Bernard Shaw's Remarkable Religion: A Faith That Fits the Facts

Bernard Shaw's Remarkable Religion: A Faith That Fits the Facts

Bernard Shaw's Remarkable Religion: A Faith That Fits the Facts

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

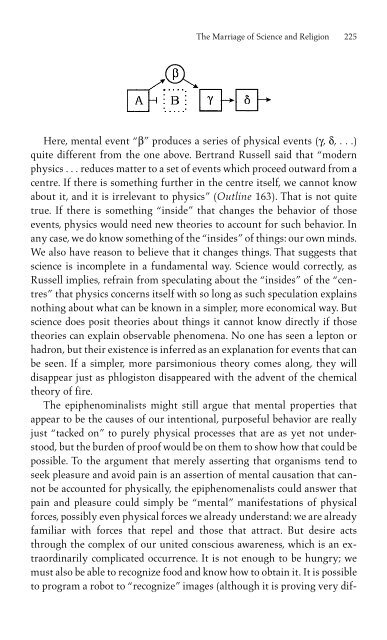

The Marriage of Science and <strong>Religion</strong> 225<br />

Here, mental event “β” produces a series of physical events (γ, δ, . . .)<br />

quite different from <strong>the</strong> one above. Bertrand Russell said that “modern<br />

physics . . . reduces matter to a set of events which proceed outward from a<br />

centre. If <strong>the</strong>re is something fur<strong>the</strong>r in <strong>the</strong> centre itself, we cannot know<br />

about it, and it is irrelevant to physics” (Outline 163). <strong>That</strong> is not quite<br />

true. If <strong>the</strong>re is something “inside” that changes <strong>the</strong> behavior of those<br />

events, physics would need new <strong>the</strong>ories to account for such behavior. In<br />

any case, we do know something of <strong>the</strong> “insides” of things: our own minds.<br />

We also have reason to believe that it changes things. <strong>That</strong> suggests that<br />

science is incomplete in a fundamental way. Science would correctly, as<br />

Russell implies, refrain from speculating about <strong>the</strong> “insides” of <strong>the</strong> “centres”<br />

that physics concerns itself with so long as such speculation explains<br />

nothing about what can be known in a simpler, more economical way. But<br />

science does posit <strong>the</strong>ories about things it cannot know directly if those<br />

<strong>the</strong>ories can explain observable phenomena. No one has seen a lepton or<br />

hadron, but <strong>the</strong>ir existence is inferred as an explanation for events that can<br />

be seen. If a simpler, more parsimonious <strong>the</strong>ory comes along, <strong>the</strong>y will<br />

disappear just as phlogiston disappeared with <strong>the</strong> advent of <strong>the</strong> chemical<br />

<strong>the</strong>ory of fire.<br />

The epiphenominalists might still argue that mental properties that<br />

appear to be <strong>the</strong> causes of our intentional, purposeful behavior are really<br />

just “tacked on” to purely physical processes that are as yet not understood,<br />

but <strong>the</strong> burden of proof would be on <strong>the</strong>m to show how that could be<br />

possible. To <strong>the</strong> argument that merely asserting that organisms tend to<br />

seek pleasure and avoid pain is an assertion of mental causation that cannot<br />

be accounted for physically, <strong>the</strong> epiphenomenalists could answer that<br />

pain and pleasure could simply be “mental” manifestations of physical<br />

forces, possibly even physical forces we already understand: we are already<br />

familiar with forces that repel and those that attract. But desire acts<br />

through <strong>the</strong> complex of our united conscious awareness, which is an extraordinarily<br />

complicated occurrence. It is not enough to be hungry; we<br />

must also be able to recognize food and know how to obtain it. It is possible<br />

to program a robot to “recognize” images (although it is proving very dif-