS NOT HISTORY 5 still cu

- Page 33 and 34:

1.2] ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOGRAPHY 7

- Page 35 and 36:

1.3J THE MATERIALIST APPROACH 9 kno

- Page 37 and 38:

1.3] VILLAGE PRODUCTION 11 “These

- Page 39 and 40:

1.3] FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS 13 were

- Page 41 and 42:

NOTES TO CHAPTER I 15 3. F. E. Parg

- Page 43 and 44:

CHAPTER II THE HERITAGE OF PRE- CLA

- Page 45 and 46:

2.1] EARLY TOOLS AND MATERIALS 19 T

- Page 47 and 48:

2.2] TRIBAL STRUCTURE 21 built, lik

- Page 49 and 50:

2.2] RITUAL AND SACRIFICE 23 But sl

- Page 51 and 52:

2.2] POWER OF GROUP LIFE 25 The bas

- Page 53 and 54:

2.3] CASTES FROM TRIBES 27 tribal p

- Page 55 and 56:

2.3] PARDHI CUSTOMS 29 clans are no

- Page 57 and 58:

2.3] VAIDUS AND VADDARS 31 The buri

- Page 59 and 60:

2.3] THE PROCESS OF ABSORPTION 33 I

- Page 61 and 62:

2.4] VETALA AND HANUMAN 35 converte

- Page 63 and 64:

2.4] 37 STONE MICROLITHS which has

- Page 65 and 66:

2.4] THE PASTORAL GODS 39 that beyo

- Page 67 and 68:

2.5] TREE CULTS 41 (a demon), Kalub

- Page 69 and 70:

2.5] SYNCRETISM IN CULTS 43 is marr

- Page 71 and 72:

2.5] ANCIENT SURVIVALS 45 has been

- Page 73 and 74:

SURVIVAL OF PRIMITIVE IMPLEMENTS 47

- Page 75 and 76:

2.6J ARCHAIC POTTERY TECHNIQUE 49 m

- Page 77 and 78:

NOTES TO CHAPTER II 51 castes many

- Page 79 and 80:

CHAPTER III CIVILIZATION AND BARBAR

- Page 81 and 82:

3.1] INCORRECT AND CORRECT DEDUCTIO

- Page 83 and 84:

3.2] IMPORTANCE OF RIPARIAN DESERTS

- Page 85 and 86:

3,2] TRADE WITH BABYLON 59 similari

- Page 87 and 88:

3.2] NAVIGATION, INTERNAL TRADE 61

- Page 89 and 90:

3.3] FORCE OR RELIGION? 63 containi

- Page 91 and 92:

3.3] DOMINANCE OF RELIGION 65 a cul

- Page 93 and 94:

3.4] PROBLEM OF FOOT PRODUCTION 67

- Page 95 and 96:

3.4] METHODS OF CULTIVATION 69 Indi

- Page 97 and 98:

3.4] FLOOD IRRIGATION 71 but does n

- Page 99 and 100:

3.4) HARAPPA IN THE RGVEDA 73 Harap

- Page 101 and 102:

3.4] DESTRUCTION OF THE DAMS 75 Thi

- Page 103 and 104:

NOTES TO CHAPTER III 77 R. E. M. Wh

- Page 105 and 106:

NOTES TO CHAPTER III 79 The very ac

- Page 107 and 108:

4.1J ARYANS IN HISTORY 81 Aryans in

- Page 109 and 110:

4. 1J TWO ARYAN WAVES 83 The commun

- Page 111 and 112:

4.1J DEMOLITION OF BARRIERS 85 diff

- Page 113 and 114:

4.2] OLD ARYAN GODS 87 The novice w

- Page 115 and 116:

4.2] CONTINUED FOREIGN CONTACTS 89

- Page 117 and 118:

4.3] MYTH AND HISTORY 91 The second

- Page 119 and 120:

4.3] HUMAN AND DEMONIC DASAS 93 ult

- Page 121 and 122:

4.3J PURUS, BHRGUS, TRTSUS 95 in RV

- Page 123 and 124:

4.4] THE FORMATION OF THE FIRST CAS

- Page 125 and 126:

4.4] FOUR CLASS-CASTES 99 intermarr

- Page 127 and 128:

4.5] ORIGINS OF BRAHMINISM 101 It h

- Page 129 and 130:

4.5] NEED FOR AN URBAN BACKGROUND 1

- Page 131 and 132:

4.5] BRAHMIN GOTRAS FROM TRIBES 105

- Page 133 and 134:

NOTES TO CHAPTER IV 107 Kasi-Kosala

- Page 135 and 136:

NOTES TO CHAPTER IV 109 12. In addi

- Page 137 and 138:

5.1] MODE OF LIVING 111 only in the

- Page 139 and 140:

5. 1J ANTHROPOMETRY of such measure

- Page 141 and 142:

5.2] EFFECT OF THE PLOUGH 115 into

- Page 143 and 144:

5.2] NEED FOR CRITICAL EDITIONS 117

- Page 145 and 146:

5.3] RISE OF NEW TRIBES 119 in the

- Page 147 and 148:

5.3] CATTLE, CROPS, TRADE 121 be an

- Page 149 and 150:

5.4] ARYAN LAND-CLEARING 123 design

- Page 151 and 152:

5.5] UTOPIAN KURUS ; IKSVAKUS 125 w

- Page 153 and 154:

5.5] BHRGU MYTHS 127 Just why he ha

- Page 155 and 156:

5.6] DIFFUSION OF NAGA CULTURE 129

- Page 157 and 158:

5.6] TOTEMIC SURVIVALS 131 Totemism

- Page 159 and 160:

5.7J POOR PRIEST-CLASS 133 Both got

- Page 161 and 162:

5.8J MIXED BRAHMINS 135 6.4.16 for

- Page 163 and 164:

5.8] SESAMUM OIL 137 The word taila

- Page 165 and 166:

5.8J NEW FORMS OF PROPERTY 139 now

- Page 167 and 168:

5.9] CHANGES IN SOCIAL STRUCTURE 14

- Page 169 and 170:

NOTES TO CHAPTER V 143 Satyakama Ja

- Page 171 and 172:

6.1] THE PUNJAB 145 destruction of

- Page 173 and 174:

6.1J DEBT AND USURY 147 down to Kau

- Page 175 and 176:

6.2] CONTEMPORARY GANGETIC TRIBES 1

- Page 177 and 178:

6.2] TRIBAL JANAPADAS 151 Pavarika,

- Page 179 and 180:

6.3J BASIS OF ABSOLUTE MONARCHT 153

- Page 181 and 182:

6.3J MAGADHAN CONTROL OF METALS 155

- Page 183 and 184:

157 Fig. 20. Later Kosalan coinage

- Page 185 and 186:

6.$J THE FALL OF KOSALA 159 brahmin

- Page 187 and 188:

6.4J DESTRUCTION OF THE LICCHAVIS 1

- Page 189 and 190:

6.5] CONTEMPORARY MAGADHAN SECTS 16

- Page 191 and 192:

6.6J; NEW DOCTRINES 165 committed i

- Page 193 and 194:

6.6} PROPERTY AND RELIGION 167 upon

- Page 195 and 196: 6.6] CASTE 169 bearing the message

- Page 197 and 198: 6.7J THE GREAT NEGATION ; TAXILA 17

- Page 199 and 200: 6.7J APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES 173

- Page 201 and 202: 6.7J SYSTEM OF PUNCH-MARKS 175 Thou

- Page 203 and 204: NANDAS 177 the humped bull ) may be

- Page 205 and 206: ROYAL MARKS ON COINS 179 Fig. 26. W

- Page 207 and 208: 6.7J RUIN OF TAXILA 181 They also s

- Page 209 and 210: 6.7] INFORMATION FROM HOARDS 183 So

- Page 211 and 212: CHAPTER VII THE FORMATION OF A VILL

- Page 213 and 214: MAURYAN CONQUESTS 187 manifestation

- Page 215 and 216: 7.2] ALEXANDER AT TAXILA 189 Fig. 3

- Page 217 and 218: 7.2] INDIAN MILITARY TACTICS 191 Th

- Page 219 and 220: 7.2ij MEGASTHENES ON MAGADHAN SOCIE

- Page 221 and 222: AUTONOMOUS JANAPADAS 195 anywhere i

- Page 223 and 224: 7.3J ASOKAN MONUMENTS 197 ; only a

- Page 225 and 226: 7.3J KINSHIP ; TRACK ROUTES 199 kin

- Page 227 and 228: ECONOMIC STRAIN 201 be it would hav

- Page 229 and 230: 7.3] ATTACHMENT TO BUDDHISM 203 bes

- Page 231 and 232: 7.3] INFLUENCE UPON RELIGION 205 Th

- Page 233 and 234: 7.3J NEW IDEAL OF KINGSHIP 207 admi

- Page 235 and 236: 7:4] THE LANGUAGE OF ASOKAN EDICTS

- Page 237 and 238: 7.4] SUPPORT FOR EARLIER DATE 211 T

- Page 239 and 240: 7.4] TECHNIQUE OF DISRUPTING TRIBES

- Page 241 and 242: 7.4] ARTHASASTRA REALISM 215 occupa

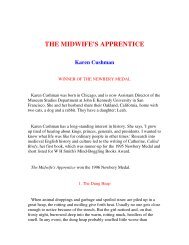

- Page 243 and 244: 7.5J STATE CONTROL 217 regulations,

- Page 245: 7.5] REGISTRATION OF RESOURCES 219

- Page 249 and 250: 7.6] DEPRECIATION OF CURRENCY 223 p

- Page 251 and 252: 7..6J APPORTIONMENT OF LAND 225 feu

- Page 253 and 254: 227 of servitude (as were other bon

- Page 255 and 256: 7.7] FORMATION OF CROWN VILLAGES 22

- Page 257 and 258: 231 Here the rastra private village

- Page 259 and 260: 234 herdsmen-under observation, pro

- Page 261 and 262: 236 READJUSTMENT TO THE NEW LIFE [7

- Page 263 and 264: CHAPTER VIII INTERLUDE OF TRADE AND

- Page 265 and 266: 242 KAMASUTRA OF VATSYAYANA [8.1 im

- Page 267 and 268: 244 TRADE AND PILGRIMAGE [8.1 a spl

- Page 269 and 270: 246 GREEK INVADERS [8.1 Now, with n

- Page 271 and 272: 248 NEW TRIBES AND KINGDOMS [8.1 th

- Page 273 and 274: 250 NEED FOR A CALENDAR [8.2 commen

- Page 275 and 276: 252 MANUSMRTI THEORY OF THE STATE [

- Page 277 and 278: 254 DIFFERENTIAL EXPLOITATION [8.3

- Page 279 and 280: 256 ABSENCE OF UNIFORM LAWS [8.3 si

- Page 281 and 282: 258 GROWTH OF RUSTICITY [8.4 cannot

- Page 283 and 284: 260 NEW PERSONAL GODS [8.4- Bhagabh

- Page 285 and 286: 262 THE SOUTHERN TRACK ROUTE [8.5 a

- Page 287 and 288: 264 MOTHER GODDESSES OF UNIQUE NAME

- Page 289 and 290: 266 BUDDHIST CAVE-COMPLEXES [8.5 bu

- Page 291 and 292: 268 WEALTH OF CAVE FOUNDATIONS [8.5

- Page 293 and 294: 270 TYPES OF DONORS [8.6 settlement

- Page 295 and 296: 272 POWER OF GUILDS [8.6 half a doz

- Page 297 and 298:

274 COCONUTS AND COMMODITY PRODUTTI

- Page 299 and 300:

276 SATAVAHANA TRADE [8.6 and lead;

- Page 301 and 302:

278 ANOMALOUS DEVELOPMENT OF SANSKR

- Page 303 and 304:

280 PRIEST AND PRINCE [S.7 The thre

- Page 305 and 306:

282 GRAMMARIANS ; IDEALISM ; FLORID

- Page 307 and 308:

284 TECHNICAL LITERATURE [8.7 liter

- Page 309 and 310:

286 RELATION TO FEUDALISM [8.8 pros

- Page 311 and 312:

288 ‘ LITTLE CLAY CART ‘ [8.8 f

- Page 313 and 314:

290 KARAGA FESTIVAL [ 8 . & immutab

- Page 315 and 316:

292 INFLUENCE UPON THE VERNACULARS

- Page 317 and 318:

294 NOTES TO CHAPTER VIII original

- Page 319 and 320:

296 THE POLICE GULMA [9.1 intermedi

- Page 321 and 322:

298 UPPER INDIA UNDER THE GUPTAS [9

- Page 323 and 324:

300 TAXES AND TRIBUTES [9.1 This de

- Page 325 and 326:

302 WATERWORKS BHOJA [9.1 trade, po

- Page 327 and 328:

304 RUIN OF PATNA [9.2 of village e

- Page 329 and 330:

306 WARS OF RELIGION [9.2 The chari

- Page 331 and 332:

308 CHINESE ACCOUNTS OF INDIA [9.3

- Page 333 and 334:

310 CHANGES IN FEUDAL STRUCTURE [9.

- Page 335 and 336:

312 TRIBAL ALLIANCES OF THE, GUPTAS

- Page 337 and 338:

314 CASTE AND CLASS ; BUDDHISM [9.4

- Page 339 and 340:

316 ADMINISTRATIVE PRACTICES [9.4 c

- Page 341 and 342:

318 FROM TRIBE TO CASTE (9,4 fighti

- Page 343 and 344:

320 INDIVIDUAL HOLDINGS [9.5 commit

- Page 345 and 346:

322 TRANSFER OF STATE RIGHTS 19.5 t

- Page 347 and 348:

324 MODEL FOR FEUDAL PROPERTY [9.6

- Page 349 and 350:

326 RISE OF MAYtJRASARMAN [9.6 Mayu

- Page 351 and 352:

328 VILLAGE COMMUNITY IN GOA [9.6 n

- Page 353 and 354:

330 LOCAL CONDITIONS IN GOA [9.6 hi

- Page 355 and 356:

332 SHARING OF THE PROFIT [9.6 They

- Page 357 and 358:

334 AN IMPRESSIVE MONUMENT [9.7 tho

- Page 359 and 360:

336 THE GOSTHl J PROBLEMS OF TECHNI

- Page 361 and 362:

338 CONTEMPORARY SURVIVALS [9.7 giv

- Page 363 and 364:

340 ARTISANS IN AMARAKO^A [9.7 like

- Page 365 and 366:

342 NOTES TO CHAPTER IX descriptive

- Page 367 and 368:

344 NOTES TO CHAPTER IX which was t

- Page 369 and 370:

Fig. 41. Wet field (paddy-rice) cul

- Page 371 and 372:

Fig. 43. Kitchen-gardening and tool

- Page 373 and 374:

Fig. 45. Village Oil Press. The art

- Page 375 and 376:

Fig. 47. This is not one of the ess

- Page 377 and 378:

354 CONTRAST WITH EUROPEAN FEUDALIS

- Page 379 and 380:

356 STEADY IMPORT OF HORSES [ 10.1

- Page 381 and 382:

358 INEVITABILITY OF INVASION [10.1

- Page 383 and 384:

360 SUPERIORITY OF FOREIGN SHIPPING

- Page 385 and 386:

362 NECESSITY FOR TRADING BARONS [1

- Page 387 and 388:

364 DEVELOPMENT OF KASMIR 10.2 They

- Page 389 and 390:

366 ECONOMICS OF ICOCLASM [10.2 in

- Page 391 and 392:

368 STRUCTURE OF VIJAYNAGAR EMPIRE

- Page 393 and 394:

370 RAJPUT HIERARCHY ; THE MARKET [

- Page 395 and 396:

372 SANSKRIT IN THE XIITH CENTURY [

- Page 397 and 398:

374 ALAUDDIN’S MEASURES [10.4 liv

- Page 399 and 400:

376 PRICE CONTROL AT THE CENTRE [10

- Page 401 and 402:

378 TAXES, WATER-WORKS, SLAVERY [10

- Page 403 and 404:

380 SLAVERY IN THE XIXTH CENTURY [1

- Page 405 and 406:

382 DEVELOPMENT OF FEUDAL TENURE [1

- Page 407 and 408:

384 TAX-COLLECTION AND ARMED FORCES

- Page 409 and 410:

386 EPHEMERAL CITIES [ 10.5 The eph

- Page 411 and 412:

388 LABOURING CLASS POVERTY [10.5 t

- Page 413 and 414:

390 ECONOMIC BASES OF RELIGIOUS TEN

- Page 415 and 416:

392 A BOURGEOIS VIEW [10.6 the very

- Page 417 and 418:

394 TRADING BARONS [10.6 estimated

- Page 419 and 420:

396 PRE-CONDITIONS FOR BOURGEOIS DE

- Page 421 and 422:

398 PAYMENT OF SUPPLIES [10.7 aband

- Page 423 and 424:

400 CRACKS IN THE MILITARY SYSTEM [

- Page 425 and 426:

402 CHEAPER TAX-COLLECTION [10.7 su

- Page 427 and 428:

404 NOTES TO CHAPTER X 2. The quota