Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations - Kootenay Local Agricultural Society

Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations - Kootenay Local Agricultural Society

Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations - Kootenay Local Agricultural Society

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

118<br />

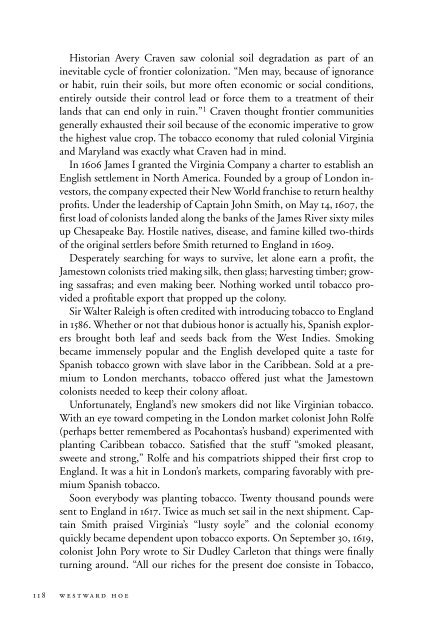

Historian Avery Craven saw colonial soil degradation as part <strong>of</strong> an<br />

inevitable cycle <strong>of</strong> frontier colonization. “Men may, because <strong>of</strong> ignorance<br />

or habit, ruin their soils, but more <strong>of</strong>ten economic or social conditions,<br />

entirely outside their control lead or force them to a treatment <strong>of</strong> their<br />

lands that can end only in ruin.” 1 Craven thought frontier communities<br />

generally exhausted their soil because <strong>of</strong> the economic imperative to grow<br />

the highest value crop. <strong>The</strong> tobacco economy that ruled colonial Virginia<br />

and Maryland was exactly what Craven had in mind.<br />

In 1606 James I granted the Virginia Company a charter to establish an<br />

English settlement in North America. Founded by a group <strong>of</strong> London investors,<br />

the company expected their New World franchise to return healthy<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>its. Under the leadership <strong>of</strong> Captain John Smith, on May 14, 1607, the<br />

first load <strong>of</strong> colonists landed along the banks <strong>of</strong> the James River sixty miles<br />

up Chesapeake Bay. Hostile natives, disease, and famine killed two-thirds<br />

<strong>of</strong> the original settlers before Smith returned to England in 1609.<br />

Desperately searching for ways to survive, let alone earn a pr<strong>of</strong>it, the<br />

Jamestown colonists tried making silk, then glass; harvesting timber; growing<br />

sassafras; and even making beer. Nothing worked until tobacco provided<br />

a pr<strong>of</strong>itable export that propped up the colony.<br />

Sir Walter Raleigh is <strong>of</strong>ten credited with introducing tobacco to England<br />

in 1586. Whether or not that dubious honor is actually his, Spanish explorers<br />

brought both leaf and seeds back from the West Indies. Smoking<br />

became immensely popular and the English developed quite a taste for<br />

Spanish tobacco grown with slave labor in the Caribbean. Sold at a premium<br />

to London merchants, tobacco <strong>of</strong>fered just what the Jamestown<br />

colonists needed to keep their colony afloat.<br />

Unfortunately, England’s new smokers did not like Virginian tobacco.<br />

With an eye toward competing in the London market colonist John Rolfe<br />

(perhaps better remembered as Pocahontas’s husband) experimented with<br />

planting Caribbean tobacco. Satisfied that the stuff “smoked pleasant,<br />

sweete and strong,” Rolfe and his compatriots shipped their first crop to<br />

England. It was a hit in London’s markets, comparing favorably with premium<br />

Spanish tobacco.<br />

Soon everybody was planting tobacco. Twenty thousand pounds were<br />

sent to England in 1617. Twice as much set sail in the next shipment. Captain<br />

Smith praised Virginia’s “lusty soyle” and the colonial economy<br />

quickly became dependent upon tobacco exports. On September 30, 1619,<br />

colonist John Pory wrote to Sir Dudley Carleton that things were finally<br />

turning around. “All our riches for the present doe consiste in Tobacco,<br />

w estward hoe