Authorized Authorized

eERqs

eERqs

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

132 WORLD DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2016<br />

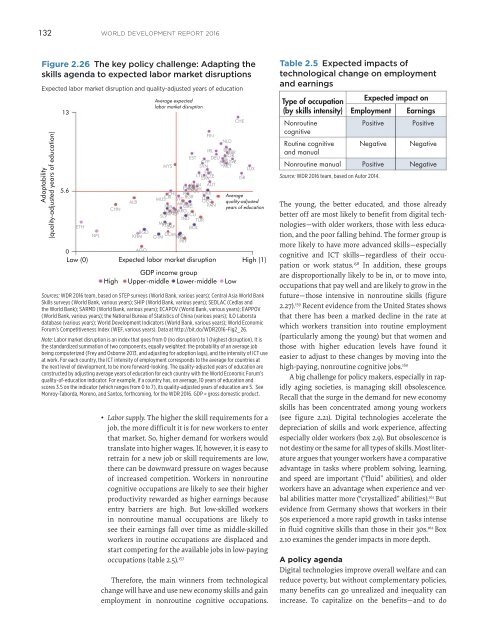

Figure 2.26 The key policy challenge: Adapting the<br />

skills agenda to expected labor market disruptions<br />

Expected labor market disruption and quality-adjusted years of education<br />

Adaptability<br />

(quality-adjusted years of education)<br />

13<br />

Average expected<br />

labor market disruption<br />

FIN<br />

NLD<br />

5.6<br />

IRL BEL<br />

GBR<br />

DEU<br />

NOR<br />

EST<br />

ISL<br />

CYP AUS<br />

DNK<br />

SWE<br />

MYS<br />

SVN MLT<br />

LUX<br />

FRA<br />

LTU<br />

LVA<br />

CZE<br />

ISR<br />

AUT<br />

ESP HRV ROU<br />

HUN<br />

POL<br />

CHL PRT<br />

SVK UKR<br />

CRI<br />

SYC<br />

BGR<br />

Average<br />

MUS<br />

ITA<br />

ALB<br />

GEO<br />

MKD<br />

quality-adjusted<br />

SRB GRC<br />

TJK PAN<br />

CHN<br />

years of education<br />

UZBURYARG<br />

MNG THA<br />

SLV ECU<br />

IND TUR<br />

MEX<br />

ETH<br />

KGZ ZAF BOL<br />

NPL<br />

BGD<br />

KHM<br />

DOM<br />

GTM NIC NGA<br />

PRY<br />

0<br />

AGO<br />

Low (0) Expected labor market disruption High (1)<br />

GDP income group<br />

High Upper-middle Lower-middle Low<br />

Sources: WDR 2016 team, based on STEP surveys (World Bank, various years); Central Asia World Bank<br />

Skills surveys (World Bank, various years); SHIP (World Bank, various years); SEDLAC (Cedlas and<br />

the World Bank); SARMD (World Bank, various years); ECAPOV (World Bank, various years); EAPPOV<br />

(World Bank, various years); the National Bureau of Statistics of China (various years); ILO Laborsta<br />

database (various years); World Development Indicators (World Bank, various years); World Economic<br />

Forum’s Competitiveness Index (WEF, various years). Data at http://bit.do/WDR2016-Fig2_26.<br />

Note: Labor market disruption is an index that goes from 0 (no disruption) to 1 (highest disruption). It is<br />

the standardized summation of two components, equally weighted: the probability of an average job<br />

being computerized (Frey and Osborne 2013, and adjusting for adoption lags), and the intensity of ICT use<br />

at work. For each country, the ICT intensity of employment corresponds to the average for countries at<br />

the next level of development, to be more forward-looking. The quality-adjusted years of education are<br />

constructed by adjusting average years of education for each country with the World Economic Forum’s<br />

quality-of-education indicator. For example, if a country has, on average, 10 years of education and<br />

scores 3.5 on the indicator (which ranges from 0 to 7), its quality-adjusted years of education are 5. See<br />

Monroy-Taborda, Moreno, and Santos, forthcoming, for the WDR 2016. GDP = gross domestic product.<br />

CHE<br />

• Labor supply. The higher the skill requirements for a<br />

job, the more difficult it is for new workers to enter<br />

that market. So, higher demand for workers would<br />

translate into higher wages. If, however, it is easy to<br />

retrain for a new job or skill requirements are low,<br />

there can be downward pressure on wages because<br />

of increased competition. Workers in nonroutine<br />

cognitive occupations are likely to see their higher<br />

productivity rewarded as higher earnings because<br />

entry barriers are high. But low-skilled workers<br />

in nonroutine manual occupations are likely to<br />

see their earnings fall over time as middle-skilled<br />

workers in routine occupations are displaced and<br />

start competing for the available jobs in low-paying<br />

occupations (table 2.5). 157<br />

Therefore, the main winners from technological<br />

change will have and use new economy skills and gain<br />

employment in nonroutine cognitive occupations.<br />

Table 2.5 Expected impacts of<br />

technological change on employment<br />

and earnings<br />

Type of occupation<br />

(by skills intensity)<br />

Nonroutine<br />

cognitive<br />

Routine cognitive<br />

and manual<br />

Expected impact on<br />

Employment Earnings<br />

Positive Positive<br />

Negative<br />

Negative<br />

Nonroutine manual Positive Negative<br />

Source: WDR 2016 team, based on Autor 2014.<br />

The young, the better educated, and those already<br />

better off are most likely to benefit from digital technologies—with<br />

older workers, those with less education,<br />

and the poor falling behind. The former group is<br />

more likely to have more advanced skills—especially<br />

cognitive and ICT skills—regardless of their occupation<br />

or work status. 158 In addition, these groups<br />

are disproportionally likely to be in, or to move into,<br />

occupations that pay well and are likely to grow in the<br />

future—those intensive in nonroutine skills (figure<br />

2.27). 159 Recent evidence from the United States shows<br />

that there has been a marked decline in the rate at<br />

which workers transition into routine employment<br />

(particularly among the young) but that women and<br />

those with higher education levels have found it<br />

easier to adjust to these changes by moving into the<br />

high-paying, nonroutine cognitive jobs. 160<br />

A big challenge for policy makers, especially in rapidly<br />

aging societies, is managing skill obsolescence.<br />

Recall that the surge in the demand for new economy<br />

skills has been concentrated among young workers<br />

(see figure 2.21). Digital technologies accelerate the<br />

depreciation of skills and work experience, affecting<br />

especially older workers (box 2.9). But obsolescence is<br />

not destiny or the same for all types of skills. Most literature<br />

argues that younger workers have a comparative<br />

advantage in tasks where problem solving, learning,<br />

and speed are important (“fluid” abilities), and older<br />

workers have an advantage when experience and verbal<br />

abilities matter more (“crystallized” abilities). 161 But<br />

evidence from Germany shows that workers in their<br />

50s experienced a more rapid growth in tasks intense<br />

in fluid cognitive skills than those in their 30s. 162 Box<br />

2.10 examines the gender impacts in more depth.<br />

A policy agenda<br />

Digital technologies improve overall welfare and can<br />

reduce poverty, but without complementary policies,<br />

many benefits can go unrealized and inequality can<br />

increase. To capitalize on the benefits—and to do