Keith Vodden Dr. Douglas Smith - Transports Canada

Keith Vodden Dr. Douglas Smith - Transports Canada

Keith Vodden Dr. Douglas Smith - Transports Canada

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Analysis and Estimation of the Social Cost of Motor Vehicle Collisions in Ontario<br />

demand for safety as described in Viscusi and Aldy (2003). The lower bound for the<br />

Activity Day variable and the severe injury variable are calculated in the same way.<br />

The upper bound estimates are based on the models estimated by Gunderson and<br />

Hyatt (2001). Their central point is that earlier estimates of the value of a statistical life<br />

may under-estimate the true value of this variable. The potential bias occurs because<br />

other models fail to account for risk preferences that may vary with income and do not<br />

control for selection factors based on risk preferences. In the case of the selection issue,<br />

this means that workers with less risk aversion will accept (self-select into) higher risk<br />

jobs and because they are less risk averse will demand a smaller compensating wage<br />

differential for exposure to risk. The smaller compensating wage differential then underestimates<br />

the required compensation of “average” members of the population for<br />

exposure to risk, thereby under-estimating the costs associated with workplace and other<br />

risks including motor vehicle risks.<br />

The value of a statistical life estimated by Gunderson and Hyatt is $12.75 million,<br />

expressed in 1988 dollars. Converting this to 2004 dollars using the wage index<br />

described above gives the value of $19.7 million shown in Exhibit A-16. The Gunderson<br />

and Hyatt models do not compute the Activity Day and Severe Injury variables that we<br />

plan to use in our modeling. Their overall results indicate that their correction factors<br />

would cause the values to increase by a factor of 5. As a result, we use this factor to<br />

calculate the upper bounds for these variables in Exhibit A-17. The final column of<br />

Exhibit A-15 calculates the mean of the upper and lower bound estimates.<br />

2. Discounted Future Earnings (DFE) Estimates<br />

The discounted future earnings approach measures losses in productive activity in<br />

the workplace and in household activity for those affected by motor vehicle collisions.<br />

Losses through three main types of human consequences are measured: fatalities,<br />

permanent disabilities (total and partial), and temporary disabilities and injuries. More<br />

detail on the DFE approach may be found in Appendix A. Estimates are summarized in<br />

Exhibit A-18.<br />

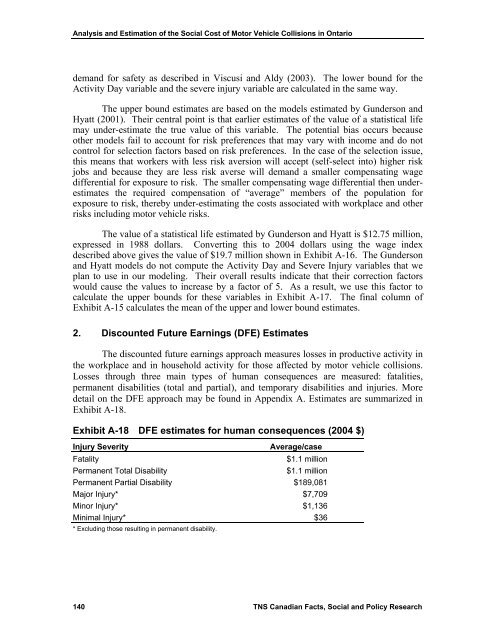

Exhibit A-18 DFE estimates for human consequences (2004 $)<br />

Injury Severity<br />

Average/case<br />

Fatality<br />

$1.1 million<br />

Permanent Total Disability<br />

$1.1 million<br />

Permanent Partial Disability $189,081<br />

Major Injury* $7,709<br />

Minor Injury* $1,136<br />

Minimal Injury* $36<br />

* Excluding those resulting in permanent disability.<br />

140 TNS Canadian Facts, Social and Policy Research