Santander, February 19th-22nd 2008 - Aranzadi

Santander, February 19th-22nd 2008 - Aranzadi

Santander, February 19th-22nd 2008 - Aranzadi

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

96<br />

HALA ALARASHI<br />

Figure 8 Detail of the ventral labral face of the cowrie n°132 showing a thin<br />

crack line (scale bar: ¼ cm).<br />

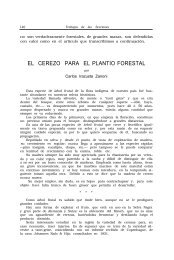

Figure 9 Detail of the dorsal face of the anterior extremity of the cowrie n°33<br />

showing a notch produced by a use wear on the edge of the removed dorsum<br />

(scale bar: ¼ cm).<br />

(ca. 12,500 cal. BP), in the Middle Euphrates, but<br />

only for making holes in Neritidae shells (Maréchal<br />

1991: 608, Maréchal and Alarashi <strong>2008</strong>: 578). The<br />

sawing technique was applied during the PPNB<br />

period in Cyprus to make small holes in the dorsum<br />

part of cowries (Serrand et al. 2005). When<br />

data are available for the same period in the Near<br />

East, grinding technique is mentioned in many<br />

cases for the dorsum removal (Bar-Yosef 2000,<br />

2005, Goring-Morris et al. 1994-95, Reese 1991).<br />

At Tell Aswad, the methods employed to remove<br />

the dorsum part was deduced from the morphological<br />

features of the opening ridge and the<br />

surrounding areas. Only the grinding and the hammering<br />

techniques were clearly evidenced,<br />

although the sawing method or a combination of<br />

different techniques cannot be definitely excluded.<br />

Further analysis could improve these preliminary<br />

observations. According to the experiments I<br />

made on modern specimens, the grinding technique<br />

seems to be more profitable in terms of time<br />

and energy costs than the sawing method.<br />

Hammering could be quite rapid as a technique<br />

but it is more risky.<br />

Apart from the dorsum removal, at least five<br />

cowries were perforated at Tell Aswad. Two<br />

methods were employed to make holes: drilling on<br />

the ventral face and direct or indirect percussion<br />

on the dorsal convex part. Given the low number<br />

of specimens, it cannot be asserted that this<br />

observation reflects a general trend. However, it is<br />

interesting to highlight the originality of the location<br />

of the drilled perforations. As far as I know, holes<br />

made on the ventral face of the cowries were never<br />

documented for the Neolithic times in the region.<br />

Moreover, when perforated cowries are mentioned<br />

in the archaeological literature – exclusively on the<br />

dorsal face – the techniques employed are either<br />

sawing (e.g. Serrand et al. 2005: fig. 5n) or percussion<br />

(e.g. Bienert and Gebel 2004: fig. 13-10).<br />

At Tell Aswad, the ventral perforation concerns not<br />

only cowries without dorsum but also the unique<br />

specimen with dorsum found at the site.<br />

The presence of a series of incisions on two<br />

cowrie beads at Tell Aswad is unexpected. Such a<br />

feature was never described until now for other<br />

Levantine Neolithic sites. In the case of the cowrie<br />

n°33, the distribution of the incisions seems to<br />

have a decorative purpose, that of emphasizing<br />

the natural teeth of the shells. On the other hand,<br />

the incisions made on the columellar part n°143<br />

are relatively rough and not so well organized.<br />

Thus, the ornamental character of the incisions is<br />

not really evident for this object.<br />

Cowrie shells have commonly been used as<br />

symbols related to specific anatomic parts of the<br />

human body such as the eye or the vulva (Gregory<br />

1996, Goren et al. 2001, Kroeber 2001). It is delicate<br />

to address the symbolic, esthetical or cultural<br />

reasons for these incisions, and many possible<br />

answers could be proposed. For instance, might<br />

the cowrie n°33 have artificially represented a<br />

complex natural patterning of the original shell (like<br />

in Erosaria nebrites)? Or simply represented other<br />

radial-structured symbols like sun, mouth or eye?<br />

All that we can say is that, contrary to Jericho<br />

MUNIBE Suplemento - Gehigarria 31, 2010<br />

S.C. <strong>Aranzadi</strong>. Z.E. Donostia/San Sebastián