December 2012 Number 1 - Utah Native Plant Society

December 2012 Number 1 - Utah Native Plant Society

December 2012 Number 1 - Utah Native Plant Society

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Utah</strong> <strong>Native</strong> <strong>Plant</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

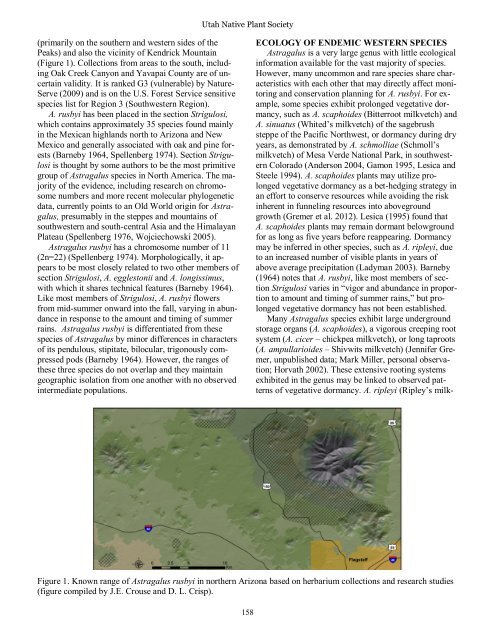

(primarily on the southern and western sides of the<br />

Peaks) and also the vicinity of Kendrick Mountain<br />

(Figure 1). Collections from areas to the south, including<br />

Oak Creek Canyon and Yavapai County are of uncertain<br />

validity. It is ranked G3 (vulnerable) by Nature-<br />

Serve (2009) and is on the U.S. Forest Service sensitive<br />

species list for Region 3 (Southwestern Region).<br />

A. rusbyi has been placed in the section Strigulosi,<br />

which contains approximately 35 species found mainly<br />

in the Mexican highlands north to Arizona and New<br />

Mexico and generally associated with oak and pine forests<br />

(Barneby 1964, Spellenberg 1974). Section Strigulosi<br />

is thought by some authors to be the most primitive<br />

group of Astragalus species in North America. The majority<br />

of the evidence, including research on chromosome<br />

numbers and more recent molecular phylogenetic<br />

data, currently points to an Old World origin for Astragalus,<br />

presumably in the steppes and mountains of<br />

southwestern and south-central Asia and the Himalayan<br />

Plateau (Spellenberg 1976, Wojciechowski 2005).<br />

Astragalus rusbyi has a chromosome number of 11<br />

(2n=22) (Spellenberg 1974). Morphologically, it appears<br />

to be most closely related to two other members of<br />

section Strigulosi, A. egglestonii and A. longissimus,<br />

with which it shares technical features (Barneby 1964).<br />

Like most members of Strigulosi, A. rusbyi flowers<br />

from mid-summer onward into the fall, varying in abundance<br />

in response to the amount and timing of summer<br />

rains. Astragalus rusbyi is differentiated from these<br />

species of Astragalus by minor differences in characters<br />

of its pendulous, stipitate, bilocular, trigonously compressed<br />

pods (Barneby 1964). However, the ranges of<br />

these three species do not overlap and they maintain<br />

geographic isolation from one another with no observed<br />

intermediate populations.<br />

ECOLOGY OF ENDEMIC WESTERN SPECIES<br />

Astragalus is a very large genus with little ecological<br />

information available for the vast majority of species.<br />

However, many uncommon and rare species share characteristics<br />

with each other that may directly affect monitoring<br />

and conservation planning for A. rusbyi. For example,<br />

some species exhibit prolonged vegetative dormancy,<br />

such as A. scaphoides (Bitterroot milkvetch) and<br />

A. sinuatus (Whited’s milkvetch) of the sagebrush<br />

steppe of the Pacific Northwest, or dormancy during dry<br />

years, as demonstrated by A. schmolliae (Schmoll’s<br />

milkvetch) of Mesa Verde National Park, in southwestern<br />

Colorado (Anderson 2004, Gamon 1995, Lesica and<br />

Steele 1994). A. scaphoides plants may utilize prolonged<br />

vegetative dormancy as a bet-hedging strategy in<br />

an effort to conserve resources while avoiding the risk<br />

inherent in funneling resources into aboveground<br />

growth (Gremer et al. <strong>2012</strong>). Lesica (1995) found that<br />

A. scaphoides plants may remain dormant belowground<br />

for as long as five years before reappearing. Dormancy<br />

may be inferred in other species, such as A. ripleyi, due<br />

to an increased number of visible plants in years of<br />

above average precipitation (Ladyman 2003). Barneby<br />

(1964) notes that A. rusbyi, like most members of section<br />

Strigulosi varies in “vigor and abundance in proportion<br />

to amount and timing of summer rains,” but prolonged<br />

vegetative dormancy has not been established.<br />

Many Astragalus species exhibit large underground<br />

storage organs (A. scaphoides), a vigorous creeping root<br />

system (A. cicer – chickpea milkvetch), or long taproots<br />

(A. ampullarioides – Shivwits milkvetch) (Jennifer Gremer,<br />

unpublished data; Mark Miller, personal observation;<br />

Horvath 2002). These extensive rooting systems<br />

exhibited in the genus may be linked to observed patterns<br />

of vegetative dormancy. A. ripleyi (Ripley’s milk-<br />

Figure 1. Known range of Astragalus rusbyi in northern Arizona based on herbarium collections and research studies<br />

(figure compiled by J.E. Crouse and D. L. Crisp).<br />

158