Schwetzingen - Schlösser-Magazin

Schwetzingen - Schlösser-Magazin

Schwetzingen - Schlösser-Magazin

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The interplay between the summer<br />

residence and its landscaped surroundings<br />

at <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> was not, however, confined<br />

– as these concluding observations will<br />

elaborate – to interventions in the form of<br />

those axial paths that wove a tight web across<br />

baronial territory 43 in the Baroque manner,<br />

or of appropriating great swathes of land to<br />

lay out the prince’s garden or imposing an<br />

urban design that would set an enduring<br />

stamp on the spatial order. A very particular<br />

relationship emerged – and has continued<br />

until today – between use of the land and<br />

use of the garden, and then as now it was<br />

characterised by inequalities.<br />

In the 18th century, when large areas of<br />

land were still managed under a three-field<br />

crop rotation system, and forests were used<br />

intensively for the collection of leaf litter,<br />

the landscape was dominated by plant<br />

communities of low productivity. Against<br />

this backdrop, aristocratic gardens played a<br />

role as first movers in cultivating the land<br />

(and not merely as paradise-like islands of<br />

abundance). The creation of kitchen gardens<br />

and the experimental planting of special crops<br />

that took place there was in part inspired by a<br />

desire to improve agrarian production – which<br />

in <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>, naturally, was particularly<br />

the case with asparagus. The “Arborium<br />

Theodoricum” and the model vineyard<br />

there were still tended in the “Protocollum<br />

Commissionale”, despite scant resources,<br />

not least because they served the purpose of<br />

“instruction of their own foresters in types of<br />

wood”. 44<br />

Another example is the expansion of the<br />

orchard on the express orders of Grand<br />

Duke Carl Friedrich, so that “from this rich<br />

store trees may be given to subjects at the<br />

cheapest prices to plant in the streets, the<br />

freemen’s commons and their gardens”. 45 If<br />

the garden in those days was a laboratory of<br />

43 Cornelia Jöchner: Die Ordnung der Dinge: Barockgarten<br />

und politischer Raum. In: ICOMOS, Hefte des Deutschen<br />

Nationalkommitees. München 1997, p. 177f.<br />

44 “Protocollum commissionale” of 30.6.1795 and 9.9.1795. In:<br />

Heber 1986, p. 476.<br />

45 Martin 1933, p. 182; this fruit nursery already contained about<br />

200,000 trees in the early 19 th century.<br />

IV. Palace Gardens: Role and Significance<br />

modernisation, today it harbours relics of an<br />

anthropogenic landscape and has become<br />

a refuge of conservation, including for the<br />

techniques of the gardener’s craft. Meadows<br />

such as the Feldherrnwiese, where hay can be<br />

harvested twice a year, have almost ceased to<br />

exist on in landscapes that have been formed<br />

by human hand.<br />

(Svenja Schrickel/Hartmut Troll)<br />

IV.<br />

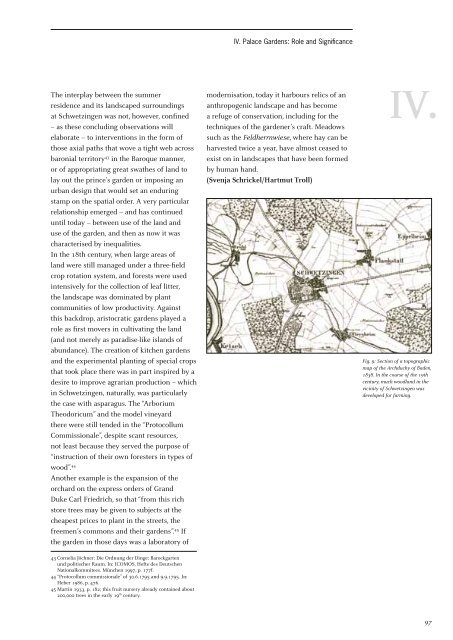

Fig. 9: Section of a topographic<br />

map of the Archduchy of Baden,<br />

1838. In the course of the 19th<br />

century, much woodland in the<br />

vicinity of <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> was<br />

developed for farming.<br />

97