RESEARCHTable 2. Next-generation sequencing of 25 Ebola virus isolates derived from selected patients sampled, Liberia, September 2014–February 2015Sample ID Coverage, %* No. reads Finishing category† GenBank accession no.LIBR0093 99.4 169,000 Coding complete KR006947LIBR0116 97.9 710,168 Coding complete KR006948LIBR10054 98 2,150,725 Coding complete KR006964LIBR0073 98.5 3,351,831 Coding complete KR006944LIBR0503 98.9 3,193,168 Coding complete KR006956LIBR0286 98.3 1,731,953 Coding complete KR006952LIBR0993 96.5 750,000 Standard draft KR006960LIBR0423 97.1 2,676,454 Standard draft KR006954LIBR0333 97.1 1,775,653 Standard draft KR006953LIBR10053 98 1,691,652 Standard draft KR006963LIBR0067 97 2,403,590 Standard draft KR006943LIBR0092 93.9 2,758,142 Standard draft KR006946LIBR0090 93.1 1,422,271 Standard draft KR006945LIBR1413 88.2 2,500,000 Standard draft KR006962LIBR0058 91.4 1,632,978 Standard draft KR006940LIBR0176 89.4 1,907,863 Standard draft KR006951LIBR0168 89.2 1,221,075 Standard draft KR006949LIBR0505 83.8 741,165 Standard draft KR006957LIBR1195 73.1 2,200,773 Standard draft KR006961LIBR0624 68 1,550,511 Standard draft KR006959LIBR0063 69 2,883,384 Standard draft KR006942LIBR0173 72.3 1,456,490 Standard draft KR006950LIBR0059 59.1 851,606 Standard draft KR006941LIBR0605 64.7 1,587,732 Standard draft KR006958LIBR0430 56.2 3,139,009 Standard draft KR006955*Percentage of genome bases (of 18,959 total bases) called in the consensus sequences (requires >3× coverage with base quality >20).†Categories are defined in (19).antibody cocktails targeting EBOV glycoprotein (22–26).These treatments inhibit viral replication by targeting viraltranscripts for degradation (siRNA) or by blocking translation(phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers), or theyacutely neutralize the virus to enable the host to mountan effective immune response (passive immunotherapy).These countermeasures were originally designed specificallyagainst sequences obtained during previous outbreaks(20,27) or were generated against their glycoproteins (e.g.,the monoclonal antibodies [mAbs] were obtained after immunizationwith Ebola virus/H.sapiens-tc/COD/1995/Kikwit-9510621[EBOV/Kik-9510621] [28]).Since the Western Africa outbreak began, at least 33viral mutations have occurred that could affect countermeasures.We previously reported 27 of these mutations(6). Twenty-six (79%) mutations induced nonsynonymouschanges to epitopes recognized by mAbs included in passiveimmunotherapy cocktails. Another 5 (15%) were locatedin published binding regions of siRNA-based therapeuticdrugs. Tekmira has adjusted its siRNAs to account for 4of these 5 changes since its initial publication (29; E.P. Thiet al., unpub. data). The final 2 mutations were located inthe published binding region of primers or probes for quantitativePCR diagnostic tests that have been used duringoutbreak control activities in Liberia: 1 change each in thebinding sites of the Kulesh-TM assay and the Kulesh-MGBassay (9). Nevertheless, reassessment of the assays at US-AMRIID has suggested that the changes will be toleratedwithout loss in sensitivity (data not shown). Changes in allEBOV/Mak sequences are considered “interoutbreak” (n =23); changes observed only in some sequences from WesternAfrica are considered “intraoutbreak” sites (n = 10, EB-OV-WA

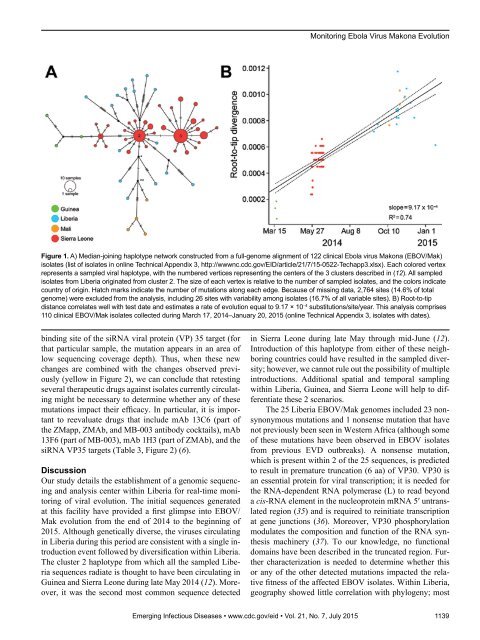

Monitoring Ebola Virus Makona EvolutionFigure 1. A) Median-joining haplotype network constructed from a full-genome alignment of 122 clinical Ebola virus Makona (EBOV/Mak)isolates (list of isolates in online Technical Appendix 3, http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/EID/article/21/7/15-0522-Techapp3.xlsx). Each colored vertexrepresents a sampled viral haplotype, with the numbered vertices representing the centers of the 3 clusters described in (12). All sampledisolates from Liberia originated from cluster 2. The size of each vertex is relative to the number of sampled isolates, and the colors indicatecountry of origin. Hatch marks indicate the number of mutations along each edge. Because of missing data, 2,764 sites (14.6% of totalgenome) were excluded from the analysis, including 26 sites with variability among isolates (16.7% of all variable sites). B) Root-to-tipdistance correlates well with test date and estimates a rate of evolution equal to 9.17 × 10 −4 substitutions/site/year. This analysis comprises110 clinical EBOV/Mak isolates collected during March 17, 2014–January 20, 2015 (online Technical Appendix 3, isolates with dates).binding site of the siRNA viral protein (VP) 35 target (forthat particular sample, the mutation appears in an area oflow sequencing coverage depth). Thus, when these newchanges are combined with the changes observed previously(yellow in Figure 2), we can conclude that retestingseveral therapeutic drugs against isolates currently circulatingmight be necessary to determine whether any of thesemutations impact their efficacy. In particular, it is importantto reevaluate drugs that include mAb 13C6 (part ofthe ZMapp, ZMAb, and MB-003 antibody cocktails), mAb13F6 (part of MB-003), mAb 1H3 (part of ZMAb), and thesiRNA VP35 targets (Table 3, Figure 2) (6).DiscussionOur study details the establishment of a genomic sequencingand analysis center within Liberia for real-time monitoringof viral evolution. The initial sequences generatedat this facility have provided a first glimpse into EBOV/Mak evolution from the end of 2014 to the beginning of2015. Although genetically diverse, the viruses circulatingin Liberia during this period are consistent with a single introductionevent followed by diversification within Liberia.The cluster 2 haplotype from which all the sampled Liberiasequences radiate is thought to have been circulating inGuinea and Sierra Leone during late May 2014 (12). Moreover,it was the second most common sequence detectedin Sierra Leone during late May through mid-June (12).Introduction of this haplotype from either of these neighboringcountries could have resulted in the sampled diversity;however, we cannot rule out the possibility of multipleintroductions. Additional spatial and temporal samplingwithin Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone will help to differentiatethese 2 scenarios.The 25 Liberia EBOV/Mak genomes included 23 nonsynonymousmutations and 1 nonsense mutation that havenot previously been seen in Western Africa (although someof these mutations have been observed in EBOV isolatesfrom previous EVD outbreaks). A nonsense mutation,which is present within 2 of the 25 sequences, is predictedto result in premature truncation (6 aa) of VP30. VP30 isan essential protein for viral transcription; it is needed forthe RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L) to read beyonda cis-RNA element in the nucleoprotein mRNA 5′ untranslatedregion (35) and is required to reinitiate transcriptionat gene junctions (36). Moreover, VP30 phosphorylationmodulates the composition and function of the RNA synthesismachinery (37). To our knowledge, no functionaldomains have been described in the truncated region. Furthercharacterization is needed to determine whether thisor any of the other detected mutations impacted the relativefitness of the affected EBOV isolates. Within Liberia,geography showed little correlation with phylogeny; mostEmerging Infectious Diseases • www.cdc.gov/eid • Vol. 21, No. 7, July 2015 1139

- Page 3 and 4: July 2015SynopsisOn the CoverMarian

- Page 5 and 6: 1240 Gastroenteritis OutbreaksCause

- Page 7 and 8: SYNOPSISDisseminated Infections wit

- Page 9 and 10: Disseminated Infections with Talaro

- Page 11 and 12: Disseminated Infections with Talaro

- Page 13 and 14: Macacine Herpesvirus 1 inLong-Taile

- Page 15 and 16: Macacine Herpesvirus 1 in Macaques,

- Page 17 and 18: Macacine Herpesvirus 1 in Macaques,

- Page 19: Macacine Herpesvirus 1 in Macaques,

- Page 23: Malaria among Young Infants, Africa

- Page 26 and 27: RESEARCHFigure 3. Dynamics of 19-kD

- Page 28 and 29: Transdermal Diagnosis of MalariaUsi

- Page 30 and 31: RESEARCHFigure 2. A) Acoustic trace

- Page 32 and 33: RESEARCHof malaria-infected mosquit

- Page 34 and 35: Lack of Transmission amongClose Con

- Page 36 and 37: RESEARCH(IFA) and microneutralizati

- Page 38 and 39: RESEARCHoropharyngeal, and serum sa

- Page 40 and 41: RESEARCH6. Assiri A, McGeer A, Perl

- Page 42 and 43: RESEARCHadvanced genomic sequencing

- Page 46 and 47: RESEARCHTable 3. Mutation analysis

- Page 48 and 49: RESEARCHReferences1. Baize S, Panne

- Page 50 and 51: Parechovirus Genotype 3 Outbreakamo

- Page 52 and 53: RESEARCHFigure 1. Venn diagramshowi

- Page 54 and 55: RESEARCHTable 2. HPeV testing of sp

- Page 56 and 57: RESEARCHFigure 5. Distribution of h

- Page 58 and 59: RESEARCHReferences1. Selvarangan R,

- Page 60 and 61: RESEARCHthe left lobe was sampled b

- Page 62 and 63: RESEARCHTable 2. Middle East respir

- Page 64 and 65: RESEARCHseroprevalence in domestic

- Page 66 and 67: RESEARCHmeasure their current surve

- Page 68 and 69: RESEARCHTable 2. States with labora

- Page 70 and 71: RESEARCHFigure 2. Comparison of sur

- Page 72 and 73: RESEARCH9. Centers for Disease Cont

- Page 74 and 75: RESEARCHthe analyses. Cases in pers

- Page 76 and 77: RESEARCHTable 3. Sampling results (

- Page 78 and 79: RESEARCHpresence of Legionella spp.

- Page 80 and 81: Seroprevalence for Hepatitis Eand O

- Page 82 and 83: RESEARCHTable 1. Description of stu

- Page 84 and 85: RESEARCHTable 3. Crude and adjusted

- Page 86 and 87: RESEARCHrates by gender or HIV stat

- Page 88 and 89: RESEARCH25. Taha TE, Kumwenda N, Ka

- Page 90 and 91: POLICY REVIEWDutch Consensus Guidel

- Page 92 and 93: POLICY REVIEWTable 3. Comparison of

- Page 94 and 95:

POLICY REVIEW6. Botelho-Nevers E, F

- Page 96 and 97:

DISPATCHESFigure 1. Phylogenetic tr

- Page 98 and 99:

DISPATCHESSevere Pediatric Adenovir

- Page 100 and 101:

DISPATCHESTable 1. Demographics and

- Page 102 and 103:

DISPATCHES13. Kim YJ, Hong JY, Lee

- Page 104 and 105:

DISPATCHESTable. Alignment of resid

- Page 106 and 107:

DISPATCHESFigure 2. Interaction of

- Page 108 and 109:

DISPATCHESSchmallenberg Virus Recur

- Page 110 and 111:

DISPATCHESFigure 2. Detection of Sc

- Page 112 and 113:

DISPATCHESFigure 1. Histopathologic

- Page 114:

DISPATCHESFigure 2. Detection of fo

- Page 117 and 118:

Influenza Virus Strains in the Amer

- Page 119 and 120:

Novel Arenavirus Isolates from Nama

- Page 121 and 122:

Novel Arenaviruses, Southern Africa

- Page 123 and 124:

Readability of Ebola Informationon

- Page 125 and 126:

Readability of Ebola Information on

- Page 127 and 128:

Patients under investigation for ME

- Page 129 and 130:

Patients under investigation for ME

- Page 131 and 132:

Wildlife Reservoir for Hepatitis E

- Page 133 and 134:

Asymptomatic Malaria and Other Infe

- Page 135 and 136:

Asymptomatic Malaria in Children fr

- Page 137 and 138:

Bufavirus in Wild Shrews and Nonhum

- Page 139 and 140:

Bufavirus in Wild Shrews and Nonhum

- Page 141 and 142:

Range Expansion for Rat Lungworm in

- Page 143 and 144:

Slow Clearance of Plasmodium falcip

- Page 145 and 146:

Slow Clearance of Plasmodium falcip

- Page 147 and 148:

Gastroenteritis Caused by Norovirus

- Page 149 and 150:

Ebola Virus Stability on Surfaces a

- Page 151 and 152:

Ebola Virus Stability on Surfaces a

- Page 153 and 154:

Outbreak of Ciprofloxacin-Resistant

- Page 155 and 156:

Outbreak of S. sonnei, South KoreaT

- Page 157 and 158:

Rapidly Expanding Range of Highly P

- Page 159 and 160:

Cluster of Ebola Virus Disease, Bon

- Page 161 and 162:

Cluster of Ebola Virus Disease, Lib

- Page 163 and 164:

ANOTHER DIMENSIONThe Past Is Never

- Page 165 and 166:

Measles Epidemic, Boston, Massachus

- Page 167 and 168:

LETTERSInfluenza A(H5N6)Virus Reass

- Page 169 and 170:

LETTERSsystem (8 kb-span paired-end

- Page 171 and 172:

LETTERS3. Van Hong N, Amambua-Ngwa

- Page 173 and 174:

LETTERSTable. Prevalence of Bartone

- Page 175 and 176:

LETTERSavian influenza A(H5N1) viru

- Page 177 and 178:

LETTERSprovinces and a total of 200

- Page 179 and 180:

LETTERS7. Manian FA. Bloodstream in

- Page 181 and 182:

LETTERSforward projections. N Engl

- Page 183 and 184:

LETTERS3. Guindon S, Gascuel OA. Si

- Page 185 and 186:

BOOKS AND MEDIAin the port cities o

- Page 187 and 188:

ABOUT THE COVERNorth was not intere

- Page 189 and 190:

Earning CME CreditTo obtain credit,

- Page 191:

Emerging Infectious Diseases is a p