LETTERSTable. Documented cases of pathogenic Oligella ureolytica infection*YearPatientage, yPatientsex Location Culture source Concurrent conditions Urinary disorder Reference†2014 30 M India Blood Metastatic lung Urinary incontinence (3)adenocarcinoma2013 Newborn F Turkey Blood None Maternal urine exposure (4)during delivery?2013 89 M United UrineAdenocarcinoma of High post void residual (5)Statesprostate1996 49 F Canada Neck lymph node Non-Hodgkin lymphoma None (6)1993 40 M United BloodAIDS, sacral ulcer,None (7)Statesdiarrhea*Some published cases that were believed to be contamination or for which the organisms did not fit the laboratory profile of O. ureolytica were excluded.†Antimicrobial drug sensitivity has varied among reports; some resistant organisms have been encountered (3–8).test results were negative. The nonspecific electrocardiogramchanges prompted us to request a transesophagealechocardiogram, but the patient refused. For 10 days, thepatient was given vancomycin (1 g/d), aztreonam (2 g/8h), and metronidazole (500 mg/8 h). Cultures of blood thathad been collected 5 and 8 days after the original culturewere sterile. After 16 days, leukocytosis and fever had resolved,and the patient was discharged to a skilled nursingfacility. Although we found no reports in the literature ofendocarditis caused by O. ureolytica, the patient’s refusalof a transesophageal echocardiogram and the presence ofthe uncommon bacterium led us to empirically continueaztreonam for endocarditis after her discharge.The literature reports 5 cases of pathogenic O. ureolyticainfection (Table). This bacterium has also beenisolated from the respiratory tract of patients with cysticfibrosis (9). A 2-year study conducted in 1983 at ahigh-volume hospital in the United States demonstratedO. ureolytica growth in the urine of 72 patients (8). Ofthese patients, 71 had long-term urinary drainage systemsand 14 had symptomatic urinary tract infections. Many ofthese patients were permanently disabled from spinal cordinjuries (8). This study was the only one we found focusedon O. ureolytica infection in the clinical setting. Wefound no cases in which a patient’s death was attributedto O. ureolytica infection, and all reported cases resolvedwith antimicrobial drug treatment (3–8). The low virulenceof this organism may contribute to the paucity ofrecognized cases.Of the reported cases, all occurred as opportunisticinfections in patients with a source of immunosuppressionsuch as malignancy, HIV, or newborn status. The patientwe reported in this article showed no evidence of malignancyand had no major source of immunosuppressionbesides malnutrition, tobacco use, and advanced age. Thepatient’s wound had been contaminated by urine and feces,which was postulated to be the cause of bacteremiain the 1993 case.Limitations in commonly available laboratory proceduresmake the identification of this bacterium difficult. Theincubation period is long (4 days), and not all laboratoriesincubate cultures for that long, as occurred in the 2013 urinarytract infection case (1,3,5). Also, the identification ofless commonly encountered bacteria is not always pursuedto the genus and species level (2). Furthermore, it is believedthat Oligella spp. can be misidentified as phenotypicallysimilar organisms, such as Bordetella bronchisepticaand Achromobacter spp. (4,10).We believe that many cases of O. ureolytica infectionhave gone unrecognized or were incorrectly identified.Some cases may also have been dismissed as contaminationbecause of laboratorians’ and clinicians’ lack of familiaritywith this bacterium. Our review suggests that advancinglaboratory techniques will lead to more recognizedcases and that further studies are necessary to understandthis bacterium’s clinical significance.AcknowledgmentsSpecial thanks to Rani Bright and the Philadelphia College ofOsteopathic Medicine library staff for their time, effort, andguidance in working on this manuscript.References1. Rossau R, Kersters K, Falsen E, Jantzen E, Segers P, Union A,et al. Oligella, a new genus including Oligella urethralis comb.nov. (formerly Moraxella urethralis) and Oligella ureolyticasp. nov. (formerly CDC group IVe): relationship to Taylorellaequigenitalis and related taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol.1987;37:198–210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/00207713-37-3-1982. Steinberg JP, Burd EM. Other gram-negative and gram-variablebacilli. In: Bennett J, Dolin R, Blaser M, editors. Mandell, Douglas,and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. 8th ed.Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2015. p. 2667–83.3. Baruah FK, Jain M, Lodha M, Grover RK. Blood stream infectionby an emerging pathogen Oligella ureolytica in a cancer patient:case report and review of literature. Indian J Pathol Microbiol.2014;57:141–3. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0377-4929.1309284. Demir T, Celenk N. Bloodstream infection with Oligella ureolyticain a newborn infant: a case report and review of literature.J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8:793–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.3855/jidc.32605. Dabkowski J, Dodds P, Hughes K, Bush M. A persistent, symptomaticurinary tract infection with multiple “negative” urine cultures.Conn Med. 2013;77:27–9.6. Baqi M, Mazzulli T. Oligella infections: case report and review ofthe literature. Can J Infect Dis. 1996;7:377–9.1272 Emerging Infectious Diseases • www.cdc.gov/eid • Vol. 21, No. 7, July 2015

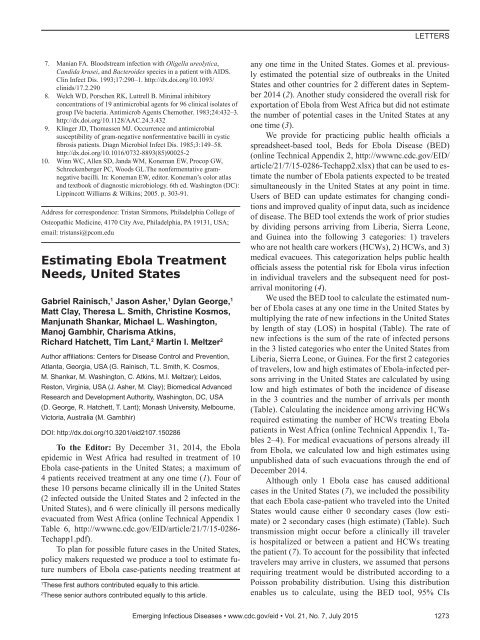

LETTERS7. Manian FA. Bloodstream infection with Oligella ureolytica,Candida krusei, and Bacteroides species in a patient with AIDS.Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:290–1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clinids/17.2.2908. Welch WD, Porschen RK, Luttrell B. Minimal inhibitoryconcentrations of 19 antimicrobial agents for 96 clinical isolates ofgroup IVe bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983;24:432–3.http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.24.3.4329. Klinger JD, Thomassen MJ. Occurrence and antimicrobialsusceptibility of gram-negative nonfermentative bacilli in cysticfibrosis patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1985;3:149–58.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0732-8893(85)90025-210. Winn WC, Allen SD, Janda WM, Koneman EW, Procop GW,Schreckenberger PC, Woods GL.The nonfermentative gramnegativebacilli. In: Koneman EW, editor. Koneman’s color atlasand textbook of diagnostic microbiology. 6th ed. Washington (DC):Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. p. 303-91.Address for correspondence: Tristan Simmons, Philadelphia College ofOsteopathic Medicine, 4170 City Ave, Philadelphia, PA 19131, USA;email: tristansi@pcom.eduEstimating Ebola TreatmentNeeds, United StatesGabriel Rainisch, 1 Jason Asher, 1 Dylan George, 1Matt Clay, Theresa L. Smith, Christine Kosmos,Manjunath Shankar, Michael L. Washington,Manoj Gambhir, Charisma Atkins,Richard Hatchett, Tim Lant, 2 Martin I. Meltzer 2Author affiliations: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,Atlanta, Georgia, USA (G. Rainisch, T.L. Smith, K. Cosmos,M. Shankar, M. Washington, C. Atkins, M.I. Meltzer); Leidos,Reston, Virginia, USA (J. Asher, M. Clay); Biomedical AdvancedResearch and Development Authority, Washington, DC, USA(D. George, R. Hatchett, T. Lant); Monash University, Melbourne,Victoria, Australia (M. Gambhir)DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2107.150286To the Editor: By December 31, 2014, the Ebolaepidemic in West Africa had resulted in treatment of 10Ebola case-patients in the United States; a maximum of4 patients received treatment at any one time (1). Four ofthese 10 persons became clinically ill in the United States(2 infected outside the United States and 2 infected in theUnited States), and 6 were clinically ill persons medicallyevacuated from West Africa (online Technical Appendix 1Table 6, http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/EID/article/21/7/15-0286-Techapp1.<strong>pdf</strong>).To plan for possible future cases in the United States,policy makers requested we produce a tool to estimate futurenumbers of Ebola case-patients needing treatment at1These first authors contributed equally to this article.2These senior authors contributed equally to this article.any one time in the United States. Gomes et al. previouslyestimated the potential size of outbreaks in the UnitedStates and other countries for 2 different dates in September2014 (2). Another study considered the overall risk forexportation of Ebola from West Africa but did not estimatethe number of potential cases in the United States at anyone time (3).We provide for practicing public health officials aspreadsheet-based tool, Beds for Ebola Disease (BED)(online Technical Appendix 2, http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/EID/article/21/7/15-0286-Techapp2.xlsx) that can be used to estimatethe number of Ebola patients expected to be treatedsimultaneously in the United States at any point in time.Users of BED can update estimates for changing conditionsand improved quality of input data, such as incidenceof disease. The BED tool extends the work of prior studiesby dividing persons arriving from Liberia, Sierra Leone,and Guinea into the following 3 categories: 1) travelerswho are not health care workers (HCWs), 2) HCWs, and 3)medical evacuees. This categorization helps public healthofficials assess the potential risk for Ebola virus infectionin individual travelers and the subsequent need for postarrivalmonitoring (4).We used the BED tool to calculate the estimated numberof Ebola cases at any one time in the United States bymultiplying the rate of new infections in the United Statesby length of stay (LOS) in hospital (Table). The rate ofnew infections is the sum of the rate of infected personsin the 3 listed categories who enter the United States fromLiberia, Sierra Leone, or Guinea. For the first 2 categoriesof travelers, low and high estimates of Ebola-infected personsarriving in the United States are calculated by usinglow and high estimates of both the incidence of diseasein the 3 countries and the number of arrivals per month(Table). Calculating the incidence among arriving HCWsrequired estimating the number of HCWs treating Ebolapatients in West Africa (online Technical Appendix 1, Tables2–4). For medical evacuations of persons already illfrom Ebola, we calculated low and high estimates usingunpublished data of such evacuations through the end ofDecember 2014.Although only 1 Ebola case has caused additionalcases in the United States (7), we included the possibilitythat each Ebola case-patient who traveled into the UnitedStates would cause either 0 secondary cases (low estimate)or 2 secondary cases (high estimate) (Table). Suchtransmission might occur before a clinically ill traveleris hospitalized or between a patient and HCWs treatingthe patient (7). To account for the possibility that infectedtravelers may arrive in clusters, we assumed that personsrequiring treatment would be distributed according to aPoisson probability distribution. Using this distributionenables us to calculate, using the BED tool, 95% CIsEmerging Infectious Diseases • www.cdc.gov/eid • Vol. 21, No. 7, July 2015 1273

- Page 3 and 4:

July 2015SynopsisOn the CoverMarian

- Page 5 and 6:

1240 Gastroenteritis OutbreaksCause

- Page 7 and 8:

SYNOPSISDisseminated Infections wit

- Page 9 and 10:

Disseminated Infections with Talaro

- Page 11 and 12:

Disseminated Infections with Talaro

- Page 13 and 14:

Macacine Herpesvirus 1 inLong-Taile

- Page 15 and 16:

Macacine Herpesvirus 1 in Macaques,

- Page 17 and 18:

Macacine Herpesvirus 1 in Macaques,

- Page 19:

Macacine Herpesvirus 1 in Macaques,

- Page 23:

Malaria among Young Infants, Africa

- Page 26 and 27:

RESEARCHFigure 3. Dynamics of 19-kD

- Page 28 and 29:

Transdermal Diagnosis of MalariaUsi

- Page 30 and 31:

RESEARCHFigure 2. A) Acoustic trace

- Page 32 and 33:

RESEARCHof malaria-infected mosquit

- Page 34 and 35:

Lack of Transmission amongClose Con

- Page 36 and 37:

RESEARCH(IFA) and microneutralizati

- Page 38 and 39:

RESEARCHoropharyngeal, and serum sa

- Page 40 and 41:

RESEARCH6. Assiri A, McGeer A, Perl

- Page 42 and 43:

RESEARCHadvanced genomic sequencing

- Page 44 and 45:

RESEARCHTable 2. Next-generation se

- Page 46 and 47:

RESEARCHTable 3. Mutation analysis

- Page 48 and 49:

RESEARCHReferences1. Baize S, Panne

- Page 50 and 51:

Parechovirus Genotype 3 Outbreakamo

- Page 52 and 53:

RESEARCHFigure 1. Venn diagramshowi

- Page 54 and 55:

RESEARCHTable 2. HPeV testing of sp

- Page 56 and 57:

RESEARCHFigure 5. Distribution of h

- Page 58 and 59:

RESEARCHReferences1. Selvarangan R,

- Page 60 and 61:

RESEARCHthe left lobe was sampled b

- Page 62 and 63:

RESEARCHTable 2. Middle East respir

- Page 64 and 65:

RESEARCHseroprevalence in domestic

- Page 66 and 67:

RESEARCHmeasure their current surve

- Page 68 and 69:

RESEARCHTable 2. States with labora

- Page 70 and 71:

RESEARCHFigure 2. Comparison of sur

- Page 72 and 73:

RESEARCH9. Centers for Disease Cont

- Page 74 and 75:

RESEARCHthe analyses. Cases in pers

- Page 76 and 77:

RESEARCHTable 3. Sampling results (

- Page 78 and 79:

RESEARCHpresence of Legionella spp.

- Page 80 and 81:

Seroprevalence for Hepatitis Eand O

- Page 82 and 83:

RESEARCHTable 1. Description of stu

- Page 84 and 85:

RESEARCHTable 3. Crude and adjusted

- Page 86 and 87:

RESEARCHrates by gender or HIV stat

- Page 88 and 89:

RESEARCH25. Taha TE, Kumwenda N, Ka

- Page 90 and 91:

POLICY REVIEWDutch Consensus Guidel

- Page 92 and 93:

POLICY REVIEWTable 3. Comparison of

- Page 94 and 95:

POLICY REVIEW6. Botelho-Nevers E, F

- Page 96 and 97:

DISPATCHESFigure 1. Phylogenetic tr

- Page 98 and 99:

DISPATCHESSevere Pediatric Adenovir

- Page 100 and 101:

DISPATCHESTable 1. Demographics and

- Page 102 and 103:

DISPATCHES13. Kim YJ, Hong JY, Lee

- Page 104 and 105:

DISPATCHESTable. Alignment of resid

- Page 106 and 107:

DISPATCHESFigure 2. Interaction of

- Page 108 and 109:

DISPATCHESSchmallenberg Virus Recur

- Page 110 and 111:

DISPATCHESFigure 2. Detection of Sc

- Page 112 and 113:

DISPATCHESFigure 1. Histopathologic

- Page 114:

DISPATCHESFigure 2. Detection of fo

- Page 117 and 118:

Influenza Virus Strains in the Amer

- Page 119 and 120:

Novel Arenavirus Isolates from Nama

- Page 121 and 122:

Novel Arenaviruses, Southern Africa

- Page 123 and 124:

Readability of Ebola Informationon

- Page 125 and 126:

Readability of Ebola Information on

- Page 127 and 128: Patients under investigation for ME

- Page 129 and 130: Patients under investigation for ME

- Page 131 and 132: Wildlife Reservoir for Hepatitis E

- Page 133 and 134: Asymptomatic Malaria and Other Infe

- Page 135 and 136: Asymptomatic Malaria in Children fr

- Page 137 and 138: Bufavirus in Wild Shrews and Nonhum

- Page 139 and 140: Bufavirus in Wild Shrews and Nonhum

- Page 141 and 142: Range Expansion for Rat Lungworm in

- Page 143 and 144: Slow Clearance of Plasmodium falcip

- Page 145 and 146: Slow Clearance of Plasmodium falcip

- Page 147 and 148: Gastroenteritis Caused by Norovirus

- Page 149 and 150: Ebola Virus Stability on Surfaces a

- Page 151 and 152: Ebola Virus Stability on Surfaces a

- Page 153 and 154: Outbreak of Ciprofloxacin-Resistant

- Page 155 and 156: Outbreak of S. sonnei, South KoreaT

- Page 157 and 158: Rapidly Expanding Range of Highly P

- Page 159 and 160: Cluster of Ebola Virus Disease, Bon

- Page 161 and 162: Cluster of Ebola Virus Disease, Lib

- Page 163 and 164: ANOTHER DIMENSIONThe Past Is Never

- Page 165 and 166: Measles Epidemic, Boston, Massachus

- Page 167 and 168: LETTERSInfluenza A(H5N6)Virus Reass

- Page 169 and 170: LETTERSsystem (8 kb-span paired-end

- Page 171 and 172: LETTERS3. Van Hong N, Amambua-Ngwa

- Page 173 and 174: LETTERSTable. Prevalence of Bartone

- Page 175 and 176: LETTERSavian influenza A(H5N1) viru

- Page 177: LETTERSprovinces and a total of 200

- Page 181 and 182: LETTERSforward projections. N Engl

- Page 183 and 184: LETTERS3. Guindon S, Gascuel OA. Si

- Page 185 and 186: BOOKS AND MEDIAin the port cities o

- Page 187 and 188: ABOUT THE COVERNorth was not intere

- Page 189 and 190: Earning CME CreditTo obtain credit,

- Page 191: Emerging Infectious Diseases is a p