Santander, February 19th-22nd 2008 - Aranzadi

Santander, February 19th-22nd 2008 - Aranzadi

Santander, February 19th-22nd 2008 - Aranzadi

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

300<br />

ESTER VERDÚN<br />

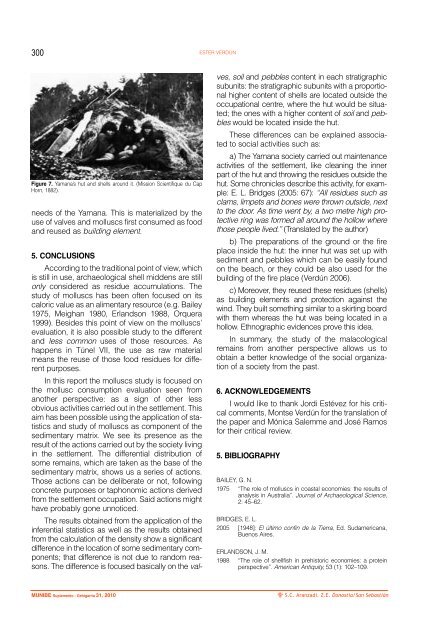

Figure 7. Yamana’s hut and shells around it. (Mission Scientifique du Cap<br />

Horn, 1882).<br />

needs of the Yamana. This is materialized by the<br />

use of valves and molluscs first consumed as food<br />

and reused as building element.<br />

5. CONCLUSIONS<br />

According to the traditional point of view, which<br />

is still in use, archaeological shell middens are still<br />

only considered as residue accumulations. The<br />

study of molluscs has been often focused on its<br />

caloric value as an alimentary resource (e.g. Bailey<br />

1975, Meighan 1980, Erlandson 1988, Orquera<br />

1999). Besides this point of view on the molluscs’<br />

evaluation, it is also possible study to the different<br />

and less common uses of those resources. As<br />

happens in Túnel VII, the use as raw material<br />

means the reuse of those food residues for different<br />

purposes.<br />

In this report the molluscs study is focused on<br />

the mollusc consumption evaluation seen from<br />

another perspective: as a sign of other less<br />

obvious activities carried out in the settlement. This<br />

aim has been possible using the application of statistics<br />

and study of molluscs as component of the<br />

sedimentary matrix. We see its presence as the<br />

result of the actions carried out by the society living<br />

in the settlement. The differential distribution of<br />

some remains, which are taken as the base of the<br />

sedimentary matrix, shows us a series of actions.<br />

Those actions can be deliberate or not, following<br />

concrete purposes or taphonomic actions derived<br />

from the settlement occupation. Said actions might<br />

have probably gone unnoticed.<br />

The results obtained from the application of the<br />

inferential statistics as well as the results obtained<br />

from the calculation of the density show a significant<br />

difference in the location of some sedimentary components;<br />

that difference is not due to random reasons.<br />

The difference is focused basically on the valves,<br />

soil and pebbles content in each stratigraphic<br />

subunits: the stratigraphic subunits with a proportional<br />

higher content of shells are located outside the<br />

occupational centre, where the hut would be situated;<br />

the ones with a higher content of soil and pebbles<br />

would be located inside the hut.<br />

These differences can be explained associated<br />

to social activities such as:<br />

a) The Yamana society carried out maintenance<br />

activities of the settlement, like cleaning the inner<br />

part of the hut and throwing the residues outside the<br />

hut. Some chronicles describe this activity, for example:<br />

E. L. Bridges (2005: 67): “All residues such as<br />

clams, limpets and bones were thrown outside, next<br />

to the door. As time went by, a two metre high protective<br />

ring was formed all around the hollow where<br />

those people lived.” (Translated by the author)<br />

b) The preparations of the ground or the fire<br />

place inside the hut: the inner hut was set up with<br />

sediment and pebbles which can be easily found<br />

on the beach, or they could be also used for the<br />

building of the fire place (Verdún 2006).<br />

c) Moreover, they reused these residues (shells)<br />

as building elements and protection against the<br />

wind. They built something similar to a skirting board<br />

with them whereas the hut was being located in a<br />

hollow. Ethnographic evidences prove this idea.<br />

In summary, the study of the malacological<br />

remains from another perspective allows us to<br />

obtain a better knowledge of the social organization<br />

of a society from the past.<br />

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

I would like to thank Jordi Estévez for his critical<br />

comments, Montse Verdún for the translation of<br />

the paper and Mónica Salemme and José Ramos<br />

for their critical review.<br />

5. BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

BAILEY, G. N.<br />

1975 “The role of molluscs in coastal economies: the results of<br />

analysis in Australia”. Journal of Archaeological Science,<br />

2: 45–62.<br />

BRIDGES, E. L.<br />

2005 [1948]: El último confín de la Tierra, Ed. Sudamericana,<br />

Buenos Aires.<br />

ERLANDSON, J. M.<br />

1988 “The role of shellfish in prehistoric economies: a protein<br />

perspective”. American Antiquity, 53 (1): 102–109.<br />

MUNIBE Suplemento - Gehigarria 31, 2010<br />

S.C. <strong>Aranzadi</strong>. Z.E. Donostia/San Sebastián