2012 COURSE DATES: AUGUST 4 – 17, 2012 - Sirenian International

2012 COURSE DATES: AUGUST 4 – 17, 2012 - Sirenian International

2012 COURSE DATES: AUGUST 4 – 17, 2012 - Sirenian International

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

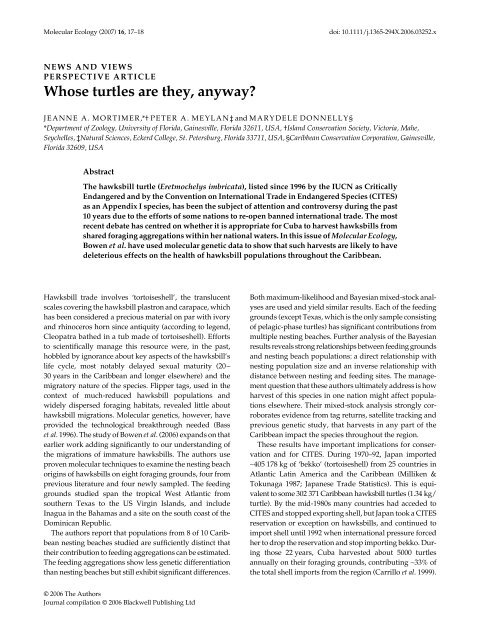

Molecular Ecology (2007) 16,<br />

<strong>17</strong><strong>–</strong>18 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03252.x<br />

Blackwell Publishing Ltd<br />

NEWS AND VIEWS<br />

PERSPECTIVE ARTICLE<br />

Whose turtles are they, anyway?<br />

JEANNE A. MORTIMER, *† PETER A. MEYLAN‡<br />

and MARYDELE DONNELLY§<br />

* Department of Zoology, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611, USA, † Island Conservation Society, Victoria, Mahe,<br />

Seychelles, ‡ Natural Sciences, Eckerd College, St. Petersburg, Florida 33711, USA, § Caribbean Conservation Corporation, Gainesville,<br />

Florida 32609, USA<br />

Abstract<br />

The hawksbill turtle ( Eretmochelys imbricata),<br />

listed since 1996 by the IUCN as Critically<br />

Endangered and by the Convention on <strong>International</strong> Trade in Endangered Species (CITES)<br />

as an Appendix I species, has been the subject of attention and controversy during the past<br />

10 years due to the efforts of some nations to re-open banned international trade. The most<br />

recent debate has centred on whether it is appropriate for Cuba to harvest hawksbills from<br />

shared foraging aggregations within her national waters. In this issue of Molecular Ecology,<br />

Bowen et al.<br />

have used molecular genetic data to show that such harvests are likely to have<br />

deleterious effects on the health of hawksbill populations throughout the Caribbean.<br />

Hawksbill trade involves ‘tortoiseshell’, the translucent<br />

scales covering the hawksbill plastron and carapace, which<br />

has been considered a precious material on par with ivory<br />

and rhinoceros horn since antiquity (according to legend,<br />

Cleopatra bathed in a tub made of tortoiseshell). Efforts<br />

to scientifically manage this resource were, in the past,<br />

hobbled by ignorance about key aspects of the hawksbill’s<br />

life cycle, most notably delayed sexual maturity (20<strong>–</strong><br />

30 years in the Caribbean and longer elsewhere) and the<br />

migratory nature of the species. Flipper tags, used in the<br />

context of much-reduced hawksbill populations and<br />

widely dispersed foraging habitats, revealed little about<br />

hawksbill migrations. Molecular genetics, however, have<br />

provided the technological breakthrough needed (Bass<br />

et al.<br />

1996). The study of Bowen et al.<br />

(2006) expands on that<br />

earlier work adding significantly to our understanding of<br />

the migrations of immature hawksbills. The authors use<br />

proven molecular techniques to examine the nesting beach<br />

origins of hawksbills on eight foraging grounds, four from<br />

previous literature and four newly sampled. The feeding<br />

grounds studied span the tropical West Atlantic from<br />

southern Texas to the US Virgin Islands, and include<br />

Inagua in the Bahamas and a site on the south coast of the<br />

Dominican Republic.<br />

The authors report that populations from 8 of 10 Caribbean<br />

nesting beaches studied are sufficiently distinct that<br />

their contribution to feeding aggregations can be estimated.<br />

The feeding aggregations show less genetic differentiation<br />

than nesting beaches but still exhibit significant differences.<br />

© 2006 The Authors<br />

Journal compilation © 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd<br />

Both maximum-likelihood and Bayesian mixed-stock analyses<br />

are used and yield similar results. Each of the feeding<br />

grounds (except Texas, which is the only sample consisting<br />

of pelagic-phase turtles) has significant contributions from<br />

multiple nesting beaches. Further analysis of the Bayesian<br />

results reveals strong relationships between feeding grounds<br />

and nesting beach populations: a direct relationship with<br />

nesting population size and an inverse relationship with<br />

distance between nesting and feeding sites. The management<br />

question that these authors ultimately address is how<br />

harvest of this species in one nation might affect populations<br />

elsewhere. Their mixed-stock analysis strongly corroborates<br />

evidence from tag returns, satellite tracking and<br />

previous genetic study, that harvests in any part of the<br />

Caribbean impact the species throughout the region.<br />

These results have important implications for conservation<br />

and for CITES. During 1970<strong>–</strong>92, Japan imported<br />

∼405<br />

<strong>17</strong>8 kg of ‘bekko’ (tortoiseshell) from 25 countries in<br />

Atlantic Latin America and the Caribbean (Milliken &<br />

Tokunaga 1987; Japanese Trade Statistics). This is equivalent<br />

to some 302 371 Caribbean hawksbill turtles (1.34 kg/<br />

turtle). By the mid-1980s many countries had acceded to<br />

CITES and stopped exporting shell, but Japan took a CITES<br />

reservation or exception on hawksbills, and continued to<br />

import shell until 1992 when international pressure forced<br />

her to drop the reservation and stop importing bekko. During<br />

those 22 years, Cuba harvested about 5000 turtles<br />

annually on their foraging grounds, contributing ∼33%<br />

of<br />

the total shell imports from the region (Carrillo et al.<br />

1999).